Labor Leaders Struggle to Monitor Prevailing Wage

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — Keeping track of whether those who work in the skilled trades are paid the prevailing wage on government contracts is still done on paper, not computers.

Even if tracking systems were uniform and employed technology, organized labor leaders say it’s nearly impossible to document – and then rectify – situations when prevailing wage laws are violated.And then there’s the matter of municipal income taxes that quite often go unpaid, they claim.

A small number of contractors send their wage records electronically but county and municipal governments print the data and keep the hard copies.

Prevailing wage recordkeeping is “pretty antiquated,” says attorney Tim Jacob, who practices labor law at Manchester, Newman & Bennett, Youngstown. “You have to keep 12 pieces of information and they [the U.S. Department of Labor] don’t specify the format.”

“Prevailing wage records must be kept as paper copies,” says Mahoning County Engineer Patrick Ginnetti.

“Each job has its own specifications,” adds attorney Dennis Haines, who practices labor law at Green Haines Sgambati Co. LPA, Youngstown. “It would be hard to write a [software] program.”

The Trumbull County engineer’s office keeps its prevailing wage paper records up to 10 years.

“Eventually we’ll scan them [to create a database of electronic records],” says the department’s Gary Shaffer. “Most contractors submit weekly, some monthly. Some [records] do come in electronically but we print them out and keep the hard copy.”

Two months ago the city of Youngstown law department acquired new software, called the Empyra system, to monitor contractor compliance with the winning bids they submit, says Kyle Miasek, assistant director of finance.

“It’s how we manage our code enforcement,” says assistant law director Nicole Billec. “It’s a new tool in the future we hope to expand to prevailing wage.”

For now, however, prevailing wage records are kept on the fifth floor of City Hall in the Department of Public Works. The public records had been kept at Youngstown Area Development Corp. on Belmont Avenue until last fall when Rocky DiGennaro, business manager for Local 125 of the Laborers International Union of North America, sought to view them.

When he went to the Department of Public Works, he was informed YADC kept the records. And when he went the YADC office, no one could produce them. It turned out that Yvonne Mathis of the Mathis Group, subcontracted to maintain the records, had them in her car, states the lawsuit Local 125 filed in Mahoning County Common Pleas Court.

While Local 125 has not withdrawn its suit, the records have been returned to City Hall after the city and Local 125 reached an understanding, say Billec and DiGennaro. The contract between Youngstown and YADC had the development agency maintaining the records through March 31.

With such voluminous records, “It does take a long time to find fraud,” the Carpenters’ DiTommaso says. “And when you do find it, it’s hard to find someone who will listen.”

The construction companies and subcontractors who employ skilled tradesmen on public works projects such as schools, roads and bridges use computers to keep track of their payrolls. Some fill out by hand prevailing wage records and submit the paper records to school districts and county, township and municipal governments.

This anomaly makes it harder for union business agents such as Carlton Ingram, Tony DiTommaso and DiGennaro to monitor and ensure that both their members and nonunion workers at the sites are paid what they’re owed.

Ingram is the business agent for Local 66 of the Operating Engineers responsible for Mahoning County. DiTommaso is his counterpart for Local 171 of the Carpenters and Joiners. They and the Laborers local have offices in Boardman.

An often-neglected aspect, all point out, are the income taxes that don’t make it into municipal coffers because of sloppy recordkeeping and the contractors or subcontractors who shortchange their nonunion workers or pay them off the books.

“The city of Youngs-town is short $50,000 to $60,000 because of income taxes not collected [last year],” Ingram says, a figure Crane and DiGennaro agree with. “Very few of the nonunion companies pay city taxes,” Ingram says. “And if they [workers] don’t pay city taxes, they don’t pay the right federal taxes.”

The president of the Western Reserve Building & Construction Trades Council, Don Crane, says nonunion workers sometimes “don’t know they’re working on a prevailing wage project. Even when they find out, they don’t complain because they want to work again.”

None could quantify the taxes lost, the extent of workers not paid prevailing wage or being paid prevailing wage for a documented period but then working off the books after hours or on weekends.

The business agents attend bid openings on public projects where the contractors have agreed that, should they win the contract, “You say you’ll adhere to wages and conditions and sign the documents,” Ingram says. “But in fact, many of them don’t. If you get caught, you pay a penalty.”

All agree that violators see paying a penalty as just a cost of doing business.

“The big dogs,” as Crane calls the major contractors in the Mahoning Valley who employ mostly union labor, are good about honoring the terms of the contracts they win and submitting records as required in full. It’s the nonunion contractors and subcontractors that try to cut corners and give them fits. “You stumble across stuff all the time,” says Local 125’s DiGennaro.

Union business agents rarely visit their offices to inspect prevailing wage documents, the county engineers say. Far more frequent visitors are agents of the Ohio Department of Transportation, the state auditor’s office and the Federal Highway Administration, say Ginnetti and Shaffer.

“These agencies review the project files, usually once a year per project,” Ginnetti says.

The skilled-trades locals are far more likely to visit work sites to ensure the contractors are paying prevailing wage to both their members and nonunion workers, Ingram and DiGennaro say.

“As an agent, you can’t be everywhere,” Ingram explains, which is why he visits government offices to inspect the public records.

“I look at the big projects,” he says. “Sometimes you run out of time. … It would be easier if you could view the records on the Internet. It would save a lot of time.”

At the work sites, the business agents appoint stewards, says the Carpenters’ DiTommaso. “The steward has to be provided training.”

The steward works along side the other tradesmen. “The days of the bull steward are gone,” Crane says. “Our agreements say ‘working foreman.’”

The steward checks the pay stubs of the workers to make sure they match their hours at site and the rates of the positions they filled.

“They’re my eyes and ears. You can’t micromanage every job,” says DiGennaro. If a steward is reluctant to bring a disparity to the contractor or subcontractor’s attention, “I tell them, ‘Make me the heavy.’ Tell the contractor, ‘We want to help you make money, but you’ve got to be fair about it.’ All we want is a level playing field.”

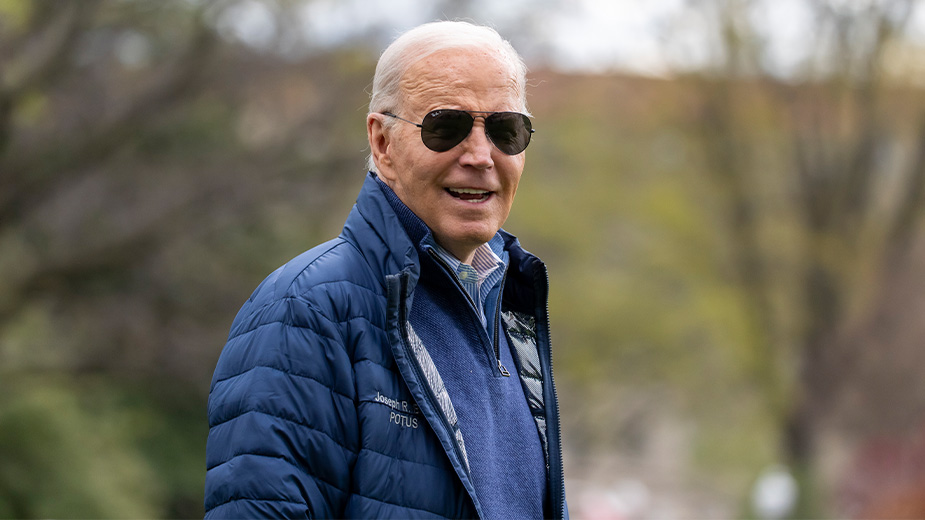

PICTURED: Don Crane is president of the Building Trades Council. Tony DiTommaso is business agent for Local 171 of the Carpenters and Joiners.

VIDEO:

‘3 Minutes With’ Tony DiTommaso, Regional Council of Carpenters

‘3 Minutes With’ Don Crane, Western Reserve Building Trades Council

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.