Linkages Breaks Chain of Addiction, Incarceration

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – The terms “hell on earth” and “living hell” are metaphors only to those not addicted to opiates or alcohol.

His dependency on heroin, says a recovering addict who has re-entered society, “was a hell I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy.”

Withdrawal – weaning himself from illicit drugs – was even worse, says the 31-year-old man who spent three years in prison – he was sentenced to eight – for felony robbery to pay for his habit.

On a morning in late March, the man, whose name The Business Journal agreed not to use, sat with Duane Piccirilli and Brenda Heidinger of the Mahoning County Mental Health & Recovery Board to advocate for IROCS, a new program to reduce recidivism. IROCS is the acronym for Incarceration to Release – Offender Coordinated Services, which has been branded as Linkages.

Piccirilli is executive director of the board, Heidinger associate director.

Participating in Linkages with the mental health board to provide inmates with services are Meridian HealthCare, Turning Point Counseling Center, Catholic Charities Regional Agency, Community Corrections Association Inc. and Flying High Inc. Also supporting Linkages is Mahoning County Sheriff Jerry Greene.

Two annual grants of $150,000 from the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, secured by the mental health board, are paying for Linkages, which allows and encourages the agencies to better coordinate their efforts. Their staffs work with inmates during their incarceration and after they’re released.

Governments create entities, especially publicly funded providers of social services, to alleviate or solve a problem or one aspect of that problem. These entities, in turn, attack their individual piece of the problem, often building silos in the process. They’re aware of related problems but rarely coordinate their efforts with other entities.

Linkages was funded in Mahoning County so entities here can coordinate their efforts to reduce recidivism, Piccirilli says.

While not all addicts have a mental illness and not all mentally ill people self medicate with illicit drugs, the social issues of addiction and mental illness often overlap, Greene notes. Fewer than 10% of the inmates in the county jail, he says, don’t have an issue related to drugs, alcohol or a mental illness. Piccirilli puts that figure at fewer than 30%.

For too long, Greene says, the jail “has been housing addicts and the mentally ill without doing anything” to help them recover. “Mental health just goes so unnoticed. …

“Being the authority over the jail,” the sheriff emphasizes, “our two challenges are addiction and mental illness. … Over a third are on prescription drugs, some [mentally ill] on psychotropic mediation. And that’s just those being treated.”

That’s why he wrote a letter in support of the Linkages grant the mental health and rehabilitation board received.

The mental health board and Meridian HealthCare and Turning Point provide counseling, Catholic Charities housing, Heidinger said.

The 31-year-old recovering addict, who today volunteers to help inmates and the recently released recover and stay sober, dispelled many of the misconceptions the public has about addiction and recovery.

One of the biggest hurdles to seeking help is the stigma of criminality attached to illicit drug use, he said, when it should be viewed as an illness. “There is such a stigma,” he said. Moreover, those closest to an addict want to help but are clueless.

“Your family wants to help you but they don’t know how,” he said of his own experience. “I lived with my mom. It was heartbreaking for her.”

Addiction sneaks up on an abuser, he said. “You begin using to feel good. Before long, you’re using to feel normal.” To satisfy his need for a sense of normality, “I used anything I could get, oxycontin, percocet. … I couldn’t get out of bed in the morning without taking something.”

It was no challenge to score drugs, he said. The only thing the dealer asked in return was money.

To those who didn’t know, he seemed normal. “I played golf. Mentally, I felt I could do anything. I had a motorcycle at the time. In my helmet, I could feel myself nodding off.”

To support his drug abuse, he used the proceeds of his student loans and maxed out his credit cards. He’s repaying the loans and credit card debt, he said.

When he’d exhausted the loans and maxed out his credit cards, he turned to “robbing and stealing in the tri-state area.” He became familiar with Home Depot stores and walked out of them, shopping carts filled with items others asked him to steal. “I went in [to a store] with a list of things every day,” he recalled.

Home Depot security had him and other addicts under surveillance but he could make it to his car and drive off before the guards caught up. Until the last time. He was arrested and held in jail because his “family gave me tough love.” They wouldn’t come up with bail. “I called home but there was no answer. …

“I didn’t come out of my cell the first five days. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t sleep. Crap backs up inside of you” and use of opiates, whether prescribed or illicit, results in constipation.

He informed the sheriff’s deputies of his great discomfort.

“I was in a fog the first 30 days,” the man said. “You probably appear normal” to the deputies as every day they checked his vital signs, “but you’re on your own. You won’t die.”

Awaiting trial, he wasn’t offered counseling and no medical help, “not so much as an aspirin.”

Linkages intends to change this, Piccirilli, Heidinger and Green say, and help felons recover from their addiction so they don’t return to prison. “Recovery is a complete life style change,” Heidinger said.

The 31-year-old, “two years sober next month,” told of his recovery, which included 77 days at Meridian HealthCare. The counseling – he was one of 20 at the time – was “intensive” and centered on ending “my obsession with using.”

During rehabilitation, “I got bored, [an impetus to abuse drugs]. I learned to deal with my thoughts. I did a lot of reading [especially] inspiring stories of people who had recovered from addiction.”

The twice-daily counseling sessions were about “staying away from old friends,” the people he did drugs with, and changing his life. “The only thing you have to change is everything,” the man said.

Today he wakes up at 7 a.m. and begins with a period of prayer or meditation before reporting to his full-time job at 8:30. His workday ends at 5 p.m. when he returns home and takes his dog for a walk.

He still plays golf – his handicap is two – and goes to 12-step meetings twice a week. Once a month he speaks to those in recovery at a Neil Kennedy clinic.

His family never gave up on him, he says. “I spend a lot of time with my family. I have a girlfriend” and to stay away from temptation, “we go to a lot of movies.”

His addiction caused his weight to drop to 150 pounds. With the treatment at Meridian, including good nutrition, he gained 30 pounds during those 77 days. “[Addicts] don’t eat properly,” Heidinger observes. Today the man is back to his pre-abuse weight of 165.

Linkages, still in its infancy, has five in the program, including a 36-year-old woman in the Mahoning County Jail. The Business Journal sat down with her and Chelsea Guerrieri, a substance abuse counselor from Meridian assigned the jail, and Wendy Laurezi, a counselor at Turning Point.

The woman’s account of how she became an addict who turned to crime to support her habit has an all-too-common beginning, prescription medication.

Some candidates for Linkages will be referred by Mahoning County Common Pleas Court judges James Durkin (drug court) and Maureen Sweeney (mental illness court).

The judges will determine the candidates “willingness to change,” Guerreri said, and Meridian helps them gauge that willingness through its staff assessing them.

Staff at Meridian administers shots of Vivitrol, “a medication that blocks the effects of opiates and alcohol,” once every 28 days, Guerreri says.

Abusers range in age from “18 to in their 60s. The ages are all over the place,” Guerreri says. While it’s about half men and half women, “We see a lot more Caucasians than African-Americans.” Most abusers she works with are hooked on “heroin or other opiates, the majority of everybody I have.” And for most, their descent into addiction “begins with prescription painkillers, percocet, but there’s crack cocaine too.”

Laurezi focuses on the inmates with mental illnesses, “a lot of them are bipolar,” she says, “but there’s also PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder], and a lot of childhood trauma. They were physically and sexually abused.”

Anger management is the inmates’ biggest challenge. “We talk about coping skills, positive coping skills,” she says.

The mentally ill must want to recover, just as the addicts want to recover, Laurezi said, before they’re candidates for Linkages. “I know the inmates,” she said. “I’m here three days a week,”

Counseling is the largest component of treatment, Guerreri says. The inmates and those released are “required to go to meetings and join support groups.” In jail, they can progress only as far as the third step in the 12-step programs.

In meeting with the support groups in jail, inmates find “They’re made up of people who have been through what you went through,” she says.

The 36-year-old woman, who has abused cocaine and heroin, has been in jail three times and out twice. She was in this time for violating the terms of her probation. A single mother of four, she stays in touch with her family: “Their father is taking care of two kids, my sister the other two.”

Their support helps. “It’s one thing when you’re holding on,” she says. “It’s something else when someone is holding on with you.”

So many in jail have either exhausted their financial resources or had few to begin with. The 36-year-old woman will have the help of Catholic Charities in having an apartment upon release, paying rent and maintaining it.

“I do have a place to live,” she says. “They’ve made the first month’s deposit.” Through the Western Reserve Transit Authority, Catholic Charities will provide her a bus pass until she gets a new driver’s license. And she will be given a Walmart gift card to add to her meager wardrobe.

The bus pass will allow her to travel to Meridian for counseling after her release – “I’m filing for an early release from July to May,” she said – and she said she wants to return to the jail, but not as an inmate. “I want to come back to help [other] girls. I’m already counseling them.”

In short, “I have a lot of hope,” she says. She will have a sponsor upon release and raises morale among the female inmates. “I’m the jokester,” she says. “Laughter helps a lot. It makes you feel better. You have fun. You pray. You get over it.”

Sheriff Greene is optimistic about Linkages. “It’s our hope that this treatment program will eventually reduce recidivism by stabilizing them while here” he told a reporter, “and find them the resources [for] further rehabilitation or recovery upon release.”

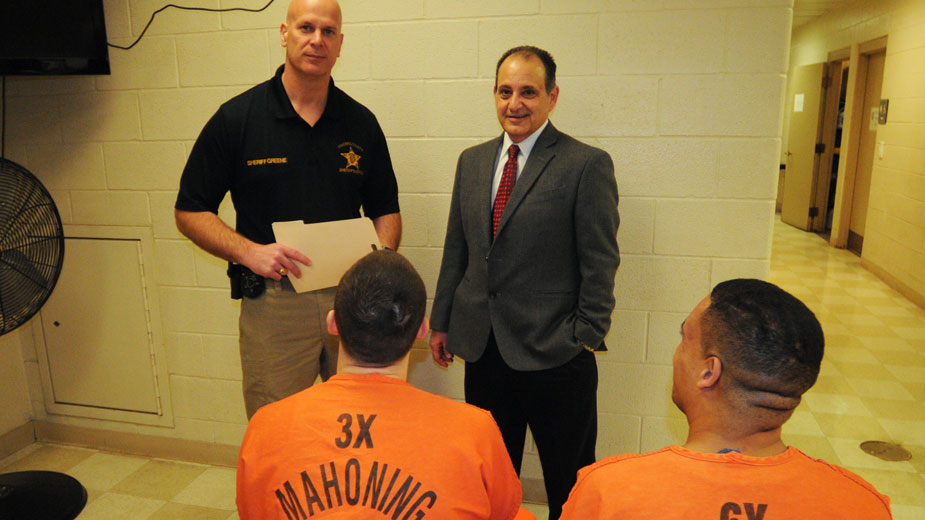

Pictured: Sheriff Jerry Greene and Duane Piccirilli talk to inmates about the Linkages program.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.