‘Lost Youngstown’ Finds City’s Role in Urban History

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – When he was a teenager, Sean Posey’s father took him on a field trip that he could never forget.

This wasn’t your ordinary day excursion to a museum or historic battlefield. This was a trip devoted to exploring the industrial ruins of Youngstown’s storied past – the massive carcasses of steel mills and manufacturing plants that once stretched for miles along the Mahoning River.

“He took me down Poland Avenue and Wilson Avenue in Campbell and I saw these giant husks of mills,” recalls Posey, born in Youngstown but who grew up in the Akron-Canton area. “He talked about working at Republic Steel during the summer, but for people my age, we had never seen buildings that big.”

Now these buildings are empty, choked with weeds and left as ghostly remnants of the region’s rapid industrial decline in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. and Republic Steel Co. once employed 10,000 people along this swath of steelmaking. Today, fewer than 300 work in various capacities in the buildings that still stand.

Still, Posey’s imagination kicked in. What was it like to drive this corridor during the 1950s, a time when these buildings dominated the industrial landscape? How did it look at night as white-hot steel poured from cauldrons within the factories and fire belched from their bellies? What was pedestrian and automobile traffic like as shift changes emptied thousands of workers into the city?

“It was a vivid image to me,” Posey says. “I started getting interested in the city’s history and researching and writing articles about it.” The industrial sector piqued his curiosity about other aspects of life in Youngstown – not only how residents worked, but also how they lived and how they were entertained.

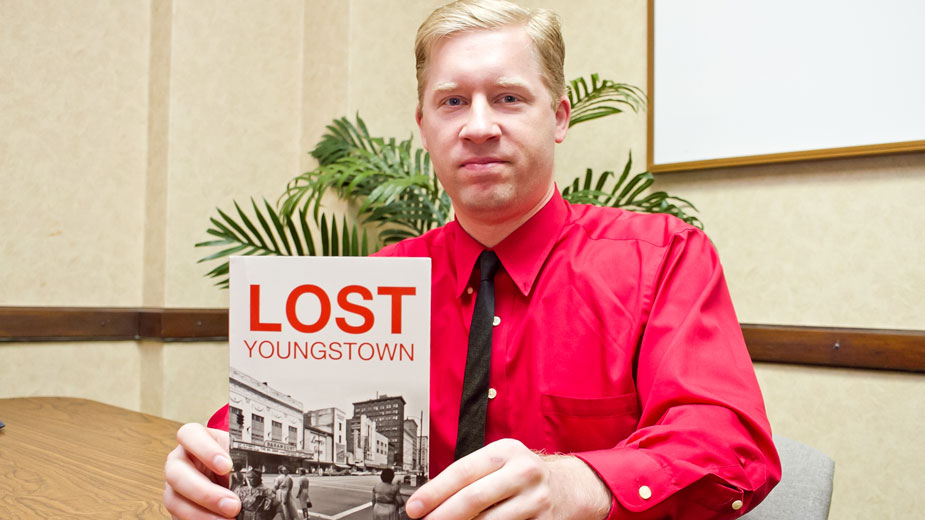

All of this is synthesized in Posey’s new – and first – book, Lost Youngstown, published this month by The History Press. The book brings a fresh perspective to the history of Youngstown from an author who was born after the industrial collapse, who has known only a city dedicated to revitalization and not decline.

The 154-page book is divided into three parts. Part One, “Industrial Colossus,” explores the rise and fall of the well-known Sheet & Tube and the lesser-known saga of The Republic Rubber Co. on the East Side. The second part of the book, “Third Places,” focuses on the cultural landmarks – restaurants, theaters and music halls – while its third section, “Communities of the Past,” revisits life in the Brier Hill/Monkey’s Nest and Smoky Hollow neighborhoods.

“I wanted to give people a look at the city from those three vantage points,” Posey says. “I also wanted to look at places that I thought had not been written about.”

While most are familiar with Black Monday and the economic convulsions that followed the steel shutdowns, few remember the Republic Rubber Co., a smaller concern that nonetheless proved significant in the industrial story of the region and the nation.

Today, incompletely demolished buildings stand at the site along Albert Street. The abandoned area is so inundated with rubble and its buildings so decrepit that about 10 years ago a film crew selected it as the backdrop for a low-budget horror movie set in battle-ravaged Europe during World War II.

“Republic Rubber started out as a small effort to compete with larger companies in Akron,” Posey relates. At its peak in the early 1920s, the company employed about 2,000 and at one time manufactured thousands of products from golf ball cores to some of the first nonskid tires, he notes.

Another product was rubber hosing, Posey says. In 1963, the company, then owned by Lee Tire and Rubber, was sold to competitor Aeroquip Corp., which used the Albert Street plant as its hosing and rubber belt division. Although the Youngstown operation prospered, Aeroquip parent Libby-Owens-Ford targeted the plant for cutbacks. By 1977, only 300 workers remained.

That year, Aeroquip announced it would shut down the plant. “When they closed it, workers and managers got together and reopened it as Republic Hose,” Posey says. “At the time, it was the start of worker-owned cooperatives.”

A similar effort to develop a worker-owned concern at Sheet & Tube failed, but the effort at Republic lasted nearly 10 years. “While it didn’t last very long, it’s become a very important part of what economists are talking about – the spread of worker-owned cooperatives especially in areas where large-scale industries have pulled out,” Posey says.

Part of the book’s appeal is juxtaposing historical images with the author’s own photographs that faithfully illustrate the industrial, neighborhood, and to an extent, cultural, blight associated with each section.

A 2010 photograph of the Paramount Theatre, for example, shows a moment frozen in time as curling strips of film hang loosely from abandoned projectors in a mold-infested projection room. The previous page displays a 2010 interior photo of a once-elaborate theater by then torn to pieces, chunks of plaster littered all over the once-plush seats. Four pages later is an image from 1951 showing a newly renovated interior of the Paramount.

The theater, razed in 2013 because it couldn’t be reclaimed, is now a parking lot.

“I approached photography from an artistic vantage point, getting good composition and exposures,” Posey says. “But, I also wanted to know the history of this place and the purpose of it.”

Another “third places” Posey touches upon is the Uptown district on Market Street. While retail shops and professional offices dominated the downtown from the 1940s through the 1970s, the uptown was the center of the city’s nightlife. Top-notch restaurants such as the Colonial House and entertainment venues such as the Uptown Theater attracted crowds well into the late 1980s. During the 1950s, racketeer Vincent DeNiro’s club, Cicero’s, brought a touch of the notorious to the neighborhood.

DeNiro became the victim of a “Youngstown Tune-Up” in 1961, when a car bomb detonated across the street from his restaurant and killed him instantly.

“When we look beyond the downtown to redevelop other parts of the city, we might want to think about the future of the Uptown,” Posey says, including its adjoining South Side neighborhoods.

Posey points to the potential of one day resurrecting the Uptown Theater. “It’s not a lost cause,” he remarks.

The book examines nightspots and dance clubs that attracted some of the biggest names in the entertainment business during the 1940s through the 1960s. The Nu Elms Ballroom, torn down in the mid 1960s to make way for what today is Kilcawley Center on the campus of Youngstown State University, brought in talents such as Ella Fitzgerald, the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra, and soul artist James Brown.

“My grandparents on my mother’s side met at the Elms,” Posey says. “My grandfather was from Youngstown and my grandmother was from Warren.” Were it not for the Elms, he posits, their paths likely would never have crossed.

Youngstown’s neighborhoods also lend important insights to the character and development of the city, Posey adds. One in particular, the fabled “Monkey’s Nest” area, is completely gone. In its place is the Riverbend Business Park, an industrial sector that includes major manufacturers.

“A lot of younger people would be amazed to think driving down Martin Luther King Boulevard that there were neighborhoods all through there at one time,” Posey says. “No trace of Monkey’s Nest is left.”

The book discusses the ethnic origins of the Monkey’s Nest neighborhood, and the murky origins of its unusual name, Posey notes. “The name is often thought of as pejorative to the people who lived there, “ especially its early 20th century immigrant population of Slovaks – a derivative of “Hunkie’s Nest” – and its later black residents. However, Posey traces the name to at least 1916, when a Vindicator article makes reference to the name of a local tavern in the neighborhood.

“Supposedly, the bar had a live monkey in the window to draw in business,” Posey laughs. “It became popular and became the nickname for the entire area. There’s a story that a car load of monkeys escaped from a rail car and one ended up in the bar.”

Neighborhoods such as Monkey’s Nest and Brier Hill on the North Side, and Smoky Hollow just east of downtown, established ethnic gateway communities for immigrants. Early 19th century coal miners settled in Brier Hill and Monkey’s Nest, while late 19th century immigrants built a strong presence in Smoky Hollow.

Much of the Brier Hill neighborhood was leveled to make way for the Division Street Expressway in the late 1950s, and even more was chipped away with the construction of the 711 Connector about 10 years ago.

“What I learned from this book is – from talking to older people who were here during the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s – it was easy to see why people were so proud of having been from Youngstown.”

So says Phil Kidd, who owns Youngstown Nation, a shop devoted solely to Youngstown-related memorabilia. He says books such as Posey’s present readers with an opportunity to reflect on what is good about this city.

Lost Youngstown is the latest in a string of books published through the History Press and its parent, Arcadia Publishing, Kidd says, and they often sell very well. Thomas Welsh’s Classic Restaurants of Youngstown sold very well, as is Italians of the Mahoning Valley, written by YSU history professors Martha Pallante and Donna DeBlasio.

Moreover, these books help give city planners and neighborhood developers some historical context through economic and cultural insight, especially to those who didn’t live through this era, Kidd says. “I think they’re a necessary component of city planning and community development, especially for a generation that didn’t experience it.”

Posey, who holds a master’s degree in history from YSU, calls Youngstown “the biggest little city on earth.” Its population never exceeded 175,000 but its impact is lasting in the nation’s industrial and urban footprints. “At one time, Youngstown produced more steel per square mile and per capita than any place on earth,” he says.

While much has been written about the steel industry and the region’s affiliation with organized crime, Posey says his objective was to shed light on places, institutions and people in the city’s history that are equally significant in shaping its culture, character and direction. “I wanted to look at places that were important to the city that people hadn’t researched or written a lot about,” he says. “There’s a lot that isn’t well-known that explains to people why Youngstown is such an important city in American urban history.”

WATCH VIDEO:

The Daily BUZZ juxtaposes Youngstown today with how it was in Sean Posey’s book, “Lost Youngstown.”

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.