Open Road for Drug-Free Truck Drivers with Credentials

NEW CASTLE, Pa. — On a frigid bright afternoon, Kinorea Tigri watches as a driver navigates a large flatbed truck backward through an opening of 10 feet bracketed by two orange cones.

Across the yard, others are operating backhoe equipment and practicing maneuvers essential to earning the credentials necessary to join one of the most in-demand careers across the country.

“I hold well over 100 driving jobs at any given week across the board,” says Tigri, facilities manager and director of the New Castle School of Trades’ commercial truck driving program. “It’s unbelievable. I don’t have enough people to fill these posts.”

Demand for truck drivers has exploded over the last five years, especially in the Mahoning and Shenango valleys, Tigri says. While companies that serve the oil and gas industry have scooped up many of these drivers, the huge demand has also created a void for transportation companies that serve other industries. That means more job openings in the general driving field and additional opportunities for those who look to move into these careers.

Even with lower gas prices and a hit in the oil and gas market, companies still crave qualified drivers, Tigri says.

“No one is laying off [in the oil and gas transportation market], but I’m hearing there won’t be any new hiring until April.”

The area’s transportation companies are making a full-court press to find and attract qualified drivers, and often their first choice for potential employees is the trade schools.

“These companies will come into the classrooms and take the opportunity to sell their company to the students,” Tigri adds.

A decade or so ago, companies such as FedEx would never have considered the New Castle School of Trades as fertile ground to recruit drivers, Tigri notes. Now, in a tight labor market, these companies are knocking at the door, pitching the benefits of working for their organizations.

The New Castle, Pa., trade school owns 12 trucks, both heavy equipment and diesel. Its commercial driving director says the driving program is ongoing. At any given time, anywhere between six and 12 students are enrolled.

“I would say demand is high,” she says, pointing to the long waiting list of applicants.

Tigri says her placement rate ranges between 92% and 96%. In many cases, those younger than 21 enter the workforce at a disadvantage because over-the-road employers must pay heftier insurance premiums for these drivers.

“Insurance drives our industry,” she says. However, having a Class B commercial driver’s license is helpful for former students once they turn 21 and look for a job.

According to the U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics, the freight hauling and trucking industries will require another 330,000 new drivers by the year 2020.

The average age of a driver in the industry is 51, and as demand for drivers increases, the supply is likely to decrease.

Meanwhile, trucking companies are pulling out all the stops to attract new drivers in a very tight labor market.

Aim NationaLease, for example, recently launched a special website, JobsAtAim.com, to recruit drivers as well as mechanics and other personnel. The Girard company includes on its site testimonials from some of its employees.

Bill Strimbu, president of Nick Strimbu Inc. in Brookfield, says the job market “has been tight for the last three or four years. Now that the economy is coming back around, it’s putting an even bigger strain on the workforce.”

He emphasizes that Strimbu doesn’t want to hire just drivers, but good drivers who have a spotless record. “They’ve got to be credentialed and have a clean record all the way back to when they were 16,” he says.

Often, the company won’t seriously consider a candidate until he is 23 years old for over-the-road hauling so the driver can meet the guidelines and requirements imposed by several states.

Interest has also declined, Strimbu says, because few are looking for a job that requires extended periods away from home.

“Our traffic lanes are largely along the East Coast up to Maine, as far south as Florida, and west to Chicago and Tennessee,” he says. There are also spot hauling jobs to Oklahoma and Texas. “So, it tightens up.”

Nevertheless, the company has found success in attracting some of the most talented and experienced drivers, Strimbu says.

“Last April, we raised all of our wages considerably. We wanted to put our drivers at the top of the pay scale,” Strimbu says.

This measure, accompanied by the opportunity for drivers to earn bonuses and a modern fleet of trucks, has helped draw some of the best operators to the company, he says.

“These are incentives we use to find and recruit drivers,” Strimbu adds. And the company has an arrangement with a commercial driving school that provides them with a pool of new talent. The challenge with these schools is that some lack the funding to finish the program.

However, should a prospect show potential, Strimbu says that the company would put him through an internal training program.

And, Strimbu says, the company provides the very best Peterbilt trucks on the market. “The oldest truck we have dates to 2012,” he says. “We have all-new equipment,” an important consideration for professional drivers.

So far, the strategy is proving successful.

“At one point, we had a 15% vacancy rate,” Strimbu remarks. “Now, we’ve filled every truck on the fleet.” The company employs 120 drivers and has 10 new trucks on order, he adds.

Moreover, Strimbu’s business is not dedicated to a single industry, so when one sector of the economy is struggling and another is strong, drivers can be cross-trained to keep busy throughout the year. “We have refrigerated, flatbed and specialized divisions. We can put resources to another division when one sector slows down.”

Meanwhile, companies are descending on the trade schools as they look for drivers to replace those nearing retirement age, notes Gary Lopuchovsky, school director at TDDS Technical Institute, in Diamond, Ohio.

“We have twice the number of companies coming in here and getting in front of students,” he says. “We get contacted a couple of times a week from companies – both local and all across the country.”

Only 7% to 10% of applicants to the school are accepted into the program, Lopuchovsky says. The pre-screening involves a drug test that includes monitoring for illegal substances and prescription medication that drivers are prohibited from taking.

All of this, he says, is driven by insurance. “They dictate who can get into the industry,” he explains. “It’s not easy to recruit.”

TDDS advertises heavily on television, targeting those who might recently have lost their jobs and are considering a new career, or young people choosing a job in the industry.

“Our mission is to get them in the industry when they graduate,” Lopuchovsky says. Most opportunities are for over-the-road drivers, positions that generally pay more. “It’s less pay to stay local,” he explains.

Yet some companies are focusing on more regional markets, allowing drivers to make runs that will bring them home on the weekends or a couple of days a week, Lopuchovsky says. “There are just so many jobs out there,” he says.

There is no better time than now for someone to consider becoming a driver, Lopuchovsky notes. Should the economy tighten again, those opportunities could diminish and insurance companies are likely to become even more particular about who they’ll cover as drivers.

“The industry is booming,” he says, “and if you can’t get in now, you probably never will.”

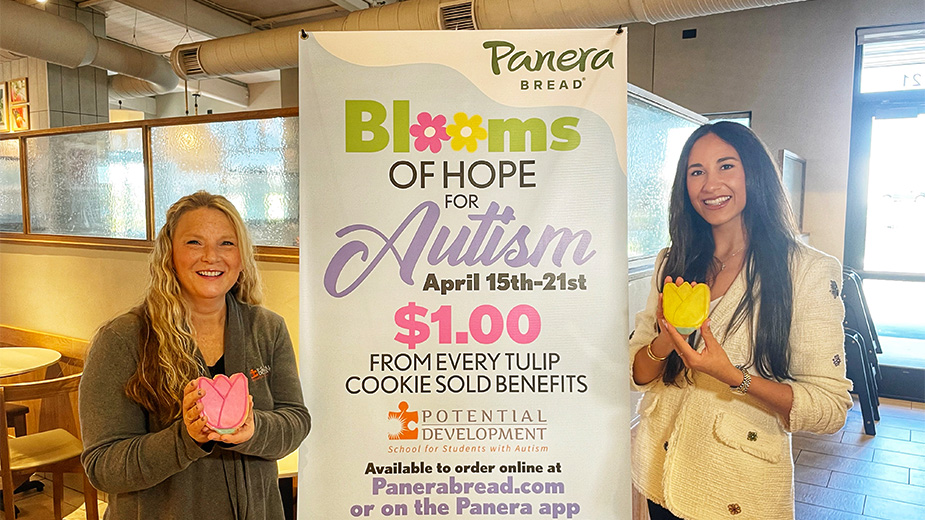

Pictured: Brandon Wagner and Jonathan Romano are students at the New Castle School of Trades’ commercial driving program.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.