Training a Captive Audience for Jobs

GRAFTON,Ohio – In this small town is a job-training site where the residents are learning more than 30 trades or vocations – from maintaining and repairing diesel engines to welding to landscaping to training service dogs that help paraplegics – all paid for by the state.

Among other occupations are producing and editing videos, restaurant operations, cook, butcher, working with sheet metal, painting, plumbing, stitching clothes, CNC machine operator, and heating, ventilation and cooling (HVAC) technician.

The state of Ohio provides the residents, at taxpayer expense, with dormitories, where each has a TV set at the foot of his bed, and dining halls where they eat their meals. If they haven’t graduated from high school, the residents are strongly encouraged to get their GED diplomas. If they are high school graduates, they can take college classes.

This job-training site offers a small number of apprenticeships certified by the U.S. Department of Labor and works closely with nearby universities and community colleges, such as Ashland University. This is the Grafton Correctional Institution, a minimum security prison where the residents are not only learning the skills they need to fill jobs, but how to interview for them, upon their release.

“On the day of their release, they can go to the One-Stop [OhioMeansJobs Center] in their community and shoot their resume to a potential employer,” says Cynthia Williams, a correctional program specialist at Grafton and who holds a baccalaureate in social work.

The Grafton Correctional Institution, 2500 Avon Belden Road in Grafton (Lorain County), focuses on the rehabilitation of its prisoners, all male, and their re-entry into society. “The job placement rate from here is very high,” says Todd Ishee, Northeast regional director of the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction. He declined to elaborate with numbers, explaining unless a former inmate is on parole, there is not tracking mechanism.

Grafton houses 2,040 prisoners; 1,200 are classified as minimum security.

From time to time, job fairs are held at the prison, Williams says. The first was held last summer by “a couple of employers” who believe in its programs.

Ohio spends $27,783.50 per inmate per year, a spokesman for the Department of Rehabilitation and Correction says, or $41.47 per day, which adds up to $1.5 billion a year at the 28 prisons throughout the state system.

One of the most popular programs at Grafton is horticulture because so many men are interested in landscaping. “Part of the appeal is working outside,” says the horticulture instructor, Nate Conrad. “Almost 100% want to start their own business. Fifty percent could.” He advises the men in the program to “Get a job first before you start up. It’s an expensive business.”

Conrad is a member of the Ohio Nursery and Landscape Association, which tests those who want to take part in the one-year course at Grafton. The admissions tests are given three times a year. In addition, those who would enroll must write a 500-word essay on “Why Horticulture?”

On the most recent test, Conrad relates, 14 passed of the 16 who took it.

The well-maintained grounds and manicured lawns around the buildings and within the prison fences attest to the attention to detail the horticulture program promotes.

The program, funded in part by apprenticeship money from the U.S. Department of Labor, consists of eight five-week classes that run 7½ hours weekdays

Conrad mentions the 1,500 flowering plants the Grafton prisoners planted in Columbus last spring at the official residence of the Ohio governor as just one example of the skill and care his students take. The horticulture instructor called their efforts a “community service.”

The prison has four greenhouses on its grounds as well as gardens outdoors that the prisoners tend. “We grow plants for local schools, churches and food banks,” Conrad says. The school groundskeepers, church congregations and food bank staff then landscape the donated plants.

Were it available to public inspection, the program that would warm most visitors’ hearts is the dog-training program, also known as W.A.G.S. 4 Kids, (for Working Animals Giving Service for Kids).

Overseen by Josh Allender, a former inmate at the North Central Correctional Complex who earned his certification there as a dog trainer in 2008, student in this class learn how to work with standard poodles, Labradoodles, Labrador retrievers and Golden Retrievers. They train the dogs to help children ages four to 17 cope with daily life.

Helping him on a warm afternoon are Wendy Nelson Crann, a co-founder of W.A.G.S., and Lisa Schultz, its director of training.

The eight dogs in this class are in the grassy center of 20 students standing in a U-shaped area.

One dog trained here helps Nick Wolczak, a paraplegic, cope with his injuries. Wolczak, confined to a wheelchair, is the student wounded most severely at Chardon High School Feb. 27, 2012. The young man suffered spinal damage and the loss of feeling in his legs.

Other dogs help autistic children and those afflicted with a physically disabling disease. “We do a lot for muscular dystrophy [kids],” Allender states.

The dogs in the year to 1½-year program enter as puppies. “We kennel-train them,” Allender relates, then “We start with the basics – turning on lights and putting away dirty laundry.”

The preferred students “are someone with no dog experience,” he says.

The 20 in the class are learning how to teach the dogs to be alert for, and obey, hand signals “because some kids can’t speak,” Allender explains.

”When we have kids that don’t speak, says Crann, “their dog is their world to them.”

Allender, who was released from North Central in 2011, has stayed with W.A.G.S., training both prisoners and others, because, “It’s always been a good cause. This is the best thing I’ve done with my life. I wanted to do something positive.”

The tailoring workshop, run by Cynthia Williams, has six in its program. They are serving or have less than 24 months until their release and are qualified to work for Goodwill Industries and the Salvation Army upon returning to civilian life.

The prison has its own school where Renee Evett is the principal and Melissa Cheers is the assistant principal. The school has between 20 and 30 tutors, depending on the number of students and how many are taking college courses. Between 60 and 70 are taking a college course at any time.

Those taking a college course are limited to one three-hour class per term. Among the courses offered are psychology, English, economics, contemporary business (basic management) and entrepreneurship, all taught online, says Coleen Wright, the site coordinator for Ashland University.

Certification in the applicable subjects, not a college diploma, is the goal. A high school diploma or GED certificate is the prerequisite to take the classes.

“Fifty percent come in without a GED or high school diploma,” Evett says. The younger prisoners are more enthusiastic about the opportunity to take classes and earn a GED, “the older offenders not so receptive,” she says, especially if they’re eligibility for release in far off.

The school has a library and computer lab where the inmates can do their homework but they can also do it in a break room.

Within the school are classrooms where construction-related trades are taught, including home repair. One classroom is the machine shop where Garth Faldie, a veteran of 30 years in the trade, is the teacher. “Garth has a passion to teach these guys what they need to know,” Ishee says as he introduces him.

“Last year was our first graduating class,” Faldie begins, “and we had a graduate accepted in Cleveland.” The machine precision program, he emphasizes, is like those on the outside and Grafton issues Career Passports to its graduates that certify what they’ve learned and their ability to work on precision machinery.

A third of those released remain on probation, Ishee says, and thus are supervised. The training they receive at Grafton “is the same as they would get at Trumbull Career & Technical Center,” he points out, “or the Mahoning County Career and Technical Center. … These guys deserve a chance. We’re sending these guys out with some pretty good skills.”

Although books on tape (or compact disk) have reduced demand for Braille, Brad Williams teaches it within the school. “Books on tape are not the same as taking a book home, he says. Needed are people who can convert mathematics texts – “transcribing the written word and calculations into Braille,” he explains. “Also musical scores, classical music.”

Those who successfully complete his classes earn a UEB (United English Braille) certificate. “It’s like a court reporter. A smart guy can master this in four months,” Williams says, “but usually it takes six to nine months. You can get a job doing this on the street,” that is, outside the prison, as he rattles off a short litany of such employers.

Welding is a popular subject, says teacher Mike Galo, a welder 35 years who’s taught the subject at Grafton 11 years. He shows off the work his students have completed. Sixteen in his classes have earned various welding certifications such as stick welding and oxyfuel welding. Prisoners can take up to 600 hours of classes.

Their work is used throughout the prison. The students made the trays where their television sets sit atop the feet of their beds, for example.

“The waiting list [to enroll] is very, very long. We can take only 18 or 20 a year,“ the welding instructor says. “I think I’m helping people a little bit.”

Ishee isn’t as reticent. “This is one of the best career welding schools in the [state prison] system,” he declares. “The job placement rate from here is very, very high.”

Being a janitor is more than sweeping floors and emptying wastebaskets with 250 in the apprenticeship program, or more than 10% of the population.

Sixty are in the recycling program where the prisoners learn to quickly separate the trash that consists of metals, plastic and paper. “It’s part of the [Corrections] department’s green initiative,” Ishee says, praising those in the area, who number about 20, as “tireless workers.” Upon release, the men should have little problem finding employment at a recycling center, he says, and “We’ll provide documentation to support” their employment applications outside.

Editing and producing videos is a recent addition to the curriculum at Grafton, and demand is high to participate, says Eric Gardenhire, who oversees the studios. “It’s mushroomed,” he says. “I have 11 inmates working for me. My goal is to equip the inmates with the skill sets they’ll need” upon release. “Some have developed exceptional skills.”

In April, his studio produced 200 hours of finished videos, he reports, including 10 new learning videos.

“A lot of stuff we do is in-house for six prisons in northeast Ohio,” Gardenhire says, including Grafton where the population can, in bed, watch on the Hope Channel many of the videos produced. The channel is available only inside Ohio prisons.

In that “stuff” Gardenhire refers to is how to return to the world outside. “Anatomy of Integration” is one video produced in the prison studio.

“We try to stay sensitive to the needs of our community,” says the teacher who has a baccalaureate in graphic arts and has worked for video studios in Canton. “One program we did was success stories, where [those released] told their stories – the whole story – about getting a job.”

The program is “a shockwave to the prison system in the state of Ohio,” he says, because we’re trying to make them better people, not bitter people. …

”We treat this like a business. We treat them with respect but are not afraid to come down on them if they deserve it.”

In video production, the inmates learn screen-printing and graphics. “A lot of in-house stuff is working with graphics,” Gardenhire elaborates. Inmates can take 8,000 hours [of training] over four years. That includes 2,000 hours of graphics and 3,000 hours of screen-printing. We want to train these men to work so they can work in a professional setting.”

The program impressed Jonathan Demme, who won the Academy Award in 1991 as director of “Silence of the Lambs.” Only the prisoners who work in the Grafton studios can see the graffito he left on one of its walls.

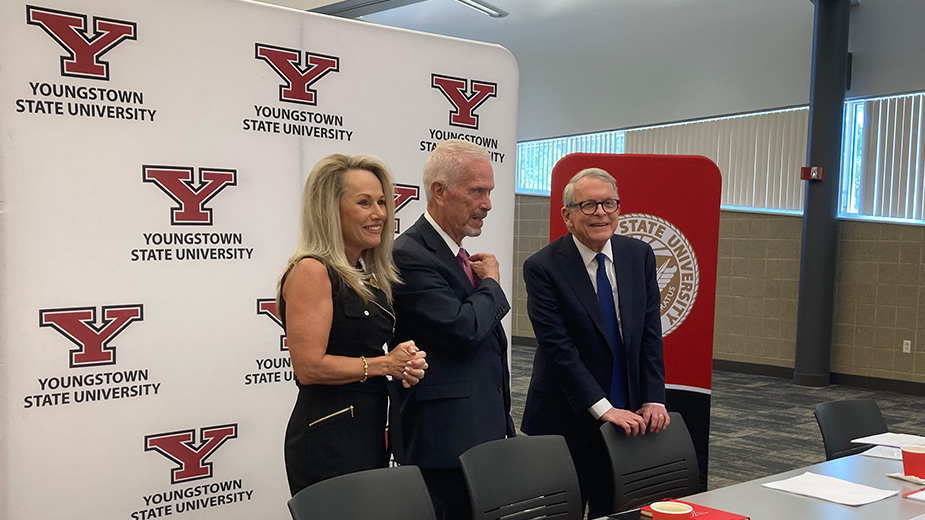

Pictured: Todd Ishee, regional director of the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation, talks with a student in a computer lab.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.