Utica, Marcellus Part of World Energy ‘Revolution’

PITTSBURGH — As a young reporter assigned to cover the energy sector for The Wall Street Journal more than a decade ago, Russell Gold enjoyed a front-row seat to the birth of a revolution that he says today is sweeping the world.

“I saw fracking from its very early stages,” says Gold, senior energy reporter for The Wall Street Journal and author of The Boom: How Fracking Ignited the American Energy Revolution and Changed the World.

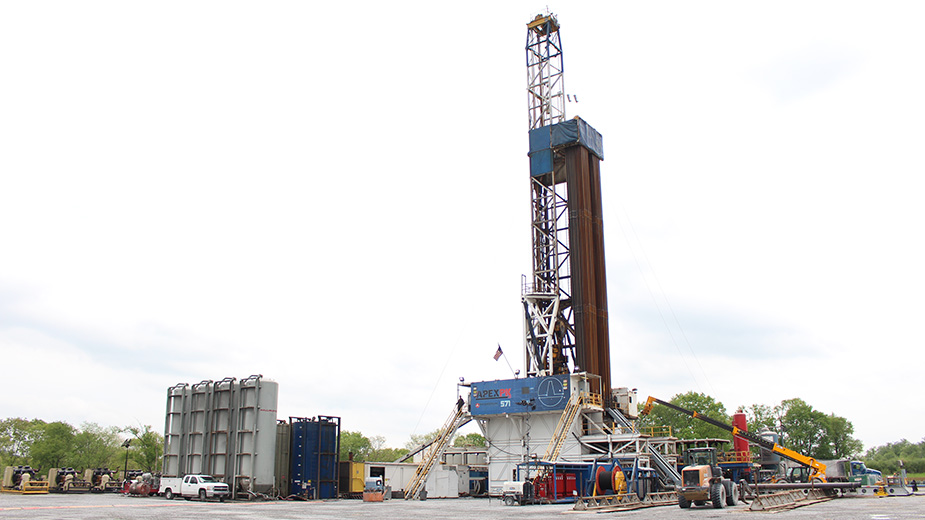

In 2002, companies in Texas exploring for oil and gas in the Barnett shale were still tinkering with the use of hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” Gold recalls. The process involves injecting millions of gallons of water, high volumes of sand and some chemicals into wells in order to fracture tight shale rock and release trapped pockets of oil and gas.

“They didn’t even know what to call it then,” Gold told an audience at Hart Energy’s Marcellus-Utica Midstream Conference Jan. 29. “It was just unconventional gas.”

Since then, hydraulic fracturing — coupled with technological advances in horizontal drilling — has made a profound impact on the energy supply in the United States and on a global scale.

“There’s no question that it’s completely changed the world,” Gold says. “The United States has gone from being an increasing energy importer to suddenly not needing quite as much,” he told The Business Journal following his talk. “The U.S. is producing more oil that it has in 30 or 40 years, and has surprised everyone.”

Natural gas prices are still very low, oil prices began a dramatic tumble this summer, and the amount of natural gas liquids on the market has forced the value of this commodity to historic lows.

“How did we get here?” he asks. “Fracking.”

Gold’s book, published by Simon & Schuster, chronicles the odyssey of hydraulic fracturing from its early incarnations to the recent dash for oil and gas trapped in shale formations beneath North Dakota, Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

“It’s revolutionized the energy picture in the United States, and its slowly being exported to other parts of the world,” Gold says.

Generally, energy markets are reasonably stable when examined over a long period of time, Gold notes. Every so often, however, international tensions or disasters both natural and man-made have led to upheavals, especially in the oil trade.

In 1973, OPEC imposed its crippling boycott on oil exports to the United States in retaliation for the U.S. support of Israel during the Arab-Israeli conflict of that year, Gold relates, leading to the era of “peace, love and gas lines.”

This led the United States to seriously consider alternative sources of energy, and led to more nuclear power plants being commissioned during the mid-1980s. As such, this affected demand for oil, and prices fell.

The energy sector faces a similar upheaval today, Gold says. Yet instead of technology affecting demand as in the case of nuclear power, technology has changed supply.

“We’re clearly in one of those upheavals right now,” he says. At the end of June 2014, oil prices commanded $107 per barrel. Today, it’s hovering around $45 a barrel.

In a five-year period, the U.S. went from producing 5.5 million barrels of oil per day to 9.2 million barrels a day, Gold says. “OPEC is no longer in control of prices,” he adds. Instead, the oil cartel has opted to maintain market share rather than reduce supply from the Middle East, a move that would force higher prices.

Much of this historic shift could be credited to the vast repository of natural gas found in the Marcellus and Utica shale plays. “It’s remarkable what fracking has done — it’s allowed us to overproduce,” Gold says. “It’s an incredible change over a few years ago when we were talking about peak oil — about running out.”

Lower energy prices are in general a benefit to the economy, Gold observes. “It helps industry, consumer confidence and boosts the GDP.”

The obvious downside is that energy companies are forced to curtail production, exploration and investment. This means layoffs and a toll in the oil and gas supply chain. “Clearly, there are areas that will be hit — Pittsburgh, Midland, Texas, North Dakota — they’ll be hurt because they’re focused on bringing oil and gas out of the ground.”

Rig counts in Appalachia are coming down, and it’s clear that shale development cannot sustain the pace it’s set over the last five years. “There’s no way it can continue the way it’s been, so for the next two years there’s going to be leaner times for the industry,” he says.

This isn’t necessarily a bad scenario, he points out, since the objective for the industry is to find a balance between production and pricing so these companies could remain profitable as exploration proceeds in the future.

As for the Utica, Gold says that the shale play was just gaining traction when the glut hit. However, it has all the characteristics of being an important, productive region. Moreover, it’s developing at a slower rate than other shale plays, evidence of measured, healthy growth.

Terry Engelder, professor of geosciences at Penn State University, says the rig count in the Marcellus shale across Pennsylvania is roughly half of what it was in 2011 and 2012.

Part of the reason for this dramatic drop is that energy companies feverishly drilled during the initial phase of the Marcellus rush in order to hold leases, Engelder says. Once that wave subsided, it left many wells drilled but not connected to pipelines, which is what midstream companies are doing now.

About 1,000 wells in the Marcellus are still awaiting pipeline hookups, Engelder says. Once those wells are activated, the Marcellus would take on an entirely new phase of production.

Engelder was among the first to recognize the potential of the Marcellus play, now considered one of the largest natural gas repositories in the world. He was one of the participants in last week’s Hart Energy conference here.

In 2011, just as the play was taking shape, Engelder projected that the formation could yield as much as five trillion cubic feet of gas by the year 2020.

Those projections were well off the mark, he concedes. “It looks like we’re going to hit five trillion by 2016.”

Copyright 2015 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.