Valley’s Italian Heritage Has Roots in ‘Great Coal War’

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – Following the unification of Italian states in the latter half of the 19th century, many peasants faced financial hardships caused by years of war and political turmoil over who would rule what – and how. The process was particularly hard on the southern regions of the country, viewed by their powerful northern counterparts as corrupt and uncivilized.

In the fall of 1872, one of the first great waves of immigrants from southern Italy made their way to the United States, lured by fraudulent reports of easy riches.

In New York City, a flood of destitute Italians began to arrive. In the spring of the following year, telegrams flew between the Mahoning Coal Co. and the Labor Exchange in New York. Soon after, the first contingent of Italians arrived to work in the mines in Coalburg, just outside Hubbard. In May, a second group was sent to the Church Hill Coal Co. mines in Liberty Township. What they didn’t know, however, was that they were brought in as strikebreakers.

And so began the Mahoning Valley’s first settlements of Italian immigrants.

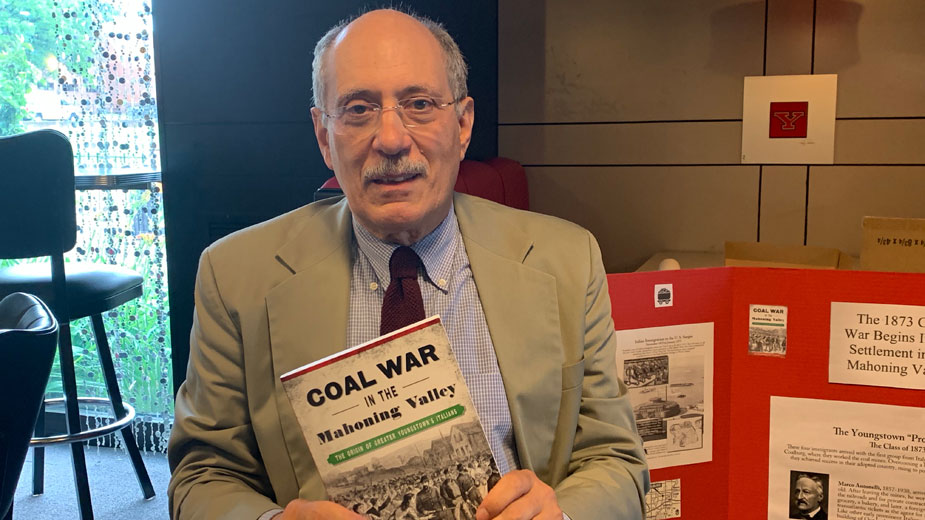

Ben Lariccia, co-author of the upcoming book, “Coal War in the Mahoning Valley: The origin of Greater Youngstown’s Italians,” discussed the precarious circumstances under which the first Italian immigrants arrived here.

Along with co-author Joe Tucciarone, nine years of research and three years of writing was conducted to complete project. The book provides a comprehensive overview of the Great Coal War of 1873, when some 7,500 striking workers clashed with their replacements.

Area industrialists, unwilling to negotiate with their rebellious workers, instead lured scores of Italian immigrants to Hubbard and Liberty Townships, where they were labeled as “strikebreakers” and attacked by striking miners. One death, that of Giovanni Chiesa, was reported, along with several arsons.

Many of these early Italian settlers remained in the area and several went on to become leading citizens of the Mahoning Valley. Lariccia said his co-author discovered in his family history that a great-grandfather had owned a coal mine.

“He was really questioning what did that do with the arrival of the family,” he said. “How is coal connected to his family’s immigration to the United States? He developed a family tree and the more he got into it, [the war] of 1873 came up. He learned later that it was a pivotal event for Italian Americans, and also the Welsh and African-Americans.”

Arriving in increasing numbers since the 1840’s, the Welsh were the most prominent group among the miners. Coalburg, Church Hill and Brier Hill had large settlements. In Wales, they had organized strong trade unions, a tradition they carried to the United States.

On Jan. 1 in 1873, the largely Welsh coal miners’ union went on strike when mine owners demanded a nearly 20% pay cut. Within days, 7,500 men had walked out and almost five months later, the labor conflict ended in defeat for the miners.

Before and after the Civil War, African-Americans had mined coal in the Richmond, Va., area. Predicting that a miners’ strike would occur, Chauncey Andrews used a southern labor agent to hire 100 former slaves and their families to keep his coal pits in Columbiana County open.

In January of 1873, the Virginia men arrived and were given arms to defend themselves. Seeing how the African-Americans worked the Andrews’ pits, coal operator Richard Brown hit upon the idea of using immigrants as strikebreakers.

Lariccia and Tucciarone met up on Facebook and became friends through similar interests in history and being both writers. He said together, they were able to create history that is not known very well through the book.

“[I] want to open this up to many people who don’t know this history,” he said. “We did [this research] together. This really gave a context, it brought up 30 names that people didn’t know were associated [with this history]. It says that the local area was very involved in building great wealth for the United States. The coal from this area went into furnaces that supplied the Union Army.”

President of the Youngstown Torch Club, Tom Welsh, said the club keeps opening up to more outside speakers. To raise the profile of the organization and expand their exposure to what is going on in the community, they thought it would be a good idea to bring in more speakers from the outside.

“Ben is one of those,” he said. “I got to know him personally through a program called Steel City Voices, which is an online archive established by Sherry Linkon. Ben kickstarted the Italian section of that archive because he had so many materials related to the Lariccia family.”

This particular story, Welsh said, is timely because of national discussions over immigration.

“To see how the challenges the Italian-Americans faced is a real eye opener,” he said.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.