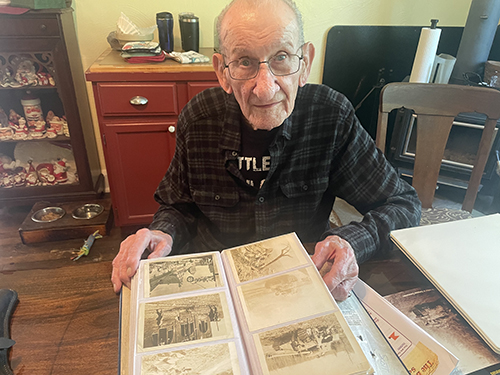

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – Duncan Laverie opens up a thick album filled with faded black and white photographs. Page after page tell a story of war and sacrifice American GIs faced during the final six months of World War II in Europe.

His room in Beaver Township is also filled with memorabilia. A curio frame atop a bookcase holds patches from his unit, the 707th Tank Battalion, a small linen parachute that was once affixed to a German flare, “invasion money,” a tank gunnery manual smeared with what appears to be dried blood, and five battle medallions.

“That’s for the Huertgen Forest there,” the 98-year-old says, tapping on the glass case and pointing to one of the medals. “That was tough. People don’t realize it was also the longest,” he says, shaking his head.

June 6 marked 80 years since the liberation of Western Europe began during World War II. That day, more than 100,000 Allied troops stormed five beaches in Normandy in German-occupied France – an event that in hindsight proved to be the beginning of the end of Hitler’s Third Reich.

Yet the Allied breakout in northern France didn’t occur until the end of July, nearly eight weeks following D-Day. Tenacious fighting among the hedgerows across French terrain confounded American and British forces, stalling their movements. German resistance proved as fierce as ever.

Still, by the end of August 1944, Allied forces had every reason to be optimistic. Paris was liberated on Aug. 25. Victories the following month drove German armies out of the south of France. With dazzling speed, armored divisions raced across France to the German border.

By early September, British regiments had captured the port of Antwerp in Belgium, opening up a critical logistics base to supply liberation forces in the north. Russian armies, meanwhile, began their massive offensive from the east.

For military planners, all that remained was a final thrust into the heart of Germany. Top brass bragged that the war would end by Christmas.

Allied Advance Stalls

Allied armies had indeed moved swiftly – too swiftly. Despite taking Antwerp, momentum had slowed as these forces – continuously harassed by pockets of German resistance – outpaced supply lines. A major setback to take Arnhem in the Netherlands in September 1944 further hindered the advance, as the campaign took heavy casualties and further depleted precious fuel resources.

It was at this juncture that 18-year-old Laverie entered the war in Europe. After basic training at Fort Knox, Kentucky, Laverie landed in Le Havre, France, approximately two months after D-Day. From there, he joined his unit – the 707th Tank Battalion, which was assigned to the 28th Infantry Division.

Trained as a tank gunner, Laverie quickly adapted to the new duty of driver. “My second day there, the lieutenant’s driver was killed by a sniper,” he recalls. “He took me out for a test run – I was 120 pounds.”

Laverie’s slight build made it impossible to drive a medium Sherman tank while seated. “I had to stand up and shift here and there,” he recalls. “It was a circus. But I passed.”

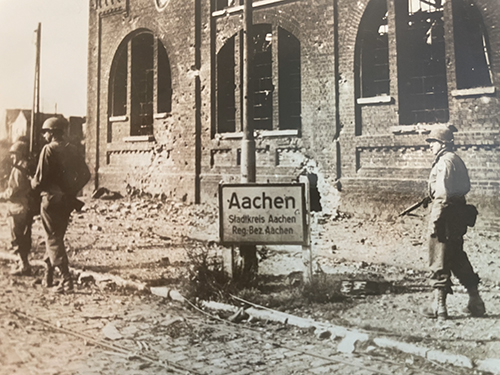

The 28th and 707th moved out in September, experiencing small skirmishes as the units headed toward the German border through Luxembourg and Belgium. Weeks earlier, the upper echelon of the U.S. Army approved a plan to lay a direct assault on the Siegfried Line, a network of concrete German fortifications designed to repel advancing armies. To the north, American forces began the siege of Aachen, which by October became the first major German town to surrender to the allies.

To prevent German reinforcements from defending Aachen, orders were given to attack and take the enemy towns of Vossenack, Kommerscheidt, and the ultimate objective, Schmidt. Holding these positions would pave the way to the Roer River to the east, then across the Rhine and the heart of Germany.

However, military commanders made what would become one of the most disastrous decisions of the war. Orders were given to attack through a patchwork of dense woods, collectively known as the Huertgen Forest. The American 9th Division began its attack Sept. 16 and quickly found it impenetrable.

“I never saw a wood so thick with trees as the Huertgen,” a GI wrote later, quoted in Rick Atkinson’s “Guns at Last Light,” the third installment of the author’s Liberation Trilogy. “It turned out to be the worst place of any.” According to Atkinson, the division by October had taken more than 4,500 casualties to advance just 3,000 yards.

German casualties were also high. Almost half of the 6,500 troops in the 275th Division were captured, killed or wounded in its fight with the 9th, according to Atkinson.

Into the Huertgen Forest

By October, the 28th Division – Laverie was part of A Company of the 707th tank battalion – moved in to relieve the 9th. They walked into a nightmare.

First, the weather turned foul. Cold rain, freezing temperatures and snow complicated the 28th’s movements. Overcast conditions made air support virtually impossible while the forest provided natural camouflage for German positions, making attempts at aerial reconnaissance equally futile. Communications systems were also unreliable.

“Most people misunderstand the Huertgen,” Laverie says. “We were so low on supplies and manpower. That’s why it lasted so long. We were stretched out.”

For two weeks, the 28th – nicknamed the “Bloody Bucket” – was the only division to mount attacks on enemy positions.

Among the most lethal moments in the forest were “treefalls,” Laverie recalls.

Germans would fire artillery shells packed with shrapnel designed to explode on contact with the top of the giant firs that blanketed the forest, Laverie explains. Traditional infantry training taught soldiers to take cover and lay flat during an artillery barrage.

Once one of these shells burst, though, those soldiers taking cover below were sliced to pieces by both shrapnel and shards of wooden splinters, Laverie says. “You were safer standing up instead of laying down or digging a foxhole,” he says. “You’d get stabbed.” In short, the veteran says troops learned to “hug a tree” to save their lives.

Through the first week of fighting, the 28th experienced more than 6,000 casualties, “among the costliest division attacks of the U.S. Army,” according to Atkinson.

Laverie’s company was charged with navigating the Kall Trail, a narrow, forbidding path that stretched from Kommerscheidt to Schmidt. His commander, the respected Lt. Raymond Fleig, led the tanks through, his lead tank hit with a mine and disabled. Using an improvised winch system, the creative Fleig helped guide his tanks across the narrow pass, bracketed by a steep gorge.

Fleig and Company A proved effective, though. In his book “The Battle of Huertgen Forest,” historian Charles MacDonald praised the lieutenant’s leadership in the midst of a campaign that was ill conceived by his superiors from the very start.

“Maneuvering fearlessly from flank to flank, Ray Fleig and his tanks knocked out three of the German tanks,” MacDonald writes. The lieutenant was awarded the Bronze Star with Clusters and a Silver Star for his valor.

After serving in Korea, Fleig relocated to Springfield, Ohio, where he taught high school, retiring in 1984. He died at age 96 in 2015 in Springfield.

Laverie has nothing but praise for Fleig for his superb skills, but doesn’t exonerate the generals – even Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower – who approved such a flawed plan. “The guys in the 707th didn’t like Eisenhower. They blamed that battle on him. He just sent more in there. We didn’t care for him,” he says.

There were, however, moments of humanity during the carnage. As Laverie tells the story, the battle had ravaged both American and German ranks to such a degree that a series of ceasefires were observed to evacuate the dead and treat the wounded.

While several accounts refer to the ceasefires, Laverie says they fail to tell the entire story. A makeshift field hospital established near the Kall River tended to both German and American wounded, staffed with German and American medics.

“For two or three days, we worked together,” Laverie says. “They helped us with our wounded, and we helped them with their wounded.”

Ultimately, the 120,000 soldiers sent into the Huertgen sustained 33,000 casualties. A consensus among military historians placed the blame on poor generalship and planning at the highest levels, noting that the objective all along should have been to secure the major dams along the Roer River. More careful attention would have directed the armies around the Huertgen toward the dams, not through the dense forest.

Historian Stephen Ambrose was especially direct when referring to the first shots of the campaign: “Thus did the Battle of Huertgen get started on the basis of a plan that was grossly, even criminally stupid.”

It wasn’t until February 1945 that the Huertgen would completely fall into Allied hands.

Lost in the Shuffle

Laverie says he’s disappointed that the Huertgen doesn’t get the attention it deserves, underscoring the sacrifice made by his fellow soldiers. It’s often lost in the shuffle between D-Day, Operation Market-Garden and the Battle of the Bulge, Hitler’s last offensive to knock out the Allied advance in December 1944.

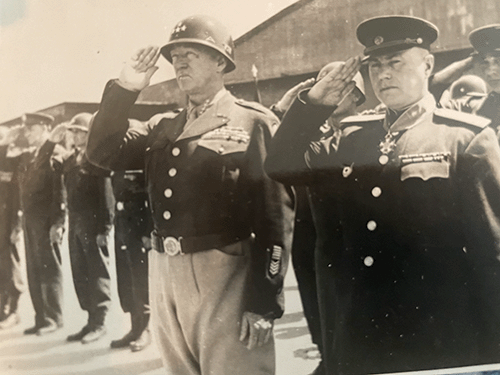

As for Laverie, his unit was sent south from Huertgen to support U.S. troops as they mounted their counterassault on German forces during the Bulge. For a time, the private served with the 3rd Army under George S. Patton.

“I saw him twice,” he recalls. He was present when one of his fellow soldiers snapped a picture of Patton and a Red Army general in Germany as the war in Europe came to a close in 1945. “I was on guard duty that day,” he recalls. At the close of the war, his unit witnessed firsthand the horrors of the Third Reich as they entered the Dachau concentration camp.

On April 6, 1945 – one month before the war in Europe ended – Laverie captured a German SS officer, along with two teenage soldiers riding in the same vehicle.

To this day, he has the officer’s Luger pistol, his Iron Cross decorations, binoculars and Leica camera. “He was a veteran of World War I and World War II,” he recalls.

Laverie found himself near the Czechoslovakian border when news came that Germany had surrendered. After the war, he remained in Germany where he ran an EM, or enlisted men’s, club. He returned home in 1946 after earning the sufficient points needed for discharge.

Laverie then spent most of his career as a machinist at U.S. Steel’s Ohio Works and McDonald plants.

After 80 years, the bitterness of the Huertgen Forest remains, and just two men of A Company are sill alive to tell their stories – stories that Laverie feels have been largely ignored for decades.

“I’m still angry about that,” Laverie reflects. “Was I terrified? Damn right I was.”

Pictured at top: Duncan Laverie of New Springfield participated in the Huertgen Forest campaign in 1944 as a member of the 707th Tank Battalion. A curio case holds patches from Laverie’s unit, the 707th Tank Battalion.