YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – The Youngstown Historical Center of Industry and Labor – commonly known as the Steel Museum – has been a presence in the Mahoning Valley for more than 30 years.

Its creation came in fits and starts, suffering from lack of capitalization over the years (not unlike the industry it memorializes), but ultimately has endured as a fixture of downtown Youngstown’s landscape and as a repository for a major portion of the region’s history.

“A museum preserving the industrial traditions of the Mahoning Valley is an idea apparently destined to become reality,” the lead paragraph in a March 1985 story in the Youngstown Business Journal accurately prophesied.

Legislation sponsored by the late state Sen. Harry Meshel allocated $3.8 million for construction of the industrial museum, which also would serve as an archives and research center. Meshel’s personal history included working in the open hearth of U.S. Steel Corp.’s Ohio Works.

The state historical society – today known as Ohio History Connection – considered launching three museums in the late 1970s but Youngstown’s project was the only one that came to fruition, recalls Donna DiBlasio, today emerita professor of history at Youngstown State University. DiBlasio was hired in 1985 as program supervisor for the museum by the historical society, which was to operate the museum.

“Ours was, of course, going to focus on the iron and steel industry, which makes loads of sense,” she says.

In addition, the society was compiling collections of labor history and artifacts, so that was folded into the museum’s mission as well. That also made sense to DiBlasio.

“If you’re going to focus on the iron and steel industry, you need to focus on labor as well. I mean, the mills don’t run themselves,” she says.

The museum was to be built on a site bounded by Wood, Hazel and Commerce streets in downtown Youngstown. Construction was set to begin in the fall of 1986 and an opening for the museum was planned for fall 1987.

Famed architect Michael Graves served as consulting architect on the project. The design incorporated the look of steel mills from different eras, including a section resembling a smokestack.

According to the late Raymond J. Jaminet, whose Youngstown architectural firm was overseeing the design with Graves, the design was well received by the state historical society and the board of trustees at YSU, which was serving as the conduit for $4.3 million in funding by that point.

“We have drawings in Columbus waiting for state approval,” Jaminet said in April of 1986. “We intend to break ground late in September for the landscaping, and the museum itself will be under construction early next spring.”

The groundbreaking actually took place Oct 1, 1986.

NAYSAYERS

Not everyone was on board with construction of the museum, at least as a means of preserving the Mahoning Valley’s steelmaking heritage.

“We’re losing our identity as a steel town and I think a lot more could have been done than just design a $5 million ‘Tomb of the Unseen Steel Mills,” activist Richard Blackwell, a proponent of preserving the local mill structures, said in a September 1988 story.

An editorial about a year later, in our November 1989 edition, reflected on the shining of an unfortunate national spotlight on the museum as recorded in the article in the Oct. 30, 1989, edition of Newsweek, “The (Empty) Steel Museum.”

The editorial recounted how, in September 1988, Ohio Historical Society sought $1.2 million from the state for exhibit installation and furnishings. The governor’s office offered $360,000 in operating funds over the 1990-1991 biennium, a figure approved by the Ohio House of Representatives but slashed by the state Senate, in apparent retaliation over poor support by organized labor.

A compromise restored the funding that was recommended by the governor – a figure still inadequate for installing the exhibits and getting the museum on its feet.

Shortly before publication of the Newsweek article, the history society announced it would proceed with the first phase of installation using $400,000 from YSU and $25,000 remaining from construction funds for the building.

“It’s an unhappy and unfortunate thing, but we’ll continue to struggle, and we’ll get the job done,” Meshel, the museum’s longtime champion, assured.

By the following year, the job did get done – at least in part. On April 28, 1990, area leaders attended a preview reception for the two opening exhibits.

The first phase of the permanent installation was to be completed in the fall and completion of the second phase was slated for spring 1991, Meshel said. Funding was to come from the state capital budget.

The permanent collection opened about a year after what had been planned, on April 8, 1992.

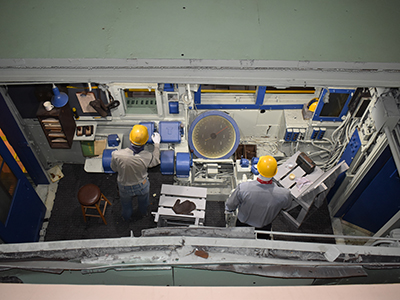

“Response so far has been tremendous,” David T. Wilson, the museum’s curator, said. From the first-floor overlook, museum visitors could view the inside of a blooming mill pulpit, which also could be viewed from the ground floor gallery.

Uncertainty over funding was a constant through the years. In the early 2000s, the museum appeared to be in danger of closing, as reflected in a July 2005 story that reported it had come “dangerously close… to suffering the same fate as the Mahoning Valley steel industry.” Instead, it had received a new lease on life, with the unveiling of a new exhibit earlier in the year.

Additionally, state funding for the Ohio Historical Society was expected to remain stable. The state had earmarked more money to promote the center and adopted a policy to let sites raise money independently to support their operations and educational programs.

“The Historical Society is trying to make the sites more entrepreneurial,” said Nancy Haraburda, site manager for the center.

She said the museum requires stronger local support and lamented that so many people in the community haven’t visited it and hold misconceptions about what it offers.

EXHIBITS AND PROGRAMS

In addition to containing the permanent collection, “By the Sweat of Their Brow: Forging the Steel Valley,” the museum hosted numerous programs over the decades.

They included, unsurprisingly, commemorations of Black Monday, the September 1977 day when workers were informed Youngstown Sheet & Tube’s Campbell Works would be shut down, which was followed by other mill closing announcements. In September 2012, the center hosted a new exhibit and labor symposium framed by Black Monday and the 75th anniversary of the Little Steel Strike, another seismic event in local labor history.

The exhibits and lectures were components of an overall plan to reenergize the museum, which was on the verge of closing four years earlier. YSU’s history department had assumed management, attracting traveling exhibits and lecture series, and foot traffic had increased. Exhibits also were attracting new donations.

“I think we’ve brought a new energy to it,” DiBlasio said.

Other programs included a February 2016 symposium, “East Youngstown Burning: Commemorating the Centennial of the 1916 Steel Strike,” an event precipitated by a fight over wages.

“You literally had mob rule in East Youngstown” – today known as Campbell – “that night,” said Bill Lawson, executive director of the Mahoning Valley Historical Society.

In October 2016, the center unveiled its newly renovated lobby and recognized the Bitonte family, which donated $50,000 to support the work.

The following year, in May 2017, a new exhibit highlighted household artifacts that people in the industrial Northeast manufactured, bought and sold from 1945 to 1965. The centerpiece of the exhibit, which was designed by YSU graduate students, was a complete Youngstown Kitchens set on loan from MVHS.

About the same time, a program the museum launched with YSU’s gerontology department, “Sparking Memories,” was aimed at helping individuals with Alzheimer’s disease.

“If they’re interested in one thing for 30 minutes, that’s what we discuss. That’s what is important to them,” said Amy Plant, a YSU adjunct professor who helped to create the program.

An exhibit funded by Vallourec Star that opened in 2018, “Seamless Transition,” explored the history of the local steel industry beginning with the discovery of coal in the 1800s at farmland owned by industrialist George Tod.

“The reason we’re here is because of the steel-making expertise and tradition in the Mahoning Valley,” Vallourec Star President Judson Wallace said at the exhibit’s grand opening Aug. 30.

In June 2019, AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka headlined a roundtable discussion with area workers at the museum. “Demanding Better: A Town Hall on Trade,” focused on the need to get a better deal in negotiations related to the North American Free Trade Agreement.

The following summer, in 2019, three new outdoor sculptures were installed at the center. The 400-pound sculptures – “Steel Worker,” “Soldier” and “Coal Miner” – joined sculptor George Segal’s “The Steelmakers” that had been relocated from downtown Youngstown in 2002.

In October 2019, the museum hosted an exhibit highlighting the history of modern labor in America that was part of the Smithsonian Institution’s traveling exhibition program.

In March 2020 – shortly before the museum temporarily closed because of the Covid-19 pandemic – it completed a project to digitize its collection of an employee newsletter published by Youngstown Sheet and Tube employees from 1919 to 1977.

Two new exhibits opened in 2021. One highlighted the role of the William B. Pollock Co. in the iron and steel industries, opened in September in the Bitonte Family Welcome Lobby and offered a virtual component. The other focused on the Youngstown General Duty Nurses Association.

In a June 2022 story about the museum’s 30th anniversary, an archives assistant recalled a man walking into the library a decade earlier requesting drawings of Sheet & Tube’s former Brier Hill Works. What she didn’t know at the time was that the visitor needed the information as the starting point for what would become Vallourec’s $1 billion expansion of its pipe and tube mill.

“Early on, they were clearing the section and wanted to know what was there before. They were interested in what they were finding in the ground,” Martha Bishop said.

One of the exhibits during that anniversary year showcased “The Art of Steel,” a selection of paintings and photographs selected from the museum’s permanent collection. Another was an update of the museum’s model railroad exhibit.

An exhibit the following year, “Hearing Our Voices: Discovering Black Youngstown,” was developed by DiBlasio’s museum curation class and opened in the center’s lobby.

“It’s not comprehensive,” DiBlasio said in February 2023. “It’s to give an introduction to the Black community and let people know about the rich history and idea of what’s out there.”

DiBlasio says the museum “helps us understand industrialization” not just in the United States but globally.

“We just have to focus on this region as a microcosm of the Industrial Revolution and what happened,” she says. “It helps us deal with questions of deindustrialization as well, and the things that follow in that wake.

“But on top of that, it’s such a complex story, because you’re not only looking at the technical part of ‘how do you make this stuff’ and why is it important,” she continues. “You’re also looking at how does the business run and who makes it work? Who are the people working there, from the top all the way down to the unskilled labor, and what are their lives like? That’s all a part of that story, and we don’t want to lose that story, because it’s part of who we all are.”

Pictured at top: Jonathan Cambouris is the administrator for the Youngstown Historical Center for Industry & Labor. Last year, the museum welcomed just over 16,000 visitors, according to a YSU spokeswoman.