Book Details David Tod’s Political Journey

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – For George Tod, it was assumed that his eldest son, David, would follow in his father’s footsteps, pursue the study of law, and perhaps plot a political course that mirrored his own during the first decades of the 19th century.

Instead, the younger Tod would break away from his father’s political philosophies, embark on a public career shaped initially by professional mentors and national heroes, and then sever those bonds later in life as the country hurled toward the bloodiest crisis in its history, culminating in his service as Ohio’s Civil War governor from 1862-1864.

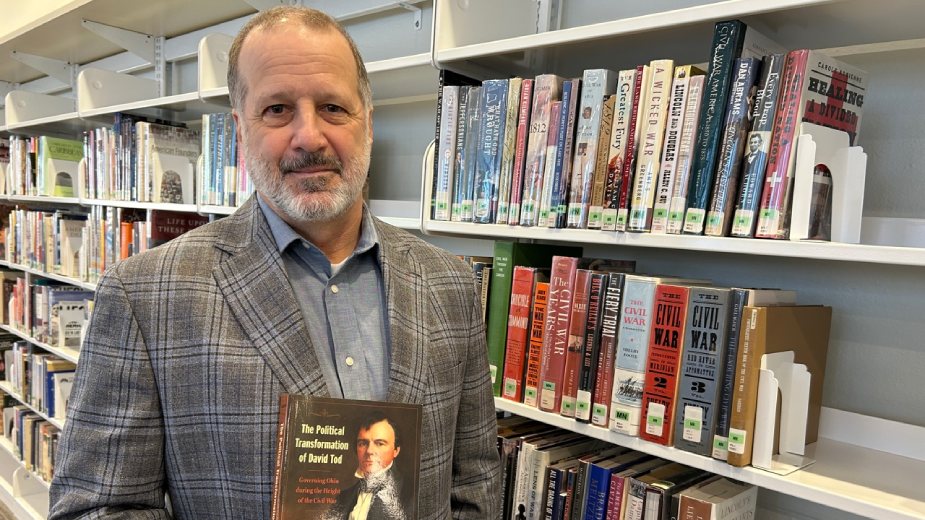

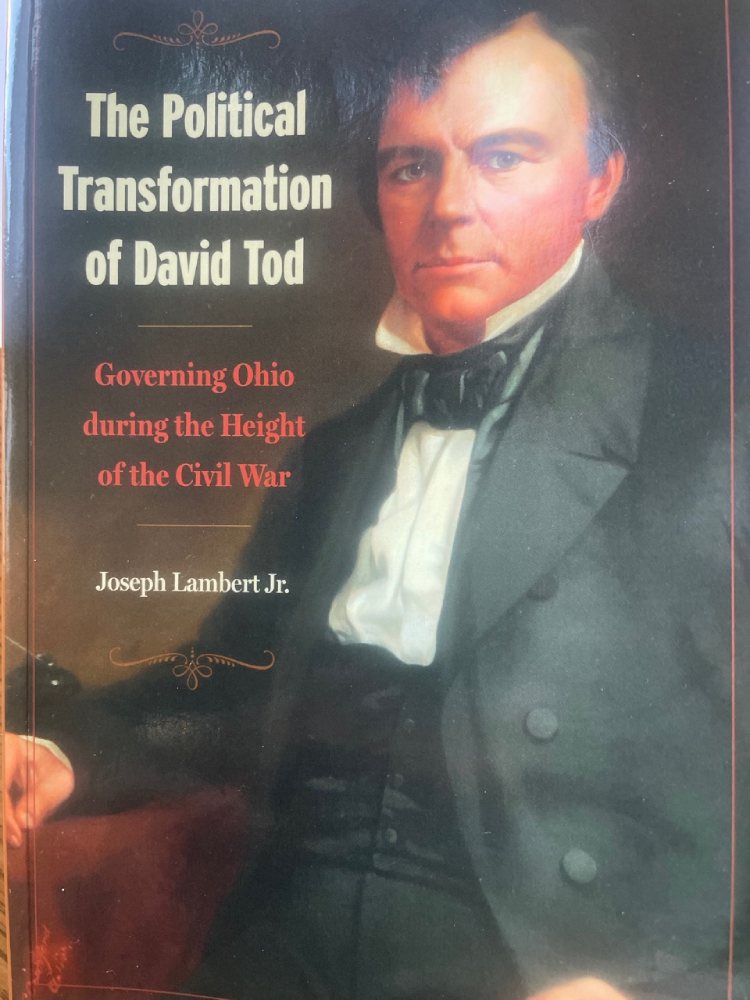

All of this is detailed in Joseph Lambert Jr.’s book, “The Political Transformation of David Tod: Governing Ohio During the Height of the Civil War,” published by Kent State University Press.

“It’s a story of one man’s political journey in Ohio,” Lambert said. “He, more than any other man, sacrificed his political identity and all the advantages that came with it. He put his party passions aside and put his love of country before anything else.”

Lambert, who earned his Master of Arts degree in history at Youngstown State University and is today a regional administrator at Windsor House Inc., Girard, said he became interested in writing the book – the first full-length biography of Tod – while pursuing his graduate studies during the early 1990s.

“When I found out that Abraham Lincoln had offered David Tod a position in his cabinet, I had to read about it,” he recalled. Lambert set out to find a book on the industrialist and political figure.

“Well, there were no books on David Tod,” Lambert said. “If you can’t find it, write your own.”

The book, published in November 2023, has attracted positive reviews from specialists in this field of historical study. Stephen D. Engle, of Florida Atlantic University, calls the account “a marvelous addition to the political history of the Civil War. By bringing Ohio’s David Tod out of obscurity, Lambert showcases Tod’s ability to rise to the challenge of putting the Union above party to restore the nation…”

FORMATIVE YEARS

By the time of Tod’s birth in 1805 in Youngstown, his father had already established himself as a political force in Ohio, having already served as prosecuting attorney for Trumbull County, a township clerk, and in 1804, elected to the Ohio State Senate. In 1806, he was appointed as an associate justice to the Ohio Supreme Court and volunteered to fight as an officer in the War of 1812.

Yet despite his political influence, George Tod, the patriarch of one of Youngstown’s most prominent families, struggled financially and was steep in debt. His 600-acre farm at Brier Hill was heavily mortgaged and the judge at least on one occasion faced foreclosure.

Still, he wanted the best for his son, Lambert noted, and called upon friends to help secure he and his brother’s enrollment in Burton Academy in Burton, Ohio, the equivalent of a prep school for college-bound students. Once David completed his studies, however, his father could not afford the tuition to further his education. Instead, a family friend, Rufus Spalding, agreed to take David under his wing and arranged for him to read law at a firm in Warren under Roswell Stone.

Both Spalding and Stone were both ardent supporters of Andrew Jackson, who in 1824 lost his presidential bid to John Quincy Adams — a remnant of the old Federalist Party that George Tod faithfully supported.

Breaking from his father, David Tod threw his weight fully behind Jackson and the newly minted Democratic Party. In 1828, Jackson would be elected to the presidency, the first of two terms in office. Tod had now discovered his political hero, and in return for Tod’s loyal support, Jackson appointed him postmaster.

“He also ran and was elected to City Council of Warren and served one term as mayor of Warren,” Lambert said. “Trumbull County wasn’t necessarily a Democratic stronghold, so I think it was more of his popular appeal to people.”

In 1838, Tod furthered his political career and was elected to the state Senate, where he served single two-year term. “He made a name for himself. He was a very impressive young man, and he was not shy about his abilities,” Lambert said. “He made good connections and was a forceful individual.”

BUSINESS AND FORTUNE CALLS

Lambert said Tod returned to Warren, then because of a prosperous law practice and a young, growing family.

Then, in April of 1841, George Tod died, leaving Brier Hill to David, who had helped stave off creditors from taking the estate several years earlier. What wasn’t known at the time was that buried underneath Brier Hill were vast seams of coal that crisscrossed under the property. Once David Tod took possession of the land, he began to experiment with coal outcrops found on the farm.

The coal found at Brier Hill was transformative, Lambert said, laying the foundation for Youngstown as an industrial powerhouse. “David Tod was perhaps the Mahoning Valley’s first industrialist,” he said. Soon, Tod began shipping coal along the recently completed Pennsylvania & Ohio Canal to Cleveland, where Great Lakes steamship fleets gobbled up the fuel.

“He was shipping tons and tons of coal by the canal, before the railroads,” Lambert said. Tod’s financial success in the coal business soon overcame his law practice, and he moved the family to Brier Hill permanently to look after his aging mother.

At the time of Tod’s death in 1868, Brier Hill – once 600 acres of unproductive farmland – held an estimated worth of $500,000, or roughly $11 million in today’s currency.

Tod’s financial security by the 1840s had allowed him the freedom to pursue other interests, and politics remained part of the industrialist’s pursuits. “It gives him the freedom and independence to keep his ear to the ground. He really had aspiration for higher things.”

ABOLITION AND THE GRADUAL BREAK

As a loyal Democrat, Tod was traditionally bound to the concept of state’s rights, a doctrine that southern states enshrined to protect the institution of slavery. Activists supporting abolition, however, had long maintained presence in Ohio and Trumbull County, and that antislavery sentiment was growing.

He had earlier staked a name for himself in the Ohio Senate, and party faithful had placed Tod’s name as a candidate for governor twice during the 1840s. Twice, the candidate lost.

Lambert attributes his losses to Tod’s inability to stake out a firm position in step with divided Democrats, avoiding issues such as slavery and attempting to appease voters of different party persuasions. “He was not very good at marketing himself as a politician,” Lambert says.

Throughout this period, Tod approached slavery as an issue that should be decided locally – a philosophy that would later be coined “popular sovereignty.” However, these views would change once Tod accepted a new post – ambassador to Brazil, offered to him by the new president James Knox Polk, a Democrat elected in 1844.

The transatlantic slave trade in Brazil was still very active, and it’s here that Tod witnesses firsthand the cruelties of the institution. Moreover, Lambert noted that Tod observed American traders illegally engaging in overseas trade of enslaved persons (the United States outlawed the transatlantic slave trade in 1808). Despite his protests to U.S. officials, little was done to stop it.

“It really makes an impact on him. I really think his five or six years in Brazil really made an impression on him,” Lambert said. “I think that’s one of the issues that turns him to maybe take a step when the time comes.”

That time would come during the political crisis of the 1850s, as the sectional division over slavery intensified. Tod’s rift with Democrats over slavery grew more pronounced under the presidency of Democrat James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, who openly sympathized with the southern cause.

WAR

The true break came after Lincoln’s election to the presidency in 1860, winning the electoral college including Ohio. Tod, who supported Lincoln’s rival, the northern Democrat Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, now found himself supporting the cause of the Union as southern states seceded and formed the Confederacy.

After South Carolina forces fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, generally instigating the Civil War, Tod never looked back. “That was it for David Tod. That was treason,” he said. “He was very much a pro-union man, regardless of his political identity.”

Tod threw his support behind Lincoln, and further backed an initiative to form a new Union Party that would bring together both Democrats and Republicans to meet the challenges ahead.

“He was seen as the guy who could perhaps unify divisions in the state of Ohio and was asked to run for governor,” Lambert said. Tod was elected to the office in 1861 and took office the following year, as Union prospects looked bleak.

As governor, Tod had to navigate a state that in many ways mirrored the country. Northern Ohioans heavily favored Lincoln, while sympathies to the Confederacy could be found in the southern portion of the state. Striking a balance would prove difficult for the Youngstown industrialist.

Among the most pressing issues were the draft and emancipation, Lambert noted. At the time, his political critics felt that Tod did not support emancipation forcefully enough.

Lambert has found otherwise. Citing a newspaper account written regarding a conference among northern governors in Altoona, Pa., the piece cites that Tod came out “quickly and enthusiastically for emancipation, but he doesn’t seem to get the credit for that,” he said.

Lincoln especially found Tod critical to Ohio’s support and liked the governor very much. Tod was present in the crowd during Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address (he is depicted in a now famous photo to the far right, just as Lincoln is stepping down from the dais) and remained loyal to the Union cause throughout the war.

In 1864, Lincoln, in return for Tod’s faithful support, offered him the cabinet post of Secretary of Treasury. Tod, who failed to secure the nomination for a second term as Ohio governor, declined the offer.

By that time, Tod was experiencing bouts of ill health, possibly a series of strokes, Lambert noted. He died on Nov. 13, 1868, at home in Brier Hill.

“At a time in which the nation was most severely tested, when it needed patriots more than partisan politicians, when it needed men of honor, it was fortunate to have such nationalists, such Unionists as David Tod,” Lambert concluded.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.