Valley Veterans Recall Grim Times in World War II

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — World War II ended nearly 72 years ago but memories of the conflict remain indelibly etched in the minds of four Mahoning Valley veterans.

One was taken prisoner of war by the Germans. Another nearly lost his life during the Battle of the Bulge. A third escaped being eaten by sharks after his vessel sank in the Pacific Ocean. And the fourth saw Japanese soldiers emerge from hiding after their government surrendered in September 1945.

Roy Gallatin of Warren saw action in the largest naval battle of the war.

The Germans took Daniel King of Lordstown prisoner in March 1945.

Howard “Howdy” Friend of Poland suffered a serious leg wound during the Battle of the Bulge.

And Booker Thomas Morris encountered some of the last Japanese holdouts during the Army occupation of the island of Saipan.

Their stories are among a dwindling number who can offer firsthand accounts of the most destructive war in history.

Sea School Saved Gallatin

Roy Gallatin joined the Marine Corps in August 1943 as the Allied offensive against Japan continued in the Pacific Theater. After completing boot camp, Private First Class Gallatin found himself sent to Sea School in San Diego. Among other things, marines were taught how to jump properly, if necessary, from ships at sea. “They had us jumping from 70 feet into the water,” he says. He didn’t think much of it at the time, but that training served him well.

Gallatin soon arrived in Pearl Harbor where the damage of Dec. 7, 1941, could still readily be seen. “The harbor was still full of ships that couldn’t move,” he remembers. While in Pearl Harbor, Gallatin joined a Marine detachment gunnery crew aboard the USS Princeton, an Independence-class aircraft carrier.

“The Princeton was attached to several different fleets while I was aboard,” Gallatin says. “We’d make speed turns at night from one fleet to another so that we could be in position for the next operation.”

The Princeton served with the Third, Fifth and Seventh fleets during his time aboard, he says. The carrier saw action across the Pacific including in Kwajalein, Eniwetok – now called Enewetak – New Guinea, Guam, Tinian, Saipan and Leyte Gulf in the Philippines.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf, the largest naval battle of the war, began Oct. 23, 1944. It was to be the last campaign for the USS Princeton. “We were bombed by a single dive bomber,” Gallatin says, “which struck the carrier between the elevators, crashing through the flight deck and hangar before exploding.” The bomb broke the fuel line for the boilers and started an enormous fire, causing the ship to lose power.

Other explosions rocked the vessel and the captain issued a general order to abandon ship. Having lost their life jackets to the fire, the surviving men jumped into the water with nothing to keep them afloat.

His training at Sea School quickly came back to Gallatin. “I remember I took a deep breath and I jumped,” he recalls. “It seemed like a long time until I hit the water and even longer after hitting the water till I stopped going down.”

Gallatin spent four hours waiting for a rescue craft. The USS Irwin ultimately arrived to rescue the stranded men. Part of the rescue included shooting at and ramming the sharks that attacked the bleeding marines and sailors. Ultimately, 108 men from the Princeton perished along with the ship.

Gallatin went on to finish his service in China. “I was returned to the States after about six months of duty in China, by way of Pearl Harbor and Chicago where I was honorably discharged on Dec. 13, 1945,” he says.

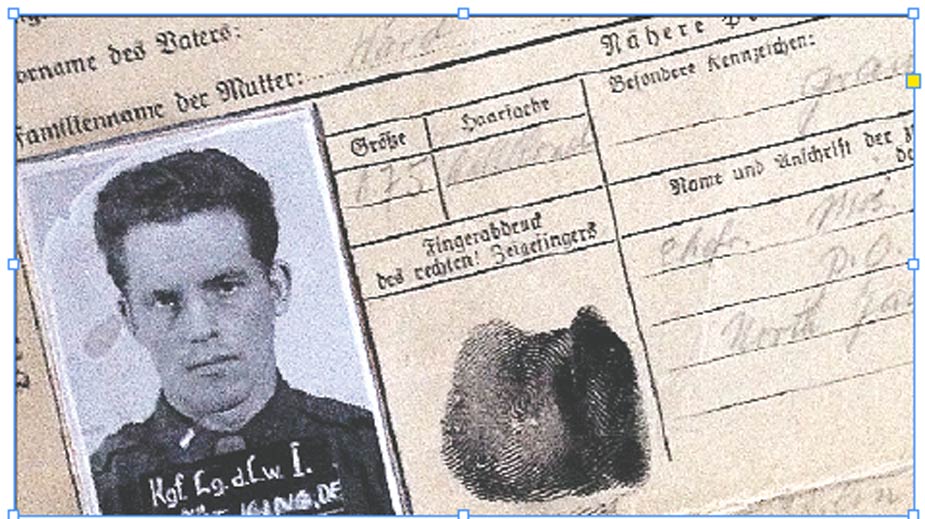

King Experienced Third Reich Firsthand

Daniel King is one of the last ex-prisoners of war from the conflict who lives in the area. “There used to be 40 of us, but now there are only four,” King says. As he grew up in North Jackson, he dreamed of enlisting in the Army Air Corps but lacked the two years of college necessary to be accepted into the flight-training program.

After passing a written test, he was admitted into the Aviation Cadet Training Program. He graduated from flight school in March 1944 and joined the 364th Fighter Group, 384th Fighter Squadron, Eighth Air Force Fighter Group based in Honington, England, in late November 1944.

King flew 30 missions in a P-51 fighter before he ran into serious trouble. While escorting bombers for an attack on Berlin, King’s wingman radioed him. “He said, ‘There’s something coming out of the back of your plane,’ ” King recalls.

It was an oil leak. He turned around, hoping to make it to the Allied-occupied section of the Netherlands, but was forced to bail out 50 miles south of Hamburg, Germany. By then the plane had caught fire and he barely managed to eject. “Next thing I know,” King says, “I’m up in the sky and the plane is gone.”

He was quickly taken captive and taken before a German official for interrogation. The gruff official, who hit his wooden leg whenever he wanted to make a point, told King that he had lost his limb during the Battle of Britain in 1940.

It was March 1945, and the end of the war didn’t seem far off, King says. “He told me, ‘I think we’re going to lose this war, but for a country that would fit into your state of Texas, we made quite an impression on the world.’ ”

During his time in Hamburg, King and his German guard were caught up in an air raid along with scores of other German civilians in an underground rail terminal. By this time, there were few men of any age who weren’t off fighting at the front. “Everyone in that air raid shelter was a woman,” King says. “I can’t remember seeing a single man.” When the civilians recognized King’s uniform, the crowd began yelling and spitting on him. By the time the guard removed him, King’s entire uniform was covered in spittle, he recalls.

King’s final destination was the POW camp Stalag Luft I, where he was held 45 days. Initially, King feared even taking a shower. “I had already heard about the [death] camps and I thought they were going to gas us.”

The camp was made up of several compounds and prisoners received a weekly ration of horsemeat with their meals. With the war nearly over, King and his fellow prisoners heard that Hitler had issued orders that Allied prisoners were to be shot. They weren’t, and Russian soldiers liberated the camp April 29, 1945.

While waiting to be transferred to the American lines, King and his fellow prisoners came across a nearby work camp filled with dead and dying prisoners. “There were dead bodies, and there were people alive that I didn’t think could talk,” he says. “They all eventually died and that left a lasting impression on me.”

In the Cold Outside Bastogne

Howdy Friend’s tour of duty in Europe nearly ended in death. He graduated from high school on D-Day, June 6, 1944, the boys in his graduating class expecting to soon receive a summons from their Selective Service Board. “I had already turned 18, so, boy, they drafted you right away,” he says. Eight days later, 14 members of Friend’s graduating class left for basic training.

Friend went to Camp Blanding, Fla., for 17 weeks of infantry training. “The Battle of the Bulge had started in Europe, and there was no question where we were going to go,” he says.

In December 1944, Hitler ordered an offensive through the Ardennes region in Belgium, France and Luxembourg in an effort to split the Allied armies. In a desperate effort to stop the Nazi advance, Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, ordered General George Patton’s Third Army, which Friend had joined, to relieve the besieged American forces at Bastogne in Belgium.

“We were in a holding pattern on the Saar River,” Friend recalls. They were pulled off the line and put on trucks bound for Luxembourg in late December. Friend, a machine gunner, was what the Army called a “replacement” – a new soldier sent in to fill the loss of a seasoned soldier killed or wounded in combat. Several feet of snow blanketed the countryside that December. “We slept in the Argonne Forest at night,” he says. “We just pushed the snow aside.”

It wasn’t long before Friend encountered trouble. “It lasted about two or three weeks,” he says. Near Bastogne, retreating Germans fired shells toward the Allies as they retreated. Shrapnel from a nearby exploding shell went through Friend’s left leg, severely wounding him. Soldiers pulled him into a nearby ditch but were forced to leave him behind.

“I don’t how long I laid in that ditch,” he says, but eventually a medic arrived to put a tourniquet on his leg and gave him morphine, although he was forced to leave Friend behind. The medic marked his location and a Jeep came some time later to take Friend to safety.

He was shipped back to the states in a full body cast. “I spent a year in bed,” Friend says. He endured several surgeries and eventually surgeons removed his kneecap.

But Friend was lucky, and he regained most of the movement in his leg. “By the end of the next summer, I could jog,” he says.

Morris’ Military Career Started in Pacific

Booker Thomas Morris of Boardman is one of few veterans to have served in the forces that occupied Japan after World War II and in the Korean and Vietnam wars.

“I signed my grandmother’s name to get into the service,” he says. It was 1945 and he was 17. He initially went to a Navy recruiting station in downtown Youngstown to speak to a recruiter. “He asked me if I could swim,” Morris says. “I said ‘No, man,’ so he took me down the corner to the Army recruiter and he said, ‘This is where you belong.’ ”

Morris, who is black, left a Youngstown that was segregated. “At McCrory’s [five and dime store] downtown, we couldn’t sit at the [lunch] counter,” he recalls. “We had to go around the side.”

The military, also segregated until Harry Truman issued an executive order mandating an end to the practice, proved similar. Segregation began in basic training and continued throughout all other facets of the military.

“At that time, the black soldiers were by themselves and the white soldiers were by themselves,” Morris says.

Morris arrived in Hawaii with the Army when the scars of Pearl Harbor were still visible.

“They were still cleaning up the port there after the Japanese had bombed it,” Morris recalls.

“After we did our chores, we went down to the beach and they showed us where the [Japanese] planes came in.”

Morris was then shipped to Saipan, which the Allies had taken a year earlier.

Once on the island, the soldiers heard rumors that some Japanese holdouts remained in the jungles. “We still had Japanese over there that hadn’t surrendered,” Morris says.

Gradually they saw signs that they weren’t alone. “We noticed our food was missing,” Morris says.

Eventually, the small number of holdouts became aware of the Japanese surrender.

“The next morning we looked out and saw foot tracks,” Morris recalls. “About 30 of them went over a cliff. They called it Suicide Cliff.”

Japanese military propaganda on the island claimed that American soldiers killed civilians and ate children, instilling enormous fear among the populace.

After the earlier Japanese surrender of the island, thousands of Japanese soldiers and civilians, including many women, jumped to their deaths from a place called Laderan Banadero.

After the war was over, Morris served in the Korean conflict before being sent to West Germany in 1954.

The West Germans – in the shadow of the Iron Curtain – came to see the Americans in a new light.

“The Germans liked us. They were nice,” Morris remembers. “Things had changed.”

Pictured at top: Daniel King still has his POW papers from his time imprisoned at Stalag Luft I.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.