Bridge Painters, Father and Son, Start at the Top

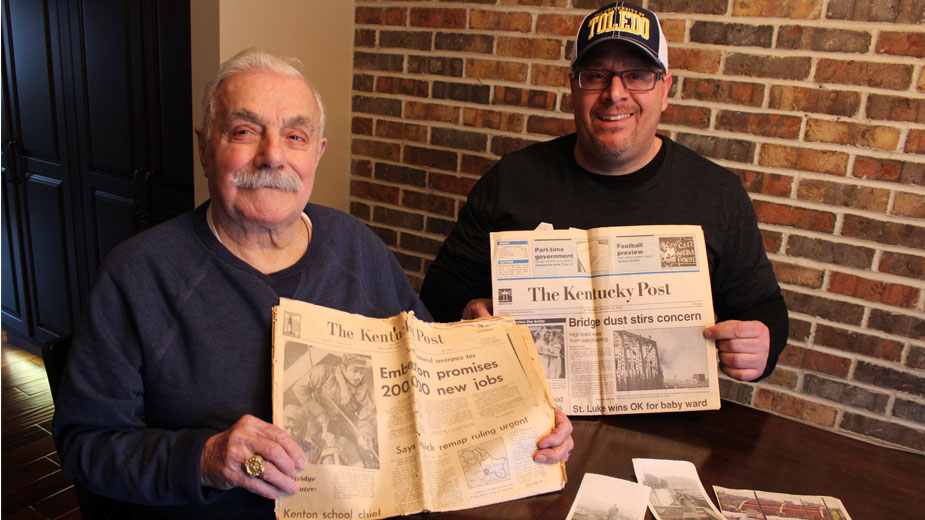

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — A photograph on the front page of the Kentucky Post dated June 14, 1971, shows a 41-year-old John Levendis performing paint preparation work on the Brent Spence Bridge, a double-decker structure that spans the Ohio River, connecting Cincinnati and Covington, Ky.

Nineteen years later, the Aug. 16, 1990, edition of the same newspaper published a front-page photo and story on painters refurbishing the same bridge. This time, however, Levendis wasn’t working on that project. His son George was.

“I used to take him with me when he was 14,” says John Levendis, today 89, glancing and laughing at his son from across their kitchen table in Campbell. “He used to always tell me he didn’t want to be a painter. But he never gave it up.”

The younger Levendis, now 50, is today president of Campbell City Council and the project manager for APBN Inc., a company that specializes in bridge painting services.

“I’ve worked in this industry my whole life,” George Levendis says. “As bridge painters, we travel all over the country – from Maine to California – and it’s hard, intensive work.”

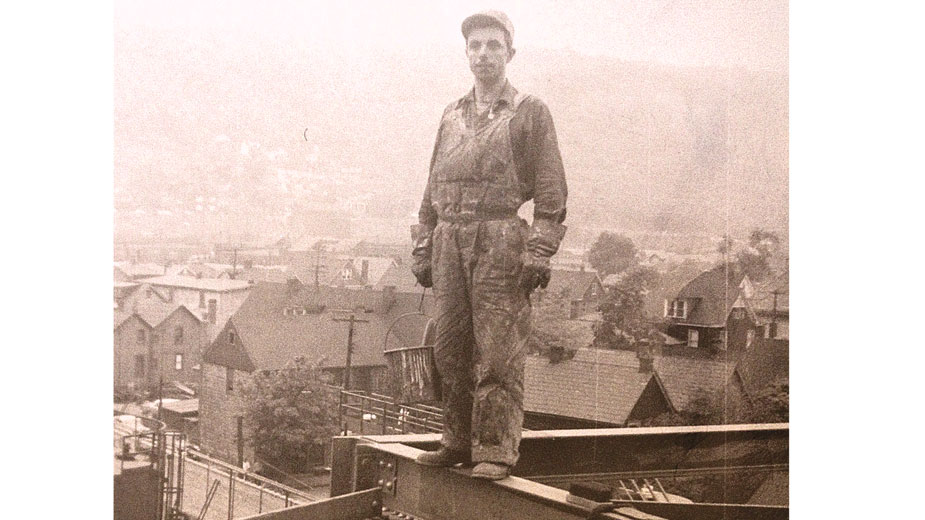

For John Levendis, his first day as an industrial painter started at the top – the very top.

“My boss took me to the job right away – it was the Fort Pitt Bridge in Pittsburgh,” he recalls. “He told me in order to break me in, I had to start high.” So, he and his supervisor scaled to the highest point of the bridge and began to work their way down.

“I learned how to climb. I learned how to rig. I learned everything,” he says.

It was Levendis’ introduction to a way of life that would take him across the country, performing these feats on bridges, industrial buildings and communication towers more than 1,000 feet above the ground.

In Levendis’ world, if it could be climbed, it could be painted.

A young John Levendis on the job. “If you were a good climber and a good painter, you always had a job.”

“I’ll be honest. Very few guys climbed as high as I did,” he says with his pronounced Greek accent. “Bridges, smokestacks, factories, towers, powerhouses – you name it.”

Levendis immigrated to the United States in 1953 and first settled in Ambridge, Pa., where an aunt and uncle lived.

In Greece, he was trained in the family business as a blacksmith on the island of Kalymnos, but decided to forsake that trade for a life in America when he came of age after World War II.

When he arrived in Ambridge, there were few industrial jobs available – GIs returning from the Korean War spoke for most of them.

“I had two choices: I could wash dishes or I could be a painter,” he says. “Painting paid more money, and they told me I would work six days a week, 10 hours a day. I was 21 and needed a job.”

Over the next 3 1/2 years, Levendis learned the basics through small, commercial paint jobs in the region. Then, a friend suggested he join the painters union and come to work with him for an industrial painting contractor that paid more money.

“At that time, it was $2 an hour,” he says. It was the same friend who climbed with him to the top of the Fort Pitt Bridge on Levendis’ first day. “He said, ‘Me and you are gonna work together,’ ” and mentored him during his first years as a bridge painter.

In 1961, Levendis married Maria, his wife of 57 years, and relocated to Campbell. Here, he landed a job at Masters Painting, a now-defunct company that was then on Wilson Avenue. “I worked there for 20 years,” he says, before taking a job with another painting firm based in Detroit and retiring as a supervisor there in 1998.

While at Masters, Levendis tackled some of the most challenging jobs in the region, including the broadcast towers – some as high as 1,100 feet. “I climbed like a monkey. I carried buckets up by hand. And there was a platform every 200 feet we would place our tools on,” he remembers.

It would take about 45 minutes to climb the towers, Levendis says. Painters would begin from the top and worked their way down.

Then there were the antennae atop the towers, which meant climbing another 75 feet with no safety harness. “A lot of guys wouldn’t do it, so I did,” he says. “That antenna would sway back and forth 20 feet in the wind.”

Underscoring all of this was the serious danger that faced these workers every day. Levendis says he’s witnessed co-workers fall to their deaths, while others were seriously hurt. Even he was injured when he fell about 20 feet during a job.

Safety regulations – or at least enforcement – during the 1950s and 1960s were practically non-existent across the industry, Levendis says. Workers would scale these structures without safety harnesses or masks to protect them from falls or lead-paint fumes. “At that time, if you wore a safety belt or a mask, they would send you home,” he says.

Climbing broadcast or high-voltage towers became very hazardous, Levendis says, because not only was there the threat of a fall, but also electrocution. “When I would go up, they would give me a light bulb,” he says. Should that bulb illuminate, it meant that electricity was escaping from somewhere on that tower or structure. “They’d tell me I’d need to get out of there fast,” he says.

Levendis spent most of his career on the road, painting bridges and large factories for companies such as General Motors and Ford. “I’ve done work almost all over – New York, Michigan, Tennessee, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Missouri,” he says. Little of his work was done in the Mahoning Valley.

Not so for his son, George.

“I’ve done a lot of local work,” he says. “Our company aggressively pursues it.”

Several years ago, the younger Levendis worked on repainting the iconic red “Mr. Peanut” bridge that spans the Mahoning River into downtown Youngstown. The company he works for, APBN, has refurbished or painted just about every major bridge in the region, including the state Route 711 connector.

A large part of George Levendis’ work today requires stripping off the very paint that workers such as his father applied decades earlier.

“We have to take off all of the lead paint from these bridges,” before any new painting can begin. “It’s critical that these bridges are painted, especially on this side of the country with heavy salt and corrosion.”

The trade has changed dramatically, George Levendis says.

“There’s a lot of training involved,” he says, and safety regulations demand all of those protections that the industry once addressed in such a cavalier fashion 50 years ago.

“Our union has a great apprentice program,” he adds.

All painting performed on bridges today, for example, must be done under a full enclosure to prevent potentially hazardous fumes from escaping into the air. Inattentive motorists traveling at high speeds on the highways are more likely to cause an accident for bridge painters than the work itself.

“It’s a totally different ball game now,” he says. And many of the local bridge painting companies are operated today by the second generation of families, he says. “You can make a great living at this, but you have to work.”

The elder Levendis never had to worry about that. “If you were a good climber and a good painter, you always had a job,” he says. “Always, I had a job.”

Pictured above: John Levendis and his son, George, hold copies of a Kentucky newspaper that reported on when they each painted the same bridge, in 1971 and 1990.

RELATED:

Fraternity of Bridge Painters Spans Culture and Craft

Daily Buzz: Campbell, the Greeks and Bridge Painting

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.