A Walkable Downtown is a Thriving Downtown

By Josh Medore

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – The completion of the Youngstown Foundation Amphitheatre has brought a new dynamic to downtown Youngstown, as throngs of visitors filled downtown for the inaugural series of events throughout the summer.

It’s likely to create a snowball effect, observes Justin Mondok, transportation planner at the Eastgate Regional Council of Governments. More traffic begets more traffic as people get comfortable with the area.

“As we see student housing and the hotel open up and the amphitheater and Covelli Centre hold more events, you’re seeing more businesses opening along Federal Street,” he says. “The activity is starting to grow and you’re seeing more people. And not just at certain times, but throughout the day.”

To get to their destinations, though, many have to cross the busiest streets in downtown. The Market Street bridge sees some 14,600 cars per day, according to the Ohio Department of Transportation. Front Street is the second-busiest thoroughfare in downtown Youngstown at 5,400 cars, while Commerce Street and West Federal Street handle 3,900 and 3,500 daily, respectively.

The increased activity downtown has brought with it new questions about how to best make the district walkable. One method was the installation of yellow crossing flags, intended to be held by walkers crossing streets, while other areas saw the installation of new signs alerting drivers to crosswalks.

“It’s not necessarily starting from scratch, but it’s asking how do we make improvements given the current state of infrastructure and resources,” says Sarah Lowry, director of Healthy Community Partnership Mahoning Valley.

Among the focus areas of the organization is active transportation. It’s an idea that focuses not just on walking specifically, but improving mobility as a whole, whether through pedestrian traffic, short-route transit or passenger vehicles.

“That also means traffic signals that allow enough time to cross the street safely. If you’re carrying items or have a stroller or a mobility device, it takes you longer,” Lowry says. “A lot of it is lighting. It has aesthetic benefits, but there’s also a safety element in that you can see where you’re going, which encourages people to choose walking from place to place.”

Earlier this year, Eastgate was awarded a $10.8 million grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation to develop the Smart2 Network to improve the Fifth Avenue corridor from St. Elizabeth Youngstown Hospital to downtown and continuing to Commerce Street and the Chill-Can plant on the East Side. Much attention has been paid to the project’s planned use of automated transit, but it also calls for upgrades that make the corridors more walkable, Mondok says. Among them are reducing the number of lanes on Fifth Avenue from the current six – three in each direction – to three total.

“Bringing those lanes in and reducing the number will reduce crossing time for pedestrians, making it safer and more convenient,” he says. “That’ll ultimately make it more attractive to development because you create a space people are more comfortable being in. Businesses really respond to that when they’re looking for site locations.”

In a study of spaces in Washington, D.C., in 2011, leases of sites easily accessible by walking were 27% higher than those in suburban areas and had a lower vacancy rate. And in a report by CEOs for Cities, walkability was found to increase property values by up to 9% and in the report’s 100-point walkability scale, a one-point increase was associated with an increase in home values of up to $3,000.

In the real estate market, observes Burgan Real Estate agent Lisa Resnick, walkability is one of the most in-demand features for developments. She points to the Firestone Farms area in Columbiana, which started as a residential development that expanded into office and commercial space.

“Those are the things people are looking toward. People want to be local when they’re shopping and in their lifestyles in general. It’s amazing that we have such a need for social media and online shopping, but because of that we have this desire to connect and meet,” she says. “Walkable cities are important and there’s a wave back to that type of experience that people are looking for when they want to move.”

Resnick also leads the Walking Wednesdays group, an offshoot of the Walk Youngstown campaign that meets weekly at sites across Youngstown. The trips don’t adhere to a specific distance, but instead are aimed at getting the idea of walking into participants’ heads.

“It’s getting people to think of something as not just a mile away, but as less than 20 minutes away,” she says. “When you put the timeframe on something, people are more apt to walk somewhere and then they’re more apt to find other stops to make.”

In that sense, walkability is also an economic development tool, Lowry and Mondok say. It’s easier for people to stop in at several shops if the district is walkable, rather than the one-and-done shopping that’s common with areas more conducive to vehicular traffic.

“The benefit, economically, to having a walkable community is that you’re getting people out of their cars and getting them to experience the built environment in a way that they can see the small business in a large building,” Lowry says. “You may not see that if you’re driving 25, 30 mph down the street.”

In downtown Youngstown, work is close to starting on turning Phelps Street between Commerce and Federal streets into a pedestrian plaza. It’s not terribly different from the idea behind shutting off Federal to traffic in the 1970s, an effort that ultimately failed. The difference this time, Mondok posits, is attitudes toward downtown.

“I wasn’t around when those decisions were made, but it seems that the installation of that particular piece of infrastructure didn’t really have the buy-in. Maybe they didn’t understand it and if you look at the timeframe it occurred, the city was facing its decline,” he observes. “It’s something that works well if you have an influx of people and development.”

Part of the development, Lowry adds, can be measures to improve health and safety. Surveys by the health departments of Mahoning and Trumbull counties find many adults report being overweight or obese, as well as having chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes. They also report having limited opportunities for physical activity. By making downtowns more walkable, it introduces more of those opportunities.

“Creating more walkable communities where people are able to build it into their daily routines encourages more physical activity, which can improve health outcomes,” she says.

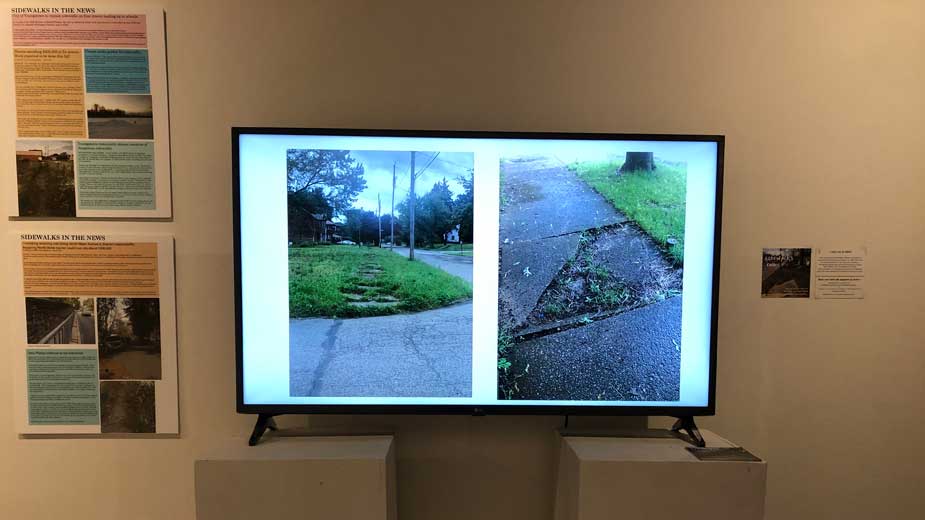

It also improves access to jobs, she says. Many reported not having their own vehicles and improving pedestrian infrastructure could make it easier to get to transit points such as bus stops. To showcase some of the challenges, the Healthy Community Partnership organized an art show, “Where Sidewalks End,” to highlight the state of sidewalks in the Mahoning Valley, with pieces from residents and professional photographers.

“The submissions we requested were looking at places where sidewalks didn’t exist where people were walking,” Lowry says. “We’re seeing sidewalks that end abruptly because of obstruction. We’re seeing sidewalks in such a state of disrepair that they’re not usable.”

In years past, addressing infrastructure was typically an either-or issue. It was built for either vehicles or pedestrians. It was designed to be residential or commercial. But new approaches, Mondok and Lowry say, are a healthy mix of everything.

“Everyone’s a pedestrian. At some point in your transportation, you’re walking from your house to your car or from your parking spot to your destination,” Mondok says. “It changes the framing of how we talk about how we travel. There are ways that we’ve done things for several decades and we can’t immediately cut that off.”

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.