BOARDMAN, Ohio – Ask Bill Davis a question about his service in World War II, and he’ll answer honestly.

At 94, the former resident of Youngstown’s east side and graduate of East High School now calls Briarfield’s Inn at Walker Mill home.

This Fourth of July, as many celebrate with fireworks and hamburgers on the grill, Davis and other wartime veterans will likely reflect on where they’ve been and what they’ve seen.

His daughter, Debby Metzger, visits once weekly and must keep to social distancing. Visits are held in the gazebo in front of the center after its executive director, Amanda Rivera, conducts a health questionnaire and takes everyone’s temperature.

Even though they are father and daughter, six feet separate Metzger and Davis, who sits in his wheelchair. For this interview, Metzger and Rivera relayed questions and answers for Davis, who is hard of hearing.

In 1943, Davis was drafted into the U.S. Army at 18 years old. He was part of the 63rd Infantry Division, 254th Regiment, Company G – nicknamed Blood and Fire.

“Growing up, my three sons called it the Blood and Guts Squadron,” Metzger recalls.

When Davis was deployed, his company landed in Italy and traveled across France, operating mostly at the border between France and Germany, Metzger says. After May 8, 1945 – what would be known as Victory in Europe Day, or V-E Day – Davis traveled to Berlin as part of the occupying army.

“After the war, they needed individuals who could speak German,” says Davis, who spoke fluent German and French.

In his role, Davis oversaw the import of logistics and supplies from the Army to Berlin, including food and medicine.

“If it went through Berlin, it went through me,” Davis says. “I had the final stamp.”

During his 5 ½-year tour in the Army, 2 ½ years were spent in Berlin, much to the dismay of his future wife, Delores, his daughter says.

“My mother was waiting to get married,” Metzger says.

When Davis came home from Germany, he arrived at the B&O station in downtown Youngstown; but there was nobody to meet him. Most of the other veterans had already returned.

Delores worked as a nurse at the former Southside Hospital and was living in the nurses home there. Unable to secure a ride, Davis walked from the B&O to Southside Hospital to visit his future bride.

Seeing her for the first time since his deployment was surreal, Davis says. He had known Delores while growing up and their families were close, he says.

At their 50th wedding anniversary celebration, Delores Davis told a story about growing up with Bill, Metzger says. In her younger days, Delores said she wouldn’t marry Davis “if he was the last man on Earth,” Metzger says with a laugh.

“I think she lived to eat those words a number of times as she repeated that story.”

When asked how he managed to change Delores’ mind, he calmly replied he’s kept that secret to this day.

Transitioning to civilian life wasn’t difficult, Davis says. After returning home, he worked for the government while attending Youngstown College, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry.

His first job was at Koppers Co. Inc., which produced tar from its operation near Crab Creek in Youngstown.

Later, when his two daughters were growing up, the family moved to Virginia where Davis worked as a chemist for an optical company.

Eventually, the family returned to Youngstown and Davis worked as an Environmental Protection Agency chemist for the city and Mahoning County.

It’s been 75 years since the war ended in September 1945. According to the National WWII Museum in New Orleans, 389,292 of the 16 million Americans who served in World War II were alive in 2019.

That number is much lower today.

During a reunion some years ago with his company in Columbus, Metzger recalls watching the veterans together. She witnessed a strong sense of camaraderie between them as they caught up and shared stories, she says. A stop to see the traveling Holocaust exhibit at Wright Patterson Air Force base, however, changed the atmosphere.

“I will tell you, men who hadn’t stopped talking the whole time they were there, you could hear a pin drop when they walked through this exhibit,” Metzger says. “It was very clear that many of them had horrible memories of finding people who lived and those who did not live through that experience.”

Davis has no kind words for World War II or what he saw during his time overseas, particularly while touring the Nazi concentration camps.

One of the more frightening moments came when he was shot in the shoulder during battle, for which he received the Purple Heart. After losing consciousness, he woke up in a French hospital staffed by nuns who were dressed in all white and wore cornettes – winged hats akin to the one worn by Sally Field in “The Flying Nun.”

The sight of the nuns shocked Davis; he thought he had died and gone to Heaven.

“That is a shock to wake up and see,” Davis says. “I looked around for St. Joseph.”

There are a few good memories from the war that Davis keeps with him, particularly “all the children I think I helped,” he says. Over the years, Davis kept in touch with some of the children through letters.

But when asked if he would do it all again, he answers with an emphatic “hell no,” and advises young men and women enlisting in the military to “stay the hell out.

“I killed too damn many people,” he says.

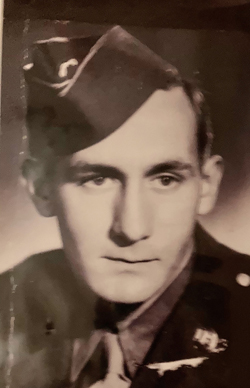

Pictured: Bill Davis sits next to a framed collection of photos and medals from World War II. He resides at the Inn at Walker Mill in Boardman.