Guest Commentary: Getting Real about Natural Gas and Jobs

By Sean O’Leary and John Russo

Ohio makes things.

Proportionately, Ohio has nearly 50% more manufacturing jobs than the country as a whole — one out of every eight jobs in the state. So, it’s not surprising that talk of a manufacturing renaissance based on expanding the petrochemical industry has captured the imaginations of many Ohioans.

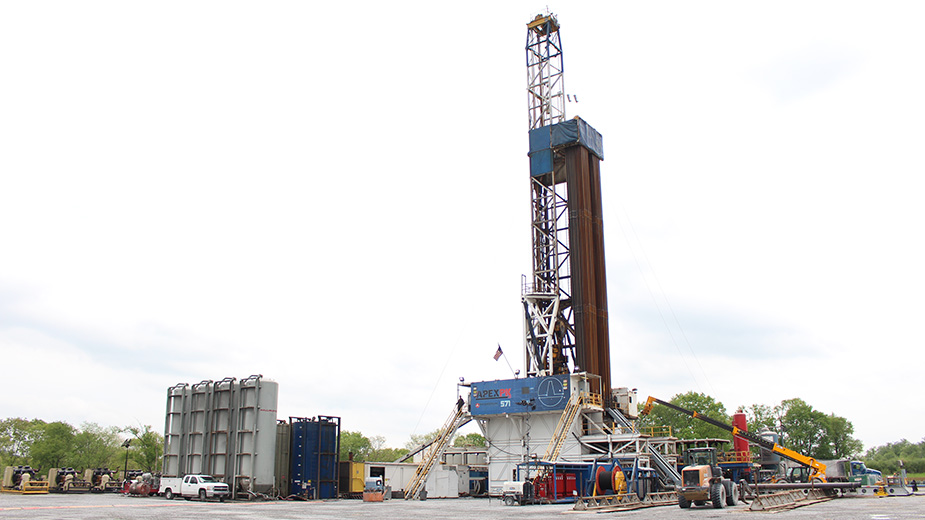

From the governor’s office on down, we’re told that the natural gas fracking boom can lead to a manufacturing resurgence, particularly in the areas of resins and plastics. And Lord knows it’s needed, since the fracking boom itself has conspicuously failed to deliver on promises of economic recovery and job growth.

Together the seven counties that produce over 90% of Ohio’s natural gas – Belmont, Carroll, Guernsey, Harrison, Jefferson, Monroe, and Noble – have seen jobs decline by 9% since the fracking boom began in 2007. Meanwhile, the rest of the state has seen an increase of 2%. So, it’s about time that the industry some called the region’s savior and an economic game-changer started delivering. But, if it does, it probably won’t be in manufacturing.

Why not? First, while industry backers claim that the fracking boom has saved manufacturers billions of dollars and made Ohio more competitive, the facts say otherwise. It’s true that since 2008 natural gas prices for industrial users in Ohio have dropped by more than 40%. But, Ohio’s average price was much higher than the nation’s to begin with and it hasn’t dropped as much. As a result, at least 29 other states currently offer manufacturers a lower price for natural gas, making Ohio less, not more competitive.

Second, industry economics are working against major petrochemical expansion in the region. That’s why in the more than four years since the Royal Dutch Shell ethane cracker plant in Beaver County, Pennsylvania was announced, not another major project has been greenlighted. In that time, three cracker projects have been cancelled or abandoned, the proposed Appalachian Storage Hub has failed to attract investors, and the only other major project still under consideration – a proposed cracker plant in Belmont County – has lost one principal investor and had its final investment decision postponed three times.

Third, even if the Belmont County plant gets built, jobs growth will be minimal. There would be a temporary spike in construction jobs, but permanent employment would only be between 400 and 600 in a region that has lost over 7,000 jobs. And what of the expected downstream jobs in plastics manufacturing? There won’t be many.

The American Chemistry Council and the US Department of Energy, both major boosters of Appalachian petrochemical expansion, acknowledge that 90% of Appalachian cracker output would be shipped out of the region for manufacturing elsewhere. And, of the 10% that stays in the region, much of it will replace feedstocks currently sourced from the Gulf Coast. To the degree that happens, local petrochemical output will merely support existing jobs, not create new ones.

In short, just as job growth from the fracking boom failed to materialize, the same is likely to be true of a petrochemical buildout, if it ever happens. And we risk repeating the cycle of industry executives and politicians promoting glorious visions of jobs and prosperity in order to win taxpayer dollars and greater freedom to pollute our water and air only to be stuck again with the subsequent reality of few jobs, reduced quality of life, and increased demands on public services.

If we care about new jobs and expanded manufacturing, we need to get real and look at where they’re happening – in the rapidly growing clean energy economy. Right here in Lordstown, we have a great example with the electric truck plant. Nationally, three-quarters of clean energy jobs are in construction and manufacturing. And most of those jobs come from local businesses — HVAC and lighting contractors, home remodelers, insulation companies, and other businesses that see their sales grow and, in turn, hire local workers.

That’s especially important in communities whose economies depend on coal and natural gas and which face job losses as those industries wither. We must fund a just transition to make sure those workers and their towns fully participate in the new opportunities and aren’t hung out to dry, which is what’s happening now as mines and power plants shut down. We must also help communities, which suffer disproportionately from the legacy of pollution those industries leave behind.

We can have widespread job growth in manufacturing and related industries, if we embrace the future and stop chasing smokestacks.

Sean O’Leary is the senior researcher at The Ohio River Valley Institute. John Russo is professor emeritus and former director of YSU’s Center for Working-Class Studies

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.