A Project that Paid Off: City to Send Final Covelli Loan Payment

YOUNGSTOWN – In a few days, the city will make its final debt payment on the $11.9 million loan it took out in 2005 to help fund construction of Covelli Centre.

It’s the latest milestone for the $42 million city-owned arena, which has hosted scores of concerts and events since it opened that year.

While Covelli has become a symbol of downtown’s rebirth and a magnet for visitors, its early days weren’t so smooth.

Although the city was able to pay off the construction debt in less than 20 years, it could have done so even faster.

For the first two years, the city lost money on the operation of the building – then known as Chevrolet Centre. The chorus of critics who said the arena was an unnecessary luxury grew louder, as the city paid only the interest on the loan for the first five years.

The first payment toward the principal didn’t come until 2011. But its fortunes changed as the arena found its place in the region’s entertainment landscape and became profitable.

For each of the past four years, the city paid $1.7 million toward the principal, according to city Finance Director Kyle Miasek. The final payment to Huntington Bank, the debt holder, will be made Jan. 2.

Much of the funding for Covelli Centre came from a $26.8 federal HUD grant secured by then-U.S. Rep. James Traficant.

In addition to the loan and the federal grant, construction was paid for using city money, earnings from operation of the building and naming rights fees. “No state dollars were used to build it,” Miasek noted.

Construction costs escalated as the city decided to build a state-of-the-industry arena.

“Back in 2005 when we were finishing construction, we had a difference of $11.9 million,” said Miasek, who was deputy finance director at that time. “[Then-Finance Director David Bozanich] put in a bunch of bells and whistles, because we didn’t just want a shell. We wanted something better.”

At that time, the city had received a guarantee from the state that it would get $4 million for the project out of the capital budget. It didn’t happen.

“Under that understanding, we figured $4 million [of the $11.9 million] wouldn’t be our responsibility,” Miasek said. “But those promises were not followed through by the people representing our area in Columbus, and as a result of [governing] party changes, Youngstown fell off the agenda in the governor’s office.”

Having to pay back the full $11.9 million ratcheted up the amount of interest due.

“If we had received those capital budget dollars, we could’ve paid it off sooner,” he said. “We could have saved a million dollars in interest.”

In total, the city paid a total of $6.6 million in interest on the $11.9 million loan, Miasek said.

“Interest rates were much higher then, and the facility wasn’t making money back then,” he explained. The rates varied by year, with the lowest being 5.3% in 2010.

As the arena became profitable, the city was able to make payments toward the principal. In 2011, the city implemented an admission tax, and that income was also used toward the principal, although Miasek said it “was not a huge component of the payments.”

The amount raised annually from the 5.5% admissions tax, which is levied upon all tickets sold for arena events, breaks down as follows:

- 2011: $216,000.

- 2012: $157,000.

- 2013: $197,000.

- 2014: $234,000.

- 2015: $211,000.

- 2016: $292,000.

- 2017: $166,000.

- 2018: $231,000.

- 2019: $284,000.

- 2020: $112,000.

- 2021: $118,000.

- 2022: $354,000.

- 2023: $323,000 (as of Dec. 15).

Operating revenue will continue to be used to fund maintenance and improvements at Covelli. The roof has developed a leak and will be repaired with operations revenue. “We will put it out for bid,” Miasek said. “We will spend up to $2 million on it.”

Earlier this year, the city repaired the building’s ice making plant for hockey.

History

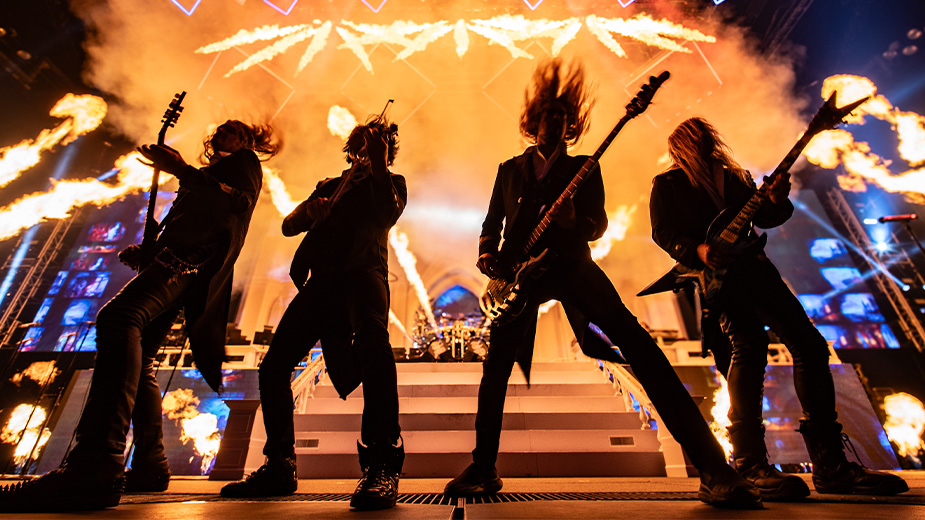

Covelli Centre’s first event was an Oct. 29, 2005, concert by rock band 3 Doors Down. A few days later, the late Tony Bennett performed there.

It was a successful start, but it wasn’t sustained and the arena would lose money for its first two years. With criticism returning, city officials took action.

The turnaround began in 2007, when the city parted ways with Global Entertainment – the management company it hired to operate the building – and hired Eric Ryan as interim manager until a permanent replacement could be found.

A factory worker at Wheatland Tube, Ryan was also the owner of The Cellar nightclub in Struthers. He had been booking national rock bands at The Cellar and at larger venues, including Beeghly Center at Youngstown State University and even a 2006 concert by Shinedown in the Covelli parking lot.

“I got a call by then-Mayor Jay Williams [in 2007], who asked if I would run the building so they could fire Global,” he said.

Upon getting the temporary deal at the downtown arena, he quit his mill job and formed JAC Management – an acronym for the first names of his children: Jordan, Ashley and Carson.

Within a few years, JAC would practically become synonymous with Covelli Centre.

Ryan got the contract on a permanent basis in 2008 and would go on to become a major reason for the venue’s success.

“I was aware of the naysayers and negativity but didn’t engage with it,” he said. “It was basically costing the city a million dollars a year.”

Booking shows that didn’t sell enough tickets was a major reason for its early stumbles, according to Ryan. “I don’t think they did a stellar job getting shows that people wanted to see,” he said.

When he was hired as interim director, Ryan figured he would have the job for only a year at the most. But he saw the flaws in the building’s operations and corrected them.

“I started making manager moves,” he said. “Making cuts, moving things and making financially sound decisions, booking shows that did well. But if anyone would have told me, or anyone at city hall, at that time that we’d have the building paid off in 2024, I’d have said you’re out of your mind.”

In his first full year at the helm (2009), Ryan and JAC made the building a moneymaker, posting a profit of $153,950. “We took it from losing $600,000 a year to making money,” he said. “We have never had a losing year since.”

Covelli’s best year was 2014, when it posted a surplus of $485,234.

From Day One, Ryan was tasked by the city “to right the ship and make Covelli self-supporting. That’s what we’ve done, and now it’s paid off.,” he said.

JAC Live, the event promotion arm of JAC Management, often working in collaboration with LiveNation, has brought many impressive shows and artists to Covelli. The list includes Elton John, Rod Stewart, Trans-Siberian Orchestra, Barry Manilow, Tim McGraw, Motley Crue, Alice Cooper, Carrie Underwood, Miranda Lambert, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Sugarland, Stevie Nicks and scores of others. The Ringling Bros. Circus, Cirque du Soleil and Disney On Ice have also made regular stops.

Ryan credits the foresight of city leaders for insisting on a facility that can accommodate modern tours.

“It’s a versatile facility,” he said, although he lamented the fact that it’s not suitable to lure conventions because of its limited floor space and lack of small meeting rooms for breakout conferences.

“The rigging systems are great; the acoustics are great; and there’s not a bad seat in the house,” Ryan said. “I sometimes wish we had more seats, but usually it’s absolutely perfect.”

Covelli’s seating capacity for a concert with the stage at one end is 6,300. That number includes the private luxury suites across the top of the seating area.

Learning the promotions business for a venue of that size in a tertiary market posed a sharp learning curve for Ryan that he quickly surmounted.

“Most other arenas have a promoter, but when we started, no one wanted to promote shows in Youngstown,” Ryan said. “So we had to run the facility and promote shows. We had to give artists guarantees [of income regardless of attendance], so we learned quick how to pick the right shows. When you’re writing big checks, you learn real quick. It was baptism by fire.”

Now that Covelli Centre and the Youngstown market have a successful track record, outside promoters – including industry giant LiveNation – regularly book shows here.

“We are on the map now,” Ryan said. “As long as outside promoters want to do shows here, that means we’re doing our job as managers.”

Today, JAC Live promotes about 10 shows per year between Covelli, Wean Park and The Youngstown Foundation Amphitheatre – it manages all three venues. The promoter pays the artist and assumes the risk of financial loss for a show.

Ryan says there is a limit to the number of shows per year that a market this size will support. Booking too many shows would cause ticket sales to suffer, and the arena would start losing money again.

He’s also keenly aware of the role Covelli Centre plays in luring people to downtown bars, restaurants and lodging. “We think about it,” he said. “It matters to us. We want our business to overflow into downtown before and after a show. We take pride in it.”

Miasek said Ryan and his company deserve kudos for Covelli’s successful run. “He built it from the ground up,” he said.

He also credited the city leaders at that time.

“How many cities our size have an A-plus facility?” Miasek asked. “The vision of our city government back then … you can’t put a dollar amount on it.”

Similarly, the Youngstown Foundation Amphitheatre, two blocks away, is another success story. Construction of the $8 million city-owned facility was funded by a $3 million grant from the Youngstown Foundation, $4 million in HUD grant money, sponsorship fees and some money from the city.

Though it’s open only during the warm months, The Amp has also been profitable.

In the first three quarters of 2023, Covelli, Wean Park and The Amp posted a profit of $368,269 for the city – well above the projected profit of $110,000.

Transforming Downtown

Twenty years ago, downtown Youngstown was abandoned, blighted and scary to visitors. It’s not hyperbole to say it was one of the most forlorn downtowns in the country.

Today it boasts breweries and bars, live music clubs, restaurants, a hotel and other entertainment options.

Covelli Centre’s history is intertwined with the stunning reversal of downtown.

But while its construction opened the floodgates for renewal, the seeds of revival had already been planted.

It started with a small group of people who had the foresight to create YAEDA – the Youngstown Arts and Entertainment District Association – and included a dash of good luck.

YAEDA’s goals were to bring nightlife, restaurants and bars, retail stores, housing and a means of late-night transportation to downtown.

To achieve them, the group first worked in City Hall and Columbus to change a state law so that it would allow for the creation of 15 new liquor licenses to be used solely in downtown and sold to bar owners for $2,844 apiece – a sum that was vastly under market value. At that time, liquor licenses went for around $20,000, provided one could find a seller, and the locations where a new licensee could open a bar were strictly regulated.

YAEDA’s start can be traced to a night in 2003, at the B&O Station bar, downtown. Businessmen David Simon and Dennis Roller and bar industry expert Bob Schott were discussing their plan.

Schott was actually tending bar that night.

Attorney Jeff Kurz, who had been a lawyer for only a few months at the time, walked in and quietly started reviewing some legal documents from his briefcase. He didn’t know the three men, but they took an interest in him.

“They asked me, ‘Are you a lawyer?’” Kurz recalled.

The three then told Kurz about their plans to create liquor licenses. Kurz, who was so new that he didn’t have clients, agreed to help – for free. The group needed a lawyer to write and file documents and found one that would work pro bono.

David Simon, whose family at the time owned Cedar’s Lounge, had the idea to adapt a state law that had been created to transform Columbus’ Short North neighborhood so that it would also cover downtown Youngstown.

Kurz drew up the legal documents, but getting the mayor and City Council to agree to it was no easy task – mainly because they did not understand the law’s intent. He met individually with then-Mayor George McKelvey and all council members, and eventually they supported the plan.

As their measure was being floated in Columbus, state Rep. Chris Redfern of Sandusky contacted Kurz. He wanted to further alter the proposed measure so that Sandusky would also be eligible.

Working together, they reduced the population requirement to about 20,000.

Another requirement was that each city be able to prove that it had at least $50 million of construction improvements underway in the entertainment zone. Thanks to the $42 million Covelli Centre project, Youngstown was barely able to reach that threshold.

The massive federal grant that came out of the blue and made construction possible is another unlikely element of the story.

Traficant’s securing of the $26.8 million federal grant was a rare coup for the divisive and confrontational congressman, who had more than his share of political enemies. It was also the final highlight of his career, as Traficant’s political downfall and eventual imprisonment began shortly after.

The synergy between YAEDA and Covelli became apparent at this time.

“We couldn’t have done what we did without the Covelli [construction spending], and Covelli needed us to succeed because they needed the liquor licenses,” Kurz said.

Kurz, whose law office is downtown, decided to put his money where his mouth is regarding the new law he helped create. He and business partner Brad Schwartz bought the first of the new liquor licenses and opened Imbibe martini lounge on West Federal Street in 2005. He and Schwartz would later buy another license and opened Ryes in 2013.

Covelli Centre purchased five of the licenses, with the rest going to new restaurants and bars downtown, including the Lemon Grove, Rosetta Stone, V2 and Roberto’s.

The transformation of downtown into a nightlife district had begun, and it dovetailed with the opening of Covelli Centre.

If it hadn’t happened, the new arena “would have been an island” in a sea of decay, Kurz said.

YAEDA, he said, provided a sturdy foundation to make the turnaround happen.

“When you are building in a hurricane zone, you have to have a strong foundation, and we did that,” he said, speaking metaphorically.

He acknowledged that the old, and often arrogant, attitude of Youngstown businessmen toward the city had to fade out and be replaced by a younger group that wanted change.

The turnaround of downtown took people with passion, education, knowledge, connections and a desire to take risks and do things a different way, he said.

The public’s perception of downtown as a dangerous place – although flawed – also had to change.

Despite popular opinion at the time, downtown never was a high-crime area.

Before he opened Imbibe, Kurz studied crime rates downtown and found they were equal to or better than that of Poland and Canfield, although most people didn’t think so.

Kurz praised the many politicians and business leaders who worked behind the scenes on YAEDA and Covelli Centre. The list includes, but is not limited to, Williams, Councilman Artis Gillam, T. Sharon Woodberry, Rep. Tim Ryan and Jan Strasfeld.

“YAEDA brought out the people who had the connections, the funding sources and the political goodwill,” he said. “They used their talents to make downtown better.”

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.