AM Radio Future Unclear. But Played Powerful Role in Baseball History

By MIKE FITZPATRICK, AP Baseball Writer

NEW YORK — Growing up in the Boston suburbs, Suzyn Waldman fell madly in love with two things: baseball and Broadway shows.

During the 1950s and ’60s, the long arm of AM radio brought both into her home.

“I can still hear Ned Martin of the Red Sox reciting poetry about the mountains in Anaheim,” said Waldman, the pioneer announcer and former star of musical stage who’s been calling New York Yankees games for decades. “I can still hear Curt Gowdy with that Wyoming twang.

“Not everyone can remember who their first television broadcasters were — but everyone knows who the radio team was. Everyone.”

Like many fans, especially older ones, Waldman originally got hooked by America’s pastime listening to ballgames on an AM signal. In fact, next month will mark the 100th anniversary of the first World Series broadcast to a national radio audience, when Graham McNamee and Ford Frick were among those who called the 1923 Fall Classic between the Giants and Yankees on NBC.

A century later, however, some consider AM stations a dying medium in the modern age of digital technology. Several major automakers are eliminating broadcast AM radio from newer models — prompting lawmakers on Capitol Hill to propose legislation that would prevent the practice for safety and other reasons.

A bill with bipartisan support, the “AM for Every Vehicle Act” is winding its way through Congress.

“Not all change is progress,” Waldman said.

To be sure, from satellite radio and streaming services to FM stations and cell phone apps, baseball fans nowadays have all sorts of options for tuning in their favorite team — even all 30 teams — whether their car features AM radio or not.

But those options aren’t necessarily free. And it’s not necessarily that simple.

Because for generations of fans, the warm memory of climbing into the family car on a hot summer night and finding the ballgame on that dashboard dial, leaning in to listen pitch by pitch with mom or dad over the persistent static of crackling AM airwaves, is the kind of age-of-innocence nostalgia that evokes “Field of Dreams.”

“I still like baseball on the radio,” John Thorn, official historian for MLB, said in an email. “I suspect that is not only because it is my favorite game, but also because it is a stop-action sport whose rhythms are well-suited to pauses, visualization by the listener, and reflection about the wonder of being ‘there’ at a distant game.”

Even if the future of AM radio is uncertain, there’s no denying its impact on the growth and popularity of baseball.

The marriage dates all the way back to Aug. 5, 1921, when Harold Arlin delivered the first play-by-play broadcast of a big league game between the Phillies and Pirates at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh on KDKA.

“Joined at the hip,” said longtime New York Mets announcer Howie Rose, who is 69. “What radio has meant to baseball and vice versa is probably the quintessential symbiotic relationship.”

It’s a romantic history, too, thick with unmistakable voices and signature calls forever immortalized as the familiar soundtracks to those grainy old highlight reels of Joe DiMaggio, Willie Mays and Ted Williams.

And beloved broadcasters, community icons still inexorably linked to their teams even generations later: Mel Allen (Yankees), Red Barber (Brooklyn Dodgers), Ernie Harwell (Detroit Tigers), Russ Hodges (New York Giants), Bob Prince (Pittsburgh Pirates), Chuck Thompson (Baltimore Orioles), just to name a few.

And charming tales, including a young Ronald Reagan, long before becoming the 40th president of the United States, announcing Chicago Cubs games in Iowa during the 1930s by recreating play-by-play at Wrigley Field that was initially transmitted via Morse code.

“Some clubs resisted the advent of radio, as they later would the introduction of television, believing it would deter attendance at the game,” the 76-year-old Thorn said. “But like the introduction of night baseball in 1935, radio had already brought major league games to the working class, and especially to women.”

Indeed, AM radio provided a gateway to the game for all sorts of folks at a time in America when ballpark stands were mostly filled with white men.

Before cable television took over, it was the long range of clear-channel AM stations that carried baseball all over the country and gave fans living far from big league cities the chance to follow a favorite team.

“Milo Hamilton and Ernie Johnson, Atlanta Braves, under the covers. My dad would come in, get on me, and then go, `What’s the score?’ The Braves, that’s the one thing we could pick up,” said 67-year-old Mets manager Buck Showalter, raised on the Florida panhandle. “Listening to Hank Aaron, Rico Carty. I can tell you the whole Braves lineup.”

KMOX in St. Louis, with its powerful signal reaching all over the central and southern United States, spawned countless Cardinals fans from Minnesota to Mississippi and beyond, as Hall of Fame broadcasters Harry Caray and Jack Buck described the scintillating exploits of Stan Musial, Lou Brock, Bob Gibson and more.

“You think about the teams that first started broadcasting on the radio, whether it was the Pirates or the Cardinals or the Reds, on these enormous clear-channel stations, it definitely grew the game,” said 65-year-old Mets announcer Gary Cohen.

“It definitely brought the game home for fans who were too far away to attend in person. At a time when most baseball was during the day and a lot of working people couldn’t attend, they could listen on the radio. So yeah, I mean, the connection between AM radio and baseball is not only one in terms of just entertaining the fans, but also creating fans.”

One of them was Rick Rizzs, the longtime Seattle Mariners broadcaster who spent his childhood on the South Side of Chicago.

“With that little magical transistor radio, that AM radio, you could not only get your teams, but maybe four or five other teams, wherever you were located,” said Rizzs, who turns 70 in November.

“So your baseball horizon was expanded, not just the Cubs and the White Sox, but to the Milwaukee Braves, at the time, or maybe when the weather was just right you could get the St. Louis Cardinals or the Detroit Tigers, or whoever was playing somewhere nearby. But because of AM radio, it expanded your chance to hear about all the stars that you had in your mind.”

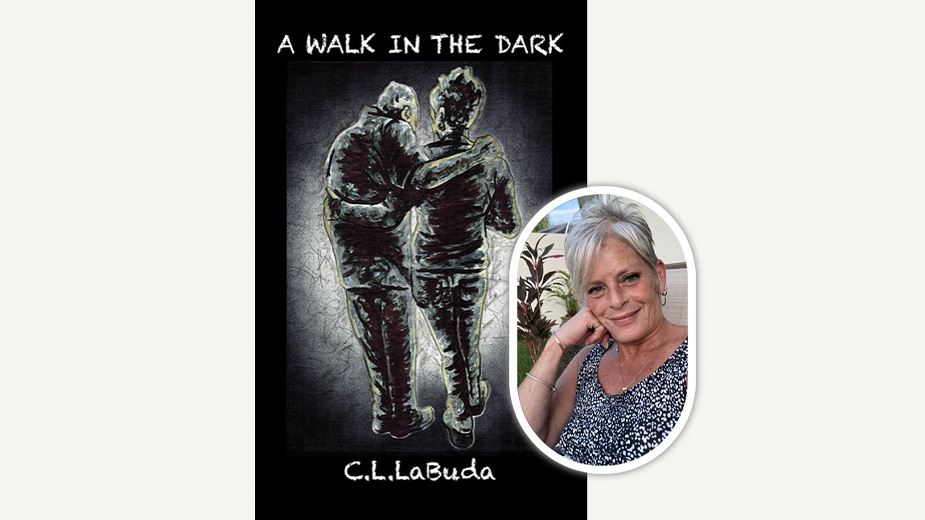

Pictured at top: Charlie Grimm, former Chicago Cubs manager, also worked as a radio broadcaster. He’s shown with Pat Flanagan, a broadcasting colleague., in this 1938 photo at Wrigley Field. (AP Photo/File)

Copyright 2024 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.