YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – The lead story on the front page of the Youngstown Business Journal’s December 1984 edition declared, “City Offers ‘Cheapest’ Money in Nation.”

The money in question was $683,000 in federal Community Development Block Grant funds that the city allocated to subsidize bank loans to businesses. With the community still feeling the reverberations of the steel mill closings that began in 1977 with Black Monday, local officials throughout the Mahoning Valley were looking at ways to lure businesses and encourage expansion, especially with bank interest rates at record highs.

As the story explained, businesses across the city were required to create one job for every $25,000 lent by the participating bank. Criteria for businesses downtown and on the Market Street corridor included removing blight. Once the bank agreed to make the loan, the city would make the first payment, an amount needed to reduce the total interest by eight percentage points, with grants ranging from $10,000 to $300,000, depending on the project.

“I don’t think there’s anything as unique as this program anywhere in the country,” then-mayor, Patrick J. Ungaro, boasted. “We’re thinking about advertising it in The Wall Street Journal, it’s that attractive to businesses.”

Qualifying businesses would pay more than a 5.5% interest rate to banks, according to the city economic director at the time, Charles Saulino. Banks participating were not allowed to lend money at a rate higher than two percentage points above the prime lending rate, which at the time was at 11.5%.

“This will make some borderline businesses bankable. They probably couldn’t handle the 13% to 14% interest rate, but now, they’ll have an easier time swinging the payments,” Saulino said.

According to the May 1985 edition of The Business Journal, the program had resulted in increased tax collections for the city. Ticor Tile began producing commercial floor covering inside a West Rayen Avenue building that had been vacated by Superior Beverage. The company would likely would have located elsewhere if not for the program, executives said.

But a month and a half later, the Mid-June 1985 edition of The Business Journal reported that the program had been placed on hold. Saulino cited two reasons: lack of funds and bad timing to seek a transfer of community development funds because of community complaints that the program had made no provisions to assist minority-owned businesses.

“We have approved every minority business proposal we have received from the participating banks,” Saulino said. “The problem is, the banks have not approved minority loans the way [some Black leaders] wanted to see them.”

Ungaro sought to address the concern with the promise of a separate assistance program for minority-owned businesses that would fall under the city’s affirmative action office.

Our next edition, July 1985, reported that City Council appropriated $125,000 to replenish the program, but that 16 businesses were in line with requests that added up to $400,000. Priorities for the funding were expected to include a proposed food mart in the former Rite Aid building downtown, additions to two automotive stores, expansion of a chemical company and a machine technology plant.

Since the program was initiated in 1984, the city had put up $1 million in federal funds leading to private commitments exceeding $5 million and community investments totaling $12 million.

One of the companies benefiting from the program was City Machine Technologies, which received a $10,000 subsidy to pay down interest on a $210,000 loan.

“At the time, that $10,000 was very critical to us,” CMT President Mike

Kovach recalls. It was days before he was closing the acquisition and every penny he possessed was in the deal.

“And we had five or six liens on our house,” Kovach adds. “In other words, there was nowhere else to scratch another 10 grand.”

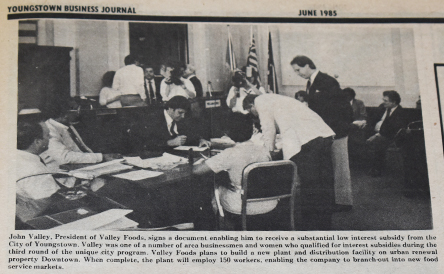

The September 1985 edition identified another handful of companies that had benefited from the program, including Valley Foods, which recently had broken ground on a new headquarters downtown to replace its Austintown facility.

In Valley’s case, because of the number of jobs created – 150 over a three-year period – and the downtown location, the city exceeded its guidelines, providing a $500,000 subsidy.

“It was necessary to make all the figures work,” Saulino said at the time. “We try to work with the businesses to give them the amount of assistance they need.”

In December 1987, the Youngstown/Warren Business Journal – rebranded to better reflect the publication’s regional focus – reported that Youngstown city officials were reviewing the expenditure of bank financing by five businesses, including a company that reportedly moved outside the city after receiving the funds, that had been awarded interest subsidy grants.

“When you look at the overall program, our record is very good,” Gary Kubic, city finance director, said at the time. Out of more than 100 grants, the city made “a few mistakes” but the city was going after the companies involved.

By our June 1988 edition, the city had formally terminated the program and officials were working on developing a replacement loan program. By August, the city was in discussions with Mahoning Valley Economic Development Corp. – today known as Valley Partners – to accept additional federal funds into the existing revolving loan fund it managed for the city as well as to manage loan funds earmarked for minority-owned businesses.

“In terms of efficiency, in terms of capacity, MVEDC is a logical entity to do this for the city,” Jeff Chagnot, then special assistant to the city’s Community Development Agency, said.

Pictured at top: “There was nowhere else to scratch another 10 grand,” remembers Mike Kovach, president of City Machine Technologies.