YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – There is something cool and even counterculture about silk screen prints.

It’s pop art with strong colors, but with a vibe of immediacy – and fun. It’s perpetually modern, even if its roots are in another era.

Gary Lichtenstein has been a pillar of the silk-screen art world for five decades. An exhibition of about 40 of his prints and paintings will open March 19 at the Butler Institute of American Art and run through June 11.

Lichtenstein, of Jersey City, New Jersey, will visit The Butler March 19 for a reception from 1-3 p.m. He also hopes to get a chance to work with students and artists while he’s in town.

In a phone interview, Lichtenstein talked about his lifelong connection to the art form and his upcoming show.

“A lot of my discussion about why I fell in love with silk screen predates digital technology,” he says. “We didn’t have computers. I came out of the period of rock ’n’ roll poster art, when I lived in San Francisco. Also, I knew it was part of a movement that made art affordable to people.”

Silk screening, like lithography and woodcuts, is a form of printmaking. It rose to popularity in the ’60s and ’70s as part of the pop art movement, when artists such as Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol and Charles Hinman created limited-edition sets of silk screen prints.

The physicality of creating silk-screen art also appeals to Lichtenstein. With computers, every step of creating art can be done on a screen nowadays, but he is not interested.

“I would never be happy unless I was making art by mixing paint with a stick in a can,” Lichtenstein says. “The artists I work with today know that this old-school technique has not gone away. They are so bored with the computer, they look at silk screening and say, ‘whoa, this is retro.’ I say, call it what you like, I’m good with retro. You got to get dirty.”

The process involves creating stencils and then adding paint to the medium in layers to create the finished piece. The steps can be repeated multiple times to create a series.

Silk-screen prints aren’t as “precious” as a painting, because “you can make more than one and you can play around with it,” he says, by altering the steps. “It’s the dialog with the process that gives life to art that could never be made any other way.”

Lichtenstein is not just an artist; he’s a mentor, and his studio is a destination for other artists who want to learn from him and work with him.

“I’m their best-kept secret,” he says.

The roster of artists he has collaborated with over the years include Alfred Leslie, Robert Indiana and the team of Eric Orr and Keith Haring.

He’s also made art with rocker Dave Navarro (Jane’s Addiction, Red Hot Chili Peppers), whose famed silk-screen piece “Black Dahlia” will be part of the Butler show.

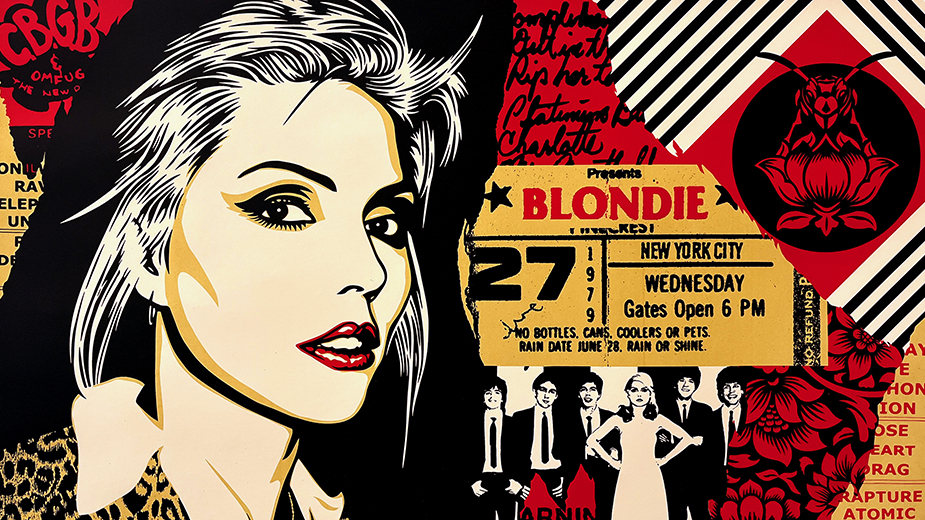

Another Lichtenstein colleague is the American muralist Shepard Fairey, who first gained attention for his prints of professional wrestler André the Giant and the word “Obey.” Fairey is best known for his iconic 2008 “Hope” poster depicting then-presidential candidate Barack Obama. His silkscreen piece “Blondie on Broadway,” depicting the avant-garde New York band Blondie, will be in the Butler exhibition.

Lichtenstein stresses that his upcoming show is not a retrospective. He made the majority of the pieces between 2000 and the present.

“There is no way I could encompass 45 years of work [in this show],” he says. “The through-line [of the show] is, I am first and foremost an artist, not just a silk screener, and all of the works are mine or work I did with other artists.”

The Butler exhibition will include some of his earliest silk-screen prints and also some of his paintings.

The idea for it started with Louis Zona, executive director and chief curator of The Butler and a long-time friend of Lichtenstein. Zona approached Lichtenstein with the idea last year and they worked together to select the pieces.

There is a story surrounding each piece, and Lichtenstein intends to share them when he visits. The best ones involve the collaborative work.

“Robert Indiana and Charles Hinman were friends of mine, and we all lived in the Lower East Side [of Manhattan] in the ’60s,” he says.

“I’m like what a recording studio is to a musician. They would come over with their own ideas and ultimately work with me on new projects or revitalizing an old project.”

Zona says that Lichtenstein’s place in the canon of contemporary art is significant.

“He has given so much to the American art world,” he wrote in a press release. “Working closely with enormously inventive avant-garde painters, sculptors and printmakers, [Lichtenstein] has advanced the visual arts in dramatic ways.

“His own creations represent continuous explorations and his genius for adding so much visual power to the creative work of colleagues fills a major gap.”

Zona sees Lichtenstein as an integral player in the unending evolution of art.

“When [museum founder] Joseph Butler envisioned his museum of American art in 1919, he surely was wanting to show American contemporary art at its best,” Zona says. “He would have welcomed Gary Lichtenstein to his roster of artists.”

Pictured at top: “Blondie on Broadway,” by Shepard Fairey.