YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – Area credit unions, regardless of size, face many of the challenges outlined in a Credit Union National Administration report issued earlier this year.

Nevertheless, several local credit unions are seeing growth in assets and membership.

717 Credit Union, based in Warren, boasts more than $1.3 billion in assets and more than $1 billion in outstanding loans, says Gary Soukenik, president and CEO. The credit union also is poised to hit 100,000 members.

“We’re kind of surprised at the growth we have this year,” Soukenik says. Assets increased 10%, primarily because of 11% growth in loans and deposits. Membership also has grown 11%, “which will help us hit that 100,000 mark.”

Mercer County Federal Credit Union, which has offices in Sharon and Hermitage, Pa., has grown from a $50 million credit union just five years ago to $105 million, says CEO Sandi Carangi. The credit union is adding more than 100 new accounts each month, thanks to an expansion of its community charter this year from just covering Mercer County to a total of seven counties in Ohio and Pennsylvania.

Loan volume also has rebounded to 2019 levels, as has new account volume, she reports. “I thought it would take us a bit longer,” Carangi says.

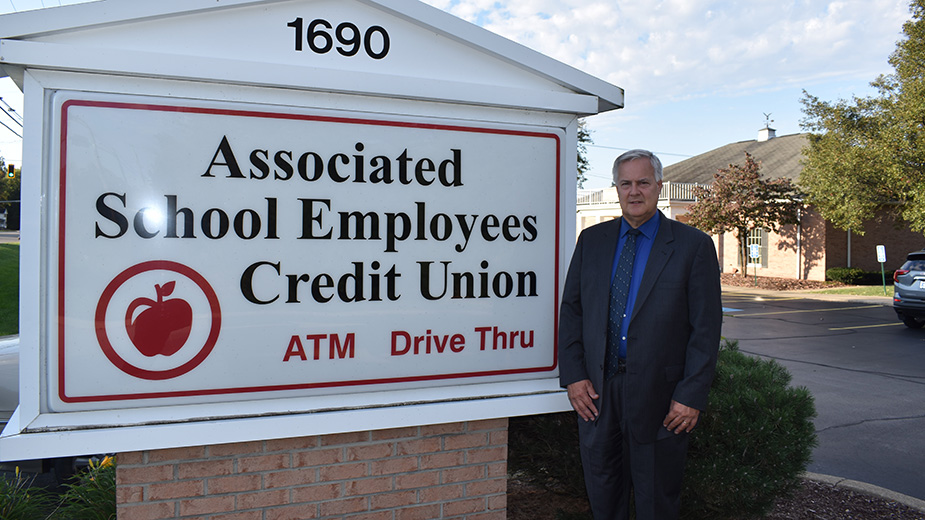

Associated School Employees Credit Union, based in Austintown, reports $170 million in assets, which is about the average size for an Ohio credit union, says Michael Kurish, president and CEO. Membership is around 14,500, up from about 13,000 just two years ago.

“That’s organic growth,” with the exception of the acquisition of a small credit union of less than 100 members, Kurish says.

The Diocese of Youngstown Federal Credit Union in Liberty Township, which this July marked its 50th anniversary, reports assets of $62.9 million, compared with the $8,576 it reported at its founding half a century ago.

Starting with a membership field of diocesan employees, membership now includes families of children attending diocesan or private elementary or secondary schools and parishioners of any diocesan church, says James Bellavia, chief financial officer.

Among the issues affecting the credit union industry as a whole is the net interest margin, the difference between the interest institutions make on loans and the cost of those funds, or “what we pay on deposits,” 717’s Soukenik says.

The difference between the two is at record low levels, he notes. “So we’ve got to watch other areas of expense, primarily operating expenses and loan losses, to make sure that we keep those levels very, very low.”

There had been a concern that loan losses might skyrocket during the pandemic but stimulus packages helped people keep current on their loans.

“The State of Small Credit Unions Today,” the white paper report by CUNA’s small credit union committee, defines six key challenges for this category, which CUNA defines as having $100 million in assets or less. They are technology, board leadership and engagement, member growth, generating income, health care costs and increasing overall costs.

Low interest rates have “greatly impacted” DOY’s investment income, Bellavia says. “Since our savings rates are greater than we can obtain from our investments, mainly federally insured CDs, we have to depend more on our loan portfolio. If we can’t lend out new deposits, then the excess has to be invested,” he explains.

Further, having a closed membership field affects the ability to attract new members, particularly younger members.

“Technology, especially in the cybersecurity area, has been a big expense and concern,” Bellavia says.

The challenge posed by keeping up with technology became even more apparent during the pandemic, when customers came to increasingly rely on to conduct business.

“We realized during the pandemic that people had to turn to technology and rely on technology. It was definitely very hard for small credit unions,” says Carangi from the Mercer County Federal Credit Union.

Logins to her credit union went from 8,000 per month to nearly 40,000.

“The technology we were using couldn’t handle that kind of volume,” Carangi says.

The greater reliance on digital transactions forced the Mercer credit union to implement changes planned to take place over two to three years to be put into place within months.

“It is a struggle for small credit unions to keep up with that. But fortunately we’ve been preparing for that for the past five years,” Carangi says. “We just had to do it quicker than what our original plan was.”

Also as a result of the pandemic, the credit union assisted members by waiving fees, lowering loan rates and allowing them to skip payments.

The pandemic affected the credit union itself, with overall income being “way down,” Carangi says. “We learned how to be very frugal during the pandemic. We didn’t have income coming in to cover our costs so we had to be very careful.”

Associated School Employees Credit Union already was devoting resources into its virtual products and online access and found “those technologies served us well” when the shutdowns hit, Kurish says.

Nearly every service ASECU offers was affected, he says. Electronic signatures rather than “wet signatures” – physical endorsements by pen – now can be used on documents ranging from loan applications and stop-payment orders to address changes.

Additionally, members can electronically transfer money from one financial institution to another, and to make payments, including using Automated Clearing house, or ACH, he says. People who had resisted using such tools in the past now find them to be convenient.

One of the benefits of these features, according to Kurish, is they provide an electronic journal for individuals. “At the end of the year they can go back and monitor how they’re spending their money,” he says.

“Members really started embracing them more so than any marketing campaign that we could have put together,” Kurish continues. “We were very fortunate that we were positioned to and postured well to deal with that. We’re looking to continue making upgrades in those areas and making improvements.”

Before the pandemic, 717 started installing personal teller machines, or PTMs, which the credit union has at all but one of its branch locations as well as a standalone unit in state Route 46 in Mineral Ridge.

“That was a way that our members could feel safe and transact routine transactions with us, and have somebody there via video to help them if they had any questions or issues,” Soukenik says.

Like all businesses, credit unions share the challenge of competing for workforce talent.

Soukenik says he’s heard reports that some 40% of workers are considering new jobs or might not go back to the ones they had.

Even though 717’s philosophy is to offer above-market in both pay and benefits to attract the best talent, “We have had situations where people have committed and they have accepted our job offer” but don’t show up on their first day or leave halfway through training.

“We never used to see that kind of thing before,” Soukenik says.

Adds Kurish, “There’s a lot of competition out there. So if you want to be attractive to that group you have to provide the benefits. That can be a costly venture for credit unions. That’s something that credit unions of all sizes are challenged with.”

The 717 and ASECU chiefs see a continued role for physical branches, although they might not look the same as in the past.

“We’ll see a lot more express branches, with small footprints,” such as the one 717 is developing in downtown Warren, Soukenik says.

“There’s always going to be a need for brick and mortar,” Kurish says.

Pictured: Gary Soukenik, president and CEO of 717 Credit Union, says new branches will have smaller footprints.