YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – In September of 1942, a newly minted B-17 bomber rolled onto the runway at Kellogg Field in Battle Creek, Mich. The Boeing aircraft, just off the assembly line, was assigned to the 303rd Bomber Group based in Molesworth, England, during the Second World War.

As was customary, the freshly painted olive-drab bomber came with a nickname, this one with the moniker “Jersey Bounce” written in prominent, cursive lettering on the left side of its nose.

The name would have been more than familiar to airmen during the period. In January 1942, Benny Goodman & His Orchestra’s arrangement of the foxtrot instrumental “Jersey Bounce” had shot up the music charts. The smooth melody and effortless saxophone work made it an instant hit and indispensable to the soundtrack of the swing era and the war years. Indeed, several other aircraft serving in the European and Pacific theaters adopted the name as affection for the song grew.

Those who purchased the record – a 78-rpm disc recorded on the Okeh label – would have also noticed the songwriting credits to the popular number. Along with saxophonists Bobby Plater and Eddie Johnson and lyricist Robert Wright (a pseudonym for Buddy Feyne) was bandleader Myron C. Bradshaw, better known to the music world as “Tiny.”

Bradshaw was born Sept. 9, 1907, in Youngstown, one month after his grandfather, Oscar Boggess, a former slave and decorated Civil War hero, died. A city directory from 1908 shows that Bradshaw’s parents, Cicero Bradshaw, a janitor, and his wife, Lilian Boggess, Oscar’s daughter, lived at 474 Edwards St. at the Boggess homestead on the city’s near South Side (See Part 1 of this series, “From Plantation to Civil War Hero,” in our July edition).

“I was eight years old when I first met him,” recalls Myra Bradshaw, Tiny’s granddaughter. “I’m the oldest grandchild.”

Myra, also born in Youngstown and who moved to Cincinnati during the 1960s, says she remembers her grandfather as a bigger-than-life figure who embraced all genres of music. “He was so very well-versed. He traveled everywhere.”

For some, Bradshaw never achieved the full recognition he deserved.

“He often had to sell the rights of his songs just to keep going,” says Marcia Melton, a distant cousin who now lives in Cleveland. “I had to go through England to get CDs of his work.”

Although Melton never met him – her mother and Bradshaw were cousins – she believes that he’s not been afforded full acknowledgement for his work. “I don’t think he ever got the credit he deserved,” she says.

Despite the success of “Jersey Bounce” – Ella Fitzgerald, Jimmy Dorsey and Glenn Miller all recorded versions of the song – Bradshaw is relatively unknown when compared to contemporaries such as Duke Ellington and Goodman. His work straddled an important transition in the history of American music and popular culture. His career intersected with just about every important jazz and blues musician of the 20th century.

Bradshaw took up the drums at an early age and later developed a love for the piano. After finishing high school in Youngstown, he enrolled at Wilberforce University in Ohio, a historically Black college, where he graduated with a degree in psychology. Nevertheless, he turned to music for a living, joining Horace Henderson’s Wilberforce Collegians during the late 1920s. He remained until the early 1930s. In 1932, Bradshaw left for New York City and joined Marion Hardy’s Alabamians as its drummer.

Two years later, Bradshaw formed his own band, a tight-knit orchestra installed as the headliner at the Harlem Opera House. In January 1935, a teenage jazz singer named Ella Fitzgerald entered and won a Harlem talent contest where the prize was fronting Bradshaw’s band as a singer for one week at the venue. During that stint, Fitzgerald met drummer and bandleader Chick Webb, who made her an offer to join his band. Her career was launched.

Others who went on to great success in the world of jazz passed through Bradshaw’s orchestra. Saxophone legend Sonny Stitt played in Bradshaw’s big band during the 1940s. There were also some missed opportunities with then-undeveloped superstar talent. As the band toured through East St. Louis, Ill., Stitt approached a 17-year-old trumpet player about signing up with Bradshaw’s outfit. But the trumpeter’s mother insisted he first finish high school. With that sound advice, Miles Davis declined the offer.

Bradshaw and his band found marginal success as recording artists during the 1930s. Much of the group’s appeal came from its live shows and Bradshaw’s rousing vocals and the band continued to tour across the country. During the war years, Bradshaw was commissioned as a major in the U.S. Army and conducted a 25-piece USO orchestra.

“He played with Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne, and knew all of the greats such as Duke Ellington,” recalls his granddaughter, Myra Bradshaw.

The big band sound ran its course in the years following the war. Talents such as saxophonist Charlie Parker and trumpet player Dizzy Gillespie – once sidemen in swing orchestras – broke out on their own and laid the groundwork for bebop and modern jazz.

Meanwhile, composers such as Bradshaw tinkered with parallel styles that incorporated blues and jazz with piano-driven, fast-paced tempos that were skillfully arranged.

What emerged was a distinct sound that became known as “jump blues,” eventually “rhythm and blues.” A few years later, the style branched off to what was called simply “rock ‘n roll.”

Although he had achieved some success as a bandleader and composer, Bradshaw’s real break came in 1949, when he signed with Syd Nathan’s King Records in Cincinnati. The recording label and studio, then known for its slate of country and bluegrass artists, had changed direction after the war to pursue the red-hot R&B market.

These included what were then called “race” records – songs written and recorded by Black musicians that by the end of the 1940s received limited airplay. Wynonie Harris’ version of “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” for example, was recorded and released by King in 1947 (Elvis Presley recorded his own cover in 1954) and it hit No. 1 on the R&B charts. King became the leading R&B label in the country.

Bradshaw, nearly 40 years old when he signed with King, achieved his greatest success with the label.

Myra Bradshaw says the composer often returned to Youngstown for family visits during this period. “He had a big Cadillac,” she recalls. “I remember it was the first one I saw with a phone in it.”

Bradshaw’s granddaughter says that his career with King Records was an indispensable contribution to early rock n’ roll and R&B. “He traveled the world,” she says. “He made a lot of money and he spent a lot of money.”

What impressed Myra the most about her grandfather was his attention to music composition and his versatile interests. “He wrote his own music and played all the instruments – the most important was the piano,” she recalls.

Her uncle, Gene Redd, also wrote and produced music at King during the later part of Bradshaw’s career. By the 1960s, the studio became home to major artists such as James Brown. “My mother did James Brown’s nails,” she says as she laughs. “I remember sitting in on one recording session.”

Myra was too young to witness Bradshaw’s sessions. His work at King proved to be a major influence on future generations who took his songs to heights unthinkable in the 1950s.

“He really was a pioneer of early rock n’ roll,” she says. In 1950, Tiny Bradshaw scored his biggest hit with “Well Oh Well,” a rollicking rhythm and blues piece that reached No. 2 on Billboard’s R&B chart.

“He received a gold record for that one,” his granddaughter says, the only such honor for the bandleader-turned-R&B hit maker. Regrettably, that gold record was destroyed in a fire, she relates. Several other popular records followed. “I’m Going to Have Myself a Ball” hit No. 5 in 1950. “Walkin’ the Chalk Line” reached No. 10 in 1951. “Soft” climbed to the third position in 1953 while “Heavy Juice” reached the No. 9 spot on the R&B charts that same year.

Yet it’s one song – not a chart success at the time – that cements Tiny Bradshaw’s legacy in popular music.

In October 1951, Bradshaw and his band entered the King studio to work out one of his new compositions. The arrangement reflects a transitional moment that fused jazz and jump blues with a subtle electric guitar. The lyrics to the tune were based on an earlier effort called “Cow-Cow Boogie,” a song written in 1942 for the Abbot & Costello film “Ride ‘Em, Cowboy.” Bradshaw rewrote it and added some lyrics:

I caught the train I met a real dame, she was a hipster and a gone dame

She was pretty from New York City and she trucked on down the ol’ fair lane

With a heave and a ho, and I just couldn’t let her go

The train kept a rollin’ all night long…

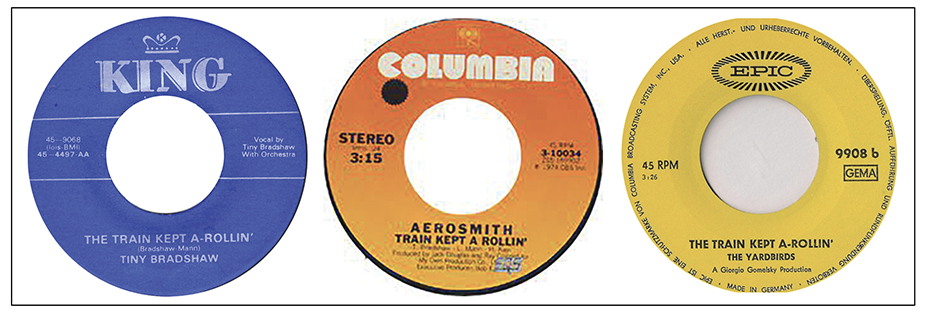

Released to critical acclaim in December 1951 but to little commercial success, “The Train Kept A-Rollin’” proved to be Bradshaw’s most enduring contribution to popular music. In 1956, Johnny Burdette’s Rock and Roll Trio re-recorded the song and transformed it into a rockabilly rendition that placed the guitar front and center instead of Bradshaw’s driving piano and saxophone arrangement.

Nearly 10 years later, it was this version that caught the attention of a young guitar player from Wallington, England, named Jeff Beck. According to Larry Birnbaum’s “Before Elvis: The Prehistory of Rock n’ Roll,” Beck claims to have introduced the song to his new band mates, The Yardbirds, among the biggest British blues and rock acts. According to Birnbaum, Beck, who joined the band in 1965 to replace Eric Clapton, said: “They just heard me play the riff. And they loved it and made up their version of it.”

The following year, The Yardbirds appeared in a brief club scene in Michelangelo Antonini’s film, “Blowup.” The band launches into a rousing metal-influenced interpretation of “Train” that features Beck and the Yardbirds’ newest addition, guitarist Jimmy Page.

When the Yardbirds disbanded in 1968, Page took the song to a new group he recently formed, initially called The New Yardbirds but later renamed Led Zeppelin. The first song the band rehearsed, according to Page biographer Mick Wall, was “The Train Kept A-Rollin.’ ” Led Zeppelin never released its versions commercially during its recording career. The song, however, remained a staple of the band’s early live performances.

By the early 1970s, the song had become part of the permanent repertoire for another upcoming rock band, Aerosmith. Joe Perry, the band’s guitar player, recalls meeting lead singer Steven Tyler and working out some early run-throughs of songs and hit on the Yardbirds’ version.

“For us, it was just that one song,” Perry told an interviewer in 2013. “The song we had in common was this song called ‘Train Kept A-Rollin.’ I don’t think we realized it, at that point, how important it was to us.”

In 1974, Aerosmith’s adaptation of Bradshaw’s song appeared on the band’s second album and quickly became a favorite of FM rock stations.

Bradshaw didn’t live to see what he’d started. After surviving three strokes, the Youngstown-born bandleader died in Cincinnati on Nov. 26, 1958, at the age of 51, where he is buried.

The song has since taken on a life of its own. Burnette’s version is included in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s exhibit “500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll.”

During the 2009 Rock Hall induction ceremony, the stage was crowded with some of the best guitar players in the music world. For their closing number, Ronnie Wood of the Rolling Stones and the heavy metal band Metallica joined Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page and Joe Perry for a rousing finale.

The song they selected to perform was “The Train Kept A-Rollin,’ ” a nod to Bradshaw and a Boggess family legacy that began on a Virginia slave plantation in 1832, came of age in Youngstown, and then presented for all the world to hear.

Flashback is sponsored by Hickey Metal Fabrication based in Salem.

Pictured at top: The crew of the B-17 bomber “Jersey Bounce” gathers around the aircraft named for a hit song co-written by Youngstown native Tiny Bradshaw in 1942.