First of a two-part series

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – This story begins on a Virginia plantation in 1832 and ends in 2009 with a fierce guitar performance by Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Ronnie Wood and the heavy metal band Metallica.

And the entire tale courses through a small homestead in Youngstown.

Just off the 400 block of Edwards Street on the city’s near South Side sits a vacant lot where an Ohio History marker stands. Its base is fortified with brick pavers and maintenance workers are busy performing some routine landscaping on a sunny morning.

Few in the Mahoning Valley know of the marker, let alone the person to whom it is dedicated. But the legacy of the family who lived here reverberates today.

“Oscar Boggess was an important member of this community,” says Steffon Jones, a local historian who has spent more than a decade conducting research on the Boggess family. Boggess was among the first Black Americans to settle in Youngstown in the years following the Civil War, securing a 2 3/4-acre plot along Edwards Street.

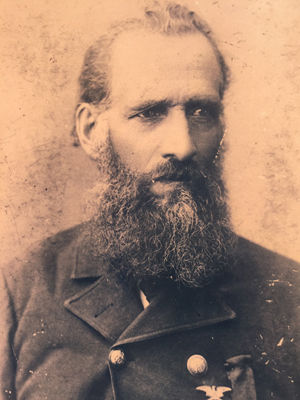

Boggess, a decorated war veteran and stonemason, was responsible for laying the foundations of the building boom in early Youngstown during the postwar years. He used block quarried from an outcrop of sandstone at the rear of his property.

In 2006, a committee composed of Jones, Mahoning County Historical Society Executive Director Bill Lawson and the late Edna Pincham, honored Boggess with the marker, situated close to the homestead that is now long gone. It was the first history placard in the city to honor a Black resident, Jones says.

Amazingly, the marker also represents a sweeping family history that touches upon slavery in the antebellum South, service during the U.S. Civil War, the early migrations of Blacks to the North during the latter half of the 19th century and the birth of rock ’n’ roll.

Oscar Boggess was born Sept. 15, 1832, to Richard Boggess and his slave Phoebe in Harrison County in what was then Virginia but is today West Virginia. According to court records, Phoebe was the mother of six children living with Richard. By all accounts, it appears Richard expressed the same love and affection toward Phoebe and the children as any husband and father.

“They were treated like they were family,” Jones says. “She was his wife and her children were his children.”

Still, Virginia law forbade marriages between Blacks and Whites, slaves and slave owners. Thus, the legal status of Phoebe and her children didn’t change during Richard’s lifetime. They were slaves.

Then, in 1843, Richard Boggess fell ill. As he lay dying, Boggess presented one final gesture intended to ensure his family’s future and their security. On his deathbed, Richard Boggess dictated his last will and testament, declaring that Phoebe and the children be emancipated and his 300 acres sold. The will stated that the proceeds from the sale would go to the purchase of property in southwestern Pennsylvania for Phoebe and the children. There they would live as free citizens forever. Richard Boggess died just hours after dictating his will to witnesses, who transcribed the document.

Some of the older children – particularly 16-year-old Abel – were skeptical. Fearing the will would not survive a potential legal challenge from Richard’s siblings, brothers Rolla and Abel fled north, Abel to Pennsylvania and Rolla to Youngstown. Considered a fugitive slave under federal law, Abel evaded capture and moved north through New Castle, Pa., before turning west into Ohio, where he sought refuge in Trumbull County. He then settled near West Andover on the farm of Anson Garlick, who took him in.

Abel worked on the Garlick farm for three years while attending school. In honor of his benefactor, Abel changed his name to Charles Garlick, ventured into Canada, but eventually lived the rest of his life in Ashtabula County.

Abel was correct about Richard’s siblings and their intentions. “When he died, his brothers contested the will – they wanted the land because of its rich mineral deposits,” Jones says.

In a fascinating turn of events, the case found its way to the Supreme Court of Virginia in March of 1844. The case, Phoebe & others v. Boggess & another, considered whether slaves could be freed under a nuncupative will – that is, a will that is orally dictated by a person who is too sick to make a written declaration. The court ruled that the will was valid in respect to the emancipation of slaves but not Richard’s property, which the brothers inherited.

Still, Phoebe and her family, including 11-year-old Oscar, were free.

Phoebe eventually settled in southwestern Pennsylvania, near Smithfield in Fayette County, where she died in 1894 at the age of 103.

Oscar, after several years of working on a farm in Monongalia County – today in West Virginia – moved north into Greene County, Pa., at age 20. He moved to just west of Fayette, where he was first employed as a farmhand and then honed his craft as a stonemason. Boggess was there in April 1861 as news spread of the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter – the first artillery salvo of the Civil War.

According to an account of his military service published in the Youngstown Telegram on June 25, 1902, Boggess attempted to enlist at a nearby recruiting station “where he tendered his services, but at the time was told his services where not needed because this was a ‘white man’s’ war.”

It wasn’t until passage of the Militia Act of 1862 that Black troops were allowed to enlist. President Abraham Lincoln signed the legislation into law on July 17, 1862, and shortly afterward, African-American men joined volunteer regiments in New York and Illinois. After the Emancipation Proclamation took effect on Jan. 1, 1863, the War Department officially authorized Black recruitments and the establishment of United States Colored Troop regiments.

A muster list published in 1866 shows that Oscar Boggess joined the U.S. Colored Troops’ 43rd Regiment, E Company, on March 21, 1864.

According to records, he was promoted to sergeant on April 5 of that year and first sergeant on Feb. 1, 1865. He was mustered out with his company on Oct. 20, 1865.

Boggess and the 43rd were among the Union soldiers who participated in the siege of Petersburg, Va., the Southern gateway to the Confederate capital of Richmond. The nearly 10-month campaign from June 1864 to early April 1865 saw some of the war’s bloodiest fighting and was also known for the high density of Black regiments who took part.

In particular, Boggess was present at one of the more horrific episodes of the Petersburg campaign, the Battle of the Crater. Gripped in a stalemate with Confederate forces just south of the city, Union commander Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants proposed an innovative plan to break the deadlock. His idea was to tunnel a long shaft under Confederate fortifications, pack it with explosives and then blow a massive hole in the enemy’s lines so Union forces could breach their positions and fight toward Richmond.

It didn’t go well.

Early in the morning of July 30, 1864, the explosives in the mine detonated, causing heavy damage to Confederate defenses as well as casualties. It left a massive, 30-foot deep crater.

Union troops, however, failed to seize the initiative. The delay allowed the Confederate defenders to regroup. As Union forces charged into the crater – many believing it would serve as protection against a Confederate counterattack – they were slaughtered.

Boggess and the 43rd, however, maneuvered around the crater and succeeded in piercing Confederate defenses. According to the Telegram account, Boggess was among the Union troops who captured a rebel battle flag and five enemy soldiers, even though his regiment retreated and the battle ended in a Confederate victory.

Significantly, many credit Boggess for preventing members of the 43rd from murdering captured Confederates in retaliation for the Fort Pillow Massacre in Tennessee nearly four months earlier. In that incident, more than 300 Union troops, most of them Black, were gunned down by Confederate forces after they surrendered.

“A lot of them wanted revenge for Fort Pillow,” Jones says. “But Oscar rallied his men and instead they were taken as prisoners of war.”

Boggess was awarded the Butler Medal of Honor for his bravery. “He was very proud of his service to his country,” says Bill Lawson, executive director of the Mahoning Valley Historical Society. Several other members of the Boggess family, including his brother, Richard and his nephew Elisha, also served in colored troop regiments during the war.

After the war, Boggess returned to Pennsylvania. In 1866, he bought the land on Edwards Street in Youngstown and began his career as a stonemason.

“He was one of a number of skilled tradesmen who made their way to the Mahoning Valley during the 1860s and 1870s,” Lawson says. “Really, it was the city’s first building boom. The wealth and affluence was growing and its political influence was growing.”

Boggess worked closely with the talented African-American architect and builder P. Ross Berry. He mined material from a sandstone quarry at the back of his property, Lawson says.

His work laid the foundations of some of the city’s landmark buildings, including the Rayen School (today, the Youngstown Board of Education building), the first courthouse, banks and churches.

“He made a big difference in Youngstown,” Jones says. “If there was any racial injustice, he would arrange a town hall meeting” to address the issues.

Boggess felt most comfortable in the company of other Civil War veterans. “He was a charter member of Tod Post 29, a local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic that was racially integrated from the very start,” Jones says.

Tod Post 29 served as a template for early civil rights ideals and was well ahead of its time, Jones says. “They didn’t care what color you were or what you looked like,” he says. “You served. You fought. And you belonged.”

Such bi-racial fraternity was rare during the 19th and early 20th centuries, Jones says.

On one occasion, when a local hotel refused service to one of its Black members, White veterans from Tod Post 29 banded together and threatened to boycott its business, he says.

“That post even helped one man who fought for the Confederacy and had his leg amputated. The veterans raised enough money to provide him with a wooden leg,” he says. That soldier is among a handful of Confederate soldiers buried in Oak Hill Cemetery.

Boggess continued to work and live in Youngstown and serve as a prominent member of the community, Jones says. He became active in civic organizations and was a co-founder of the Oak Hill Avenue African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first Black religious congregation in the city.

The Boggess home, then at 464 Edwards St., hosted the first services of the church beginning in 1870.

Boggess died on Aug. 20, 1907, at age 74. He was buried at Oak Hill Cemetery with full military honors.

The legacy of the Boggess family survived. The homestead provided enough acreage for additional houses on the property, including one for his daughter, Lilian. In 1907, Lilian and her husband, Cicero Bradshaw, lived at 474 Edwards St..

One month after Oscar Boggess’ death, Lilian gave birth to a boy. The couple named him Myron, not suspecting he would one day play a part in a musical and cultural revolution.

In the MidJuly edition: The rest of the story.

Pictured at top: Steffon Jones stands in front of the historical marker he helped to secure in 2006.