HERMITAGE, Pa. – When the city of Hermitage sewer plant was under a consent order from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection to make improvements and expand, the city turned it into an opportunity and transformed the plant into the region’s first food-to-energy plant.

Hermitage City Manager Gary Hinkson says it was during the design phases that the engineering firm working on the project brought up the idea of having the additional component of breaking down food waste. After much study and consideration, he says, the municipal authority and board of commissioners both approved the addition to the project.

“Obviously, we had no experience at this,” Hinkson says. “Tom [Darby] deserves a lot of the credit. Basically, we are operating on the fly here.”

Darby, the superintendent of the plant, has had to constantly evaluate the project, identify roadblocks and come up with solutions for equipment needs.

“The unique thing about what we do here is we’re a department of the city,” Darby says. “So we’re a municipal government. On the other hand, we’re running a small business by taking the food waste. We’re providing a service to customers.”

Along the way, Darby has become an authority on the food-to-energy process. A graduate of the Youngstown College of Business in architectural design, Darby received his civil engineering degree from Penn State. After working at an engineering consulting firm, he became manager of the Hermitage Sewer Authority in 1985 and superintendent in 1998.

The investments made in the Hermitage plant have been evolving over time with one idea leading to the next, Darby says.

The food waste co-digestion plant, completed in 2014, required a $32 million upgrade. Originally, the plant was able to handle just fats, oil and grease, along with processed food byproducts.

Then a $1.5 million food waste receiving station was added for depackaging. Most recently, the plant added a storage tank so 100,000 cubic feet of methane gas is readily available should the plant experience a power outage.

NO NORMAL PLANT

In addition to handling municipal sewage for 16,000 residents of Hermitage and the surrounding area, the plant collects more than 500 tons of otherwise unusable food products monthly and processes it. All wastewater plants produce some methane. With this technology though, the plant produces more.

“Our goal was to increase methane production so that we could use that to operate biogas generators,” Darby says. “They take that methane gas and create electricity.”

To reach that end, the plant regularly receives between 60 and 100 tons of food per week, according to a study done by the Water Research Foundation, processing about 10,000 gallons of food waste through the plant’s food digester each day.

“We’re working with private companies from all over – not just Hermitage,” Darby says, noting products have arrived from Columbus, West Virginia, New Jersey, Boston and upstate New York.

Food products entering the plant could be expired, recalled or overstocked items. Darby works with brokers who have these food items and are looking to negotiate a place for them to go. Semi-trucks bring pallets of food to the plant, where it is stored until processing.

About 70% of the food product must be removed from its packaging. The plant has invested in machines capable of perforating cans or cutting openings in the packaging then using centrifugal force to remove the contents. The food is processed into a slurry that can be mixed with the wastewater and processed into methane gas. The biogas powers an engine to create electricity.

Capable of creating enough electricity to offset the needs of the plant, Darby says the power company keeps track of what the plant is returning to the grid. If he overproduces, Darby can send the credit to any city-owned facility within two miles of the plant, which includes five of the city’s wastewater pump centers and the eCenter@LindenPointe.

INVESTMENTS PAY OFF

With the electricity to power the plant previously costing Hermitage between $25,000 and $30,000 per month, the new average monthly electric bill has dropped to $5,000 per month in unavoidable distribution fees, according to the Water Research Foundation.

Hinkson says the plant saves the city additional money by using the sludge, instead of hauling the byproducts away to a landfill.

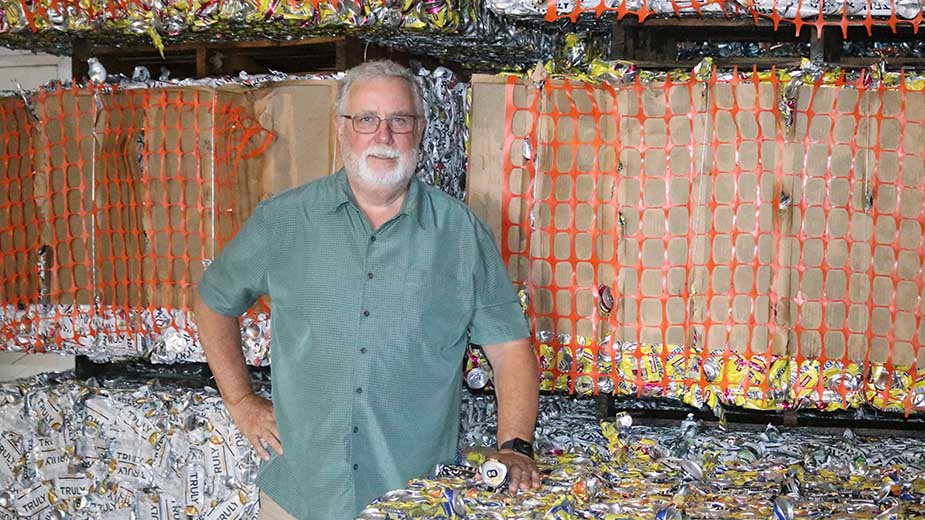

However, Darby says the plant has other ways of generating money, including tipping fees for accepting the food waste, selling wooden pallets and recycling the aluminum and cardboard. Aluminum recycling alone has netted the plant $38,000 in the first half of 2022.

“That’s the side stream part of it that was unintended, but we need to get rid of it and why pay someone, especially for the aluminum,” Darby says.

The plant once accepted about 2,000 55-gallon drums of a honey product, which did not meet U.S. standards and was intercepted by the federal government at several ports coming into the country from China. Darby says the product crystalized, which meant they could not pour it out as he initially thought.

From a labor perspective it became more intensive as the employees had to cut the tops off, pull two sides down and beat the hardened fake honey up with shovels and hoes to get it into the system.

Darby says the substance did make a lot of energy. It was mostly rice and corn syrups with only a small percentage of honey. But the money from that transaction came mostly from recycling the barrels, with the plant netting $8,000 just for recycling the steel drums.

“That was a sticky mess, literally,” Darby says.

As the Hermitage Food to Energy plant has grown, so has Darby’s national profile.

The plant superintendent has become a speaker on the topic, talking on energy neutrality twice in Denmark, as well as making presentations at the WasteExpo in Las Vegas, the Mid-Atlantic Biosolids Association Conference in Baltimore, before the Solid Waste Association in Harrisburg, and the Water Environment Federation Residual and Biosolids Conference in Phoenix. Darby will be presenting a workshop on the topic in New Orleans in October.

Jon Koch, director of the Water and Resource Recovery Facility in Muscatine, Iowa, says he heard about this technology while at a biogas conference in San Diego and wanted to visit a nearby plant using the Scott Turbo separater he saw being used by a food bank there. He was surprised to learn Hermitage, Pa., was the closest municipal plant to him.

Muscatine is a city of about 24,000 along the Mississippi River that it’s close to numerous food manufacturers suitable for creating energy.

About four years ago, Koch met with Darby and took a tour of the Hermitage plant. He says he learned a lot from Darby’s earlier experience, including that he would need three loading docks and a storage area.

“It was nice to have that kind of model,” Koch says. “There was no model for this … this thing was completely new and we didn’t have any idea what we were doing.”

The city created the Muscatine Area Resource Recovery for Vehicles and Energy Program to collect solid food waste and turn it into biogas.

Initially, Koch says, city leaders were exploring converting their gas into compressed natural gas, which could run CNG vehicles. However, now that vehicle manufacturers are leaning more toward electric cars, Koch says they are continuing to explore other uses for the energy they can produce.

For instance, using micro grid technology, he says, they could charge batteries with electricity produced and level out their power, which is susceptible to brownouts and power surges.

Besides aiming to gain renewable energy credits, Muscatine is considering injecting the CNG into a nearby natural gas pipeline. To finance the next technology needed to continue the process, Koch says the city is hoping to obtain private partnerships.

Muscatine’s plant is now considered a pioneer in its area and Koch has gotten visits from officials in Chicago and Minneapolis wanting to learn more.

The project continues to evolve and so does the plant in Hermitage.

“We’re very pleased with how far we’ve come with it, but also excited about the possibilities into the future,” Hinkson says.

Pictured at top: Thomas Darby, superintendent of the Hermitage Food Waste to Energy and Wastewater Reclamation Facility, stands with some of the crushed aluminum recycling bales weighing more than 400 pounds.