To allow faculty and students to return safely to colleges and universities for the fall semester, substantial changes to the form and function of campuses had to be made.

The Business Journal spoke with representatives from regional campuses to learn how they prepared for the semester.

Youngstown State University is adapting to a projected double-digit decline in enrollment and is keeping a close eye on COVID-19 cases, as a second forced closure by the state could significantly affect its annual revenue.

Westminster College and Thiel College, two private colleges in western Pennsylvania, don’t expect much change to their overall student populations, but were forced to get creative with regard to on-campus housing for their smaller student populations.

YSU Eyes Enrollment Shortfall

In July, Youngstown State University got some good news. The projected 20% reduction in state funding it had planned for was revised by the Ohio Department of Higher Education to 6.7%.

Instead of working with a nearly $9 million cut in state funds, the university is facing a $3 million cut, says Neal McNally, vice president for finance and business operations. Still, the university is waiting to see how things shake out in the fall.

Enrollment shortfalls and a possible return to remote learning remain top concerns, McNally says. And while enrollment may not dip to the originally projected 15% decline year-over-year, it will likely still be down double digits, he says.

Driving that decline are more students taking a gap year. Incoming freshmen and current college students are reportedly looking to take a semester or entire year off until the coronavirus pandemic starts to wane, McNally says.

“Enrollment is our biggest budget variable and it’s something we’re paying close attention to,” he says.

Students who live in the region but attend school elsewhere might consider enrolling at YSU for a year to stay close to home, he says. To attract those students, the YSU Foundation increased its annual $8 million scholarship commitment by $1.4 million, with those funds specifically earmarked for transfer students, he says.

Even with the transfer students, YSU still expects to see a decline in enrollment, McNally says.

Projected enrollment shortfalls before the state revised its funding cuts led YSU to lay off 52 staff in June, reducing its $157.9 million operating budget by $26.1 million. Some of the staff were eligible for retirement and chose that, McNally says.

Since then, two or three staff have been recalled and the university created four new student success coordinator positions.

However, the cuts will be disruptive for the fall, says Mark Vopat, spokesman for the YSU chapter of the Ohio Education Association.

Vopat, a philosophy professor, says after the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences merged with the Beeghly College of Education his department no longer has an administrative assistant.

Students will have to go elsewhere for tasks the administrative assistant would normally handle and departments will rely on student workers not permitted to do certain jobs, Vopat says. Those tasks now fall solely on those instructors.

And while the university “has every right to organize the colleges,” faculty weren’t consulted when the decisions were made, Vopat says. There are concerns about how the reorganization and layoffs may affect student success in the fall, he says.

In July, 97% of YSU-OEA members voted to authorize union leadership to issue a 10-day “notice to strike” should contract negotiations stall. The union had concerns about negotiating during a pandemic, particularly because of the changing information from the state.

“There’s no good way to negotiate when you don’t have accurate numbers,” he says. “Hopefully, with revised numbers, we can come to an equitable agreement.”

At press time, the impartial fact-finder had yet to issue her report. In a statement following the union’s notice, YSU said it is “again reassuring students and the community that it is working hard to ensure fall semester classes will be held without interruption starting Aug. 17.”

The possibility of a return to remote learning is also a concern, McNally says. Currently, a third of YSU classes in the fall will be in-class only, a third online-only and the remainder a hybrid. Some of the courses, particularly those with labs, require in-class training, he says.

Another campus closing would also require YSU to send home its on-campus residents and issue refunds.

The university has projected a $1.4 million loss in room and board revenue this year, about an 11% decline, McNally says.

If YSU has to shut down again, it could lose $5.3 million in housing, as well as another $1.5 million in parking fees.

“And there’s no guarantee there would be another Cares Act or federal assistance to help offset that,” he says.

Making the transition from an in-class curriculum to online is “a substantial undertaking,” Vopat says, particularly for upper division courses centered on discussion.

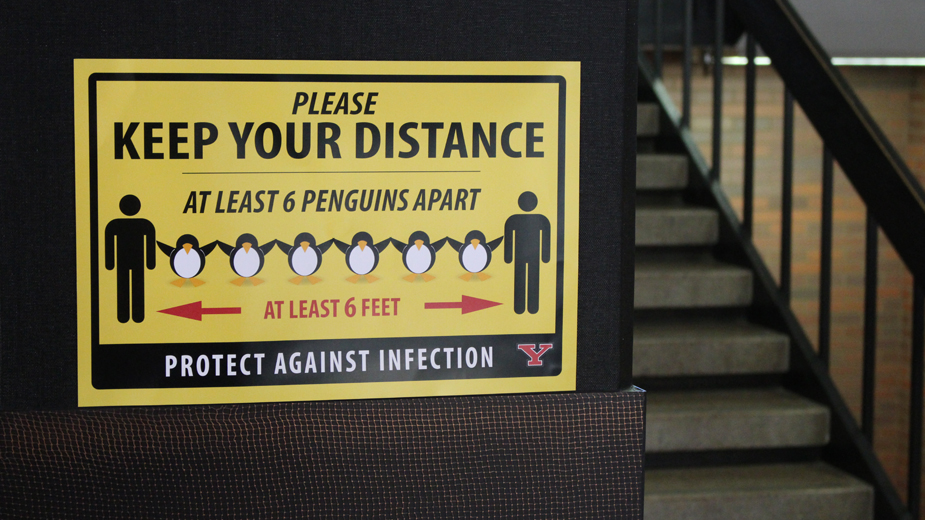

More concerning, however, are health and safety. Issues such as classroom ventilation, cleaning rooms after class, ensuring masks are worn properly and social distancing in hallways are all concerns, he says.

“The university’s efforts have been good as far as hand sanitation and hand-washing stations. But there’s a lot of uncertainty about how this will be pulled off as you bring several thousand students to campus,” Vopat says.

In a survey of 70 college and university leaders about the upcoming semester, a Washington, D.C.,-based education services and research firm, EAB, found administrators expressed “widespread concern” about students, especially undergraduates, socially distancing.

Of those surveyed, 72% cite students following distancing guidelines as their greatest concern, according to the report. The second-biggest concern is monitoring compliance (57%) followed by students abiding by safety measures while off campus (52%).

YSU received $3.9 million in Cares Act funding to finance health and safety measures, such as hand-washing stations, classroom sanitation services, Plexiglass barriers, student welcome/safety kits, quarantine spaces, testing and contact tracing, Wi-Fi upgrades, laptops and other mobile information technology equipment, he says.

Most of the big ticket expenditures were related to technology for remote or digital instruction, he says.

“We are taking steps to really strengthen YSU’s technology infrastructures,” McNally says. “As a result [of the health and safety purchases], YSU will be an extremely safe campus for students and faculty and visitors to come and visit. And we’ll have better IT as a result of it.”

Westminster Begins Class Two Weeks Early

Westminster College is reopening for in-person classes and on-campus living for the fall semester – and it’s doing it two weeks earlier than usual.

The private liberal arts college in New Wilmington, Pa., will forego its midterm and Thanksgiving breaks, ensuring students wrap up the semester without having to leave campus and return, says Gina Vance, vice president of student affairs and dean of students.

“The idea there is to bring students in and to minimize large comings and goings so we minimize the travel on and off campus, which might increase the likelihood that we pass around the virus,” Vance says.

As part of the reopening plan, students are asked to remain in the nearby area once the semester begins.

The early start creates some challenges with curriculum, Vance says. Faculty have two fewer weeks to plan and prepare for a blended model of on-campus and virtual learning. In the classroom, teachers will have to accommodate six feet of social distance, inhibiting small-group work.

Westminster faculty already have experience with online learning, using programs such as Google Classroom, to augment the in-person environment, Vance says.

“We learned a lot in March, April and May when we had to move to virtual learning very quickly,” she says.

Currently, Westminster expects 2% to 5% of its students will choose virtual learning, she says. The rest have opted for in-class learning, which required the college to examine its on-campus residences.

For fall semester, there are 40% more private rooms arranged for students than a typical year, Vance says. Residences can accommodate a larger student population than the typical average of 1,200. During the summer, the college did a predictive assessment based on its housing stock and anticipated enrollment, she says.

Westminster expects an incoming class of about 315 this semester, which is more than last year, she says, and the retention rate is around 80%.

To mitigate spread in confined living situations, Westminster created so-called “family pods,” in which a group of student rooms are arranged around a shared bathroom. Pod-style living provides a respite for students where they can relax and take off their masks, which are required everywhere else on campus, she says. Bathroom fixtures will also be assigned to the same students.

“The family pod model is something we learned from our professional circles and brought it back here and made it work for us,” Vance says. “We needed to take into consideration bathroom use and how to keep students safe, but also provide a community feel while they’re here.”

Students are permitted to use only the bathrooms to which they are assigned, Vance says. As for enforcing that rule, the college is “really relying on our students and faculty and staff to do what we always do, which is care for one another,” she says.

Additional measures were taken to make common areas less dense, including the food court in the Titan Union Building. Sodexo Campus Services is setting up three ordering kiosks for Starbucks and Sammies products. An online ordering system is also being established to alleviate congestion in the food court.

“It will be less active than we would typically see,” Vance says.

Thiel Adds Health Screens to Daily Routine

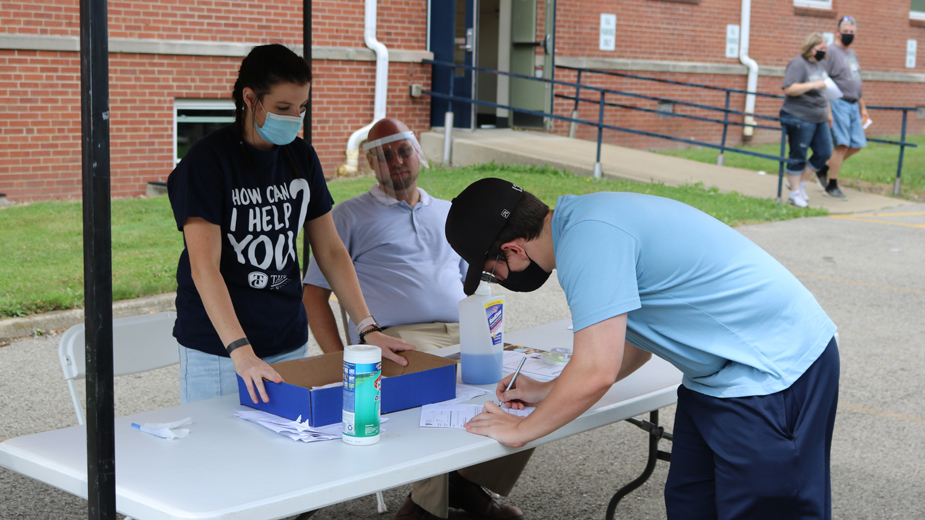

Students and faculty returning to campus at Thiel College need to arrive early to allow time to go through screening stations before being admitted inside the main classroom building.

After a temperature check and questionnaire, each individual who passes will be given a color-coded bracelet that grants access to areas throughout the day. Screening stations are located throughout the campus and will be staffed based on the daily amount of foot traffic those areas receive, says Mike McKinney, vice president for student life and dean of students.

“We’ve been doing this over the summer with our employees,” McKinney says. “So we’ve had some practice in working out the kinks.”

Thiel has also removed excess furniture to accommodate occupancy levels and added six-foot spaces where applicable, directional signage and hand sanitizer stations, he says. The college is requiring physical distancing as much as possible.

“We’ve reconfigured classrooms, common areas, recreation spaces and other facilities in order to achieve that,” he says. Some larger spaces on campus are being repurposed for classroom space.

Over the summer, Thiel had its faculty prepare for remote instruction, although just 10% off its classes will be offered solely online, McKinney says. If a faculty member isn’t comfortable teaching in person, if students are concerned for their health or has special circumstances, they can apply for online coursework.

The training will also ensure a smooth transition should the college again be forced to close amid the coronavirus pandemic, he notes. Few faculty have requested to teach online and Thiel anticipates most students will return to campus.

“We’re actually on pace to meet or exceed incoming student numbers,” he says. “Returning student numbers are looking real good too.”

For its on-campus residents, Thiel is spacing out students to every other room and working with a nearby hotel to provide some housing as well, McKinney says. Typically, about 85% of the college’s student population lives on campus, but this year it’s just shy of 80%, so there will be enough room to space out residents.

“We’re estimating we’ll be below 70% of total beds on campus,” he says.

Pictured: Sign urges social distancing in DeBartolo Hall at Youngstown State University.