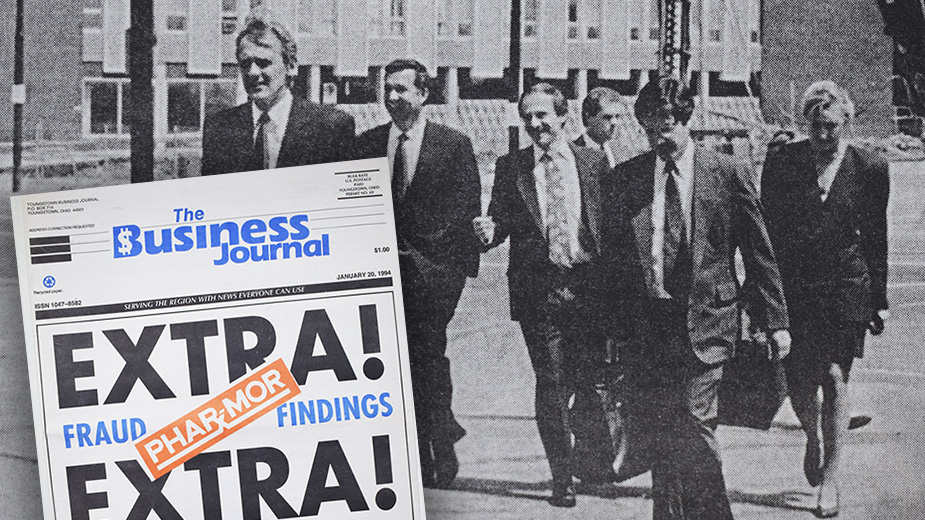

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – The “Extra” edition of The Business Journal dated Jan. 20, 1994, represents the first and only time that the newspaper has released an edition outside its normal publication schedule.

The contents of the “extra,” which contained no paid advertising, more than warranted the treatment. It offered a word-for-word printing of the federal examiner’s summary of the investigation into Phar-Mor Inc., including charts detailing the relationships between the many players and entities.

U.S. Trustee Scott Michel requested the hiring of an examiner as part of the Chapter 11 bankruptcy that Phar-Mor filed Aug. 17, 1992, mere weeks after it had ousted president and co-founder Michael I. “Mickey” Monus, who initially was accused of masterminding a $350 million fraud and embezzlement scheme.

Phar-Mor executives subsequently would raise that figure to $499 million, and federal prosecutors much later put the total at $1.1 billion, including bank loans and stock purchases made based on false financial statements. The examiner’s revelations of how the company grew to 300 stores and annual revenues of $3 billion were stunning.

The report would prove to be no idle examination of business failure. Producing evidence that might otherwise have gone unrevealed, the report reactivated the criminal probe into the activity of Phar-Mor’s principals, including Nathan Monus, father of the deposed Phar-Mor co-founder. In addition to being aware of the fraud taking place at Phar-Mor and keeping silent, the report found that Nathan Monus benefited from related-party transactions that weren’t disclosed to Phar-Mor’s board of directors.

“The investigation is continuing. I can’t say anything more,” John Sammon, assistant U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Ohio, said in our February 1994 edition that followed the release of the examiner’s report. Sammon was the lead prosecutor in Mickey Monus’ then-approaching trial.

The summary of the 1,000-page report laid bare the flawed and shoddy business practices within Phar-Mor that appeared to doom the deep-discount retailer almost from the start. It also exposed the people who were unwilling to upset the gravy train and ignored huge red flags. The report was prepared by Jay Alix & Associates, the federal examiner appointed by U.S. Judge William T. Bodoh, who was overseeing Phar-Mor’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy in Youngstown.

Perhaps the most surprising element of the report was the revelation of what triggered the internal investigation that led to the demotion (and later firing) of Monus. According to the summary, it was none other than real estate icon and Phar-Mor stockholder Edward J. DeBartolo Sr. who tipped off company officials about a check improperly paid to a travel agency on behalf of the World Basketball League, a professional sports enterprise Monus founded.

The tip and the discovery of the $80,000 check to the travel agency “led Phar-Mor’s board to investigate further, thereby discovering the fraud,” according to the report.

The federal examiner detailed how Phar-Mor operated from the beginning, highlighting such early flaws as inadequate management information systems and spending controls. Instead of developing MIS of its own, Phar-Mor used systems owned by Giant Eagle Inc., the Pittsburgh grocery store chain that initially operated Phar-Mor as a division and later a subsidiary before being spun off. Giant Eagle principals, including CEO David Shapira who also held that title with Phar-Mor, maintained ownership stakes.

“The borrowed computer programs were not designed for Phar-Mor’s business and, even after some customizing, were not adequate for Phar-Mor’s needs,” the report stated. Additionally, Phar-Mor was slow to implement point-of-sale scanning, exerted “loose controls over non-construction capital expenditures” and maintained inadequate internal controls for cash disbursements.

Significantly, it used a supply of blank checks (referred to as “typed checks”) on two bank accounts, from which it made disbursements, thus circumventing the normal accounts payable auditing and approval system and computer processing. This enabled advances from Phar-Mor to be made to WBL and the Youngstown Pride basketball team, among other irregular payments.

Other issues identified in the report were concerns over the lack of experience possessed by senior management and board members and about Monus’ increasing “distractions.”

According to Pat Finn, Phar-Mor chief financial officer from 1988 to 1992, the “management” of the accounting fraud that led to its collapse started in 1984, shortly after he had been hired – although it would not have any material effect on the company’s reported net profits until later. During the 1985 and 1986 fiscal years, Finn said, Monus directed him “to understate certain expenses reflected on Phar-Mor’s monthly income statements to conform to budgeted amounts.”

The inflation of store inventory started to materially affect financial results in fiscal 1988 and would do so through January 1992, according to the examiner’s report. Finn’s manipulations would include altering gross profit margins to keep them near what was budgeted. As Phar-Mor’s actual losses increased, he began manipulating income statements to conceal the fraud.

“You knew you were doing something wrong but you never understood how wrong,” Finn said in a November 1994 PBS Frontline documentary.

Although there weren’t “two sets of books” in a comprehensive sense, the amount by which accounts were misstated were tracked in a database that came to be known as the “subledger.” The accounting department would prepare two gross profit margin reports, with the one containing false data sent to David Shapira.

On one occasion in 1990, the report containing the actual data was inadvertently sent to Shapira, who summoned Finn to explain the low gross margins it revealed. Finn told him the report was a preliminary one, an explanation Shapira reportedly accepted.

Shapira subsequently said he didn’t recall the incident, according to the examiner’s report.

Factors that helped to conceal the fraud were the involvement of several members of management, lack of coordination and minimal internal controls of accounting and management systems. Cash receipts from exclusivity agreements and reimbursements for construction costs also were used to reduce the extent of misstatements over years.

The report also disclosed Phar-Mor would withhold checks cut to vendors when it didn’t have cash available to cover them, although the amounts were often understated in reports to David Shapira. A March 1991 report to Shapira by Finn falsely started that the total amount of held checks was only $96 million, when in reality it was $156 million. Vendors began withholding shipments to Phar-Mor in response to the delayed payments.

Of particular note is a document that nearly went undisclosed and became the subject of a legal battle after Alix submitted its draft report in August 1993. The May 31, 1991, memo from Phar-Mor general counsel Charity Imbrie to Shapira and his brother, outside counsel Daniel Shapira, outlined “concerns” that Imbrie and others had about Phar-Mor and Monus.

The issues detailed in the memo – which was circulated about a month before Corporate Partners agreed to invest $200 million in Phar-Mor – included concerns expressed by Phar-Mor employees about a cash flow crisis in February and March 1991, the use of Phar-Mor employees for noncompany business and Monus’s diminished attention to Phar-Mor. Shapira, who consistently maintained he had not been aware of the fraud taking place at the company until July 1992, ordered Imbrie to destroy all copies of the memo, although would retain a copy on the advice of counsel.

Phar-Mor fought production of the memo in the fall of 1993, claiming attorney-client privilege. Ultimately the company was ordered to turn the memo over after failed attempts to appeal Bodoh’s order and to strike the examiner’s bid to hold the company in contempt.

“I said in my order [approving the appointment of an examiner] that given the high-profile nature of the Phar-Mor case and the number of persons who have been hurt, there is an overriding public interest to be served by a full and complete investigation of the allegations of wrongdoing – and I think it is doubly true now that I have read Jay Alix’s report,” Bodoh told The Business Journal in early 1994.

Those sentiments were echoed in the February 1994 Business Journal editorial. The primary reason for publishing the Jan. 20 Extra edition “was that the business community – not to mention the many people whose jobs have been lost as a consequence of the Phar-Mor fallout – has a right to know how and why the walls came tumbling down.”

Pictured at top: Lawyers and company executives such as New York City turnaround expert Antonio Alvarez (second form left), appointed Phar-Mor CEO in the wake of the scandal, frequently appeared in U.S. Bankruptcy Court.