SPRINGFIELD TOWNSHIP, Ohio – A crossroads in northeastern Beaver Township in Mahoning County couldn’t appear more sublime today.

Regal houses and estates dot the neighborhood along Calla Road as it runs eastward across state Route 164 and into nearby Springfield Township, sweeping toward Evans Lake. Just to the south is the entrance to one of Mahoning County’s most elegant clubs, The Lake Club, where patrons spend time golfing, swimming and dining.

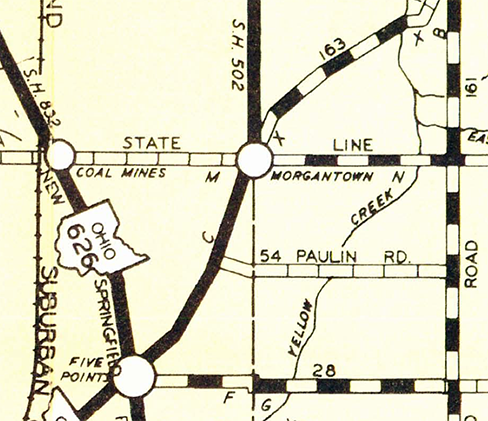

Not so 150 years ago. During the mid-19th century, this was coal country – a part of rural Mahoning County that lured workers who toughed it out in the local mines. By the 1860s, this corner of Beaver Township had earned an unusual name: “Morgantown.”

The name is unusual because it’s not in reference to a family or landowner who lived at or near the intersection of Calla Road and state Route 164 during the formative days of the Mahoning Valley.

Indeed, Morgantown has a much more notorious origin and a legacy filled with corruption, intimidation, larceny and arson.

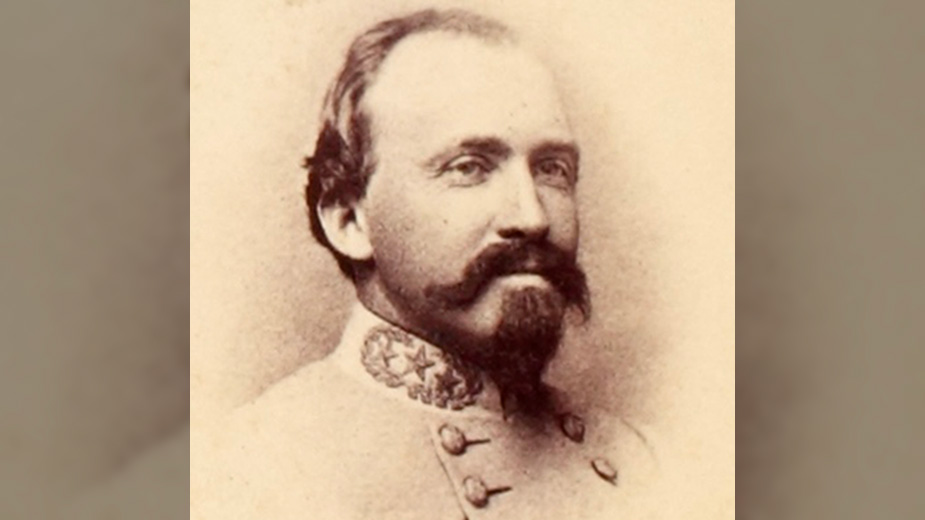

It begins in 1863, as Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan and his Confederate raiders swept into Ohio, terrorizing communities throughout the summer until his surrender on July 26 near West Point in Columbiana County.

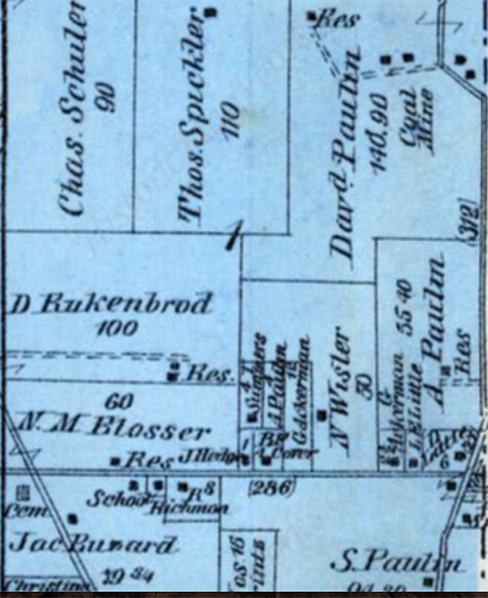

According to Gen. Thomas Sanderson, editor of the “20th Century History of Youngstown and Mahoning County, Ohio and Representative Citizens,” a handful of locals led by Azariah Paulin, then a prosperous mine owner and farmer, expressed sympathies for the Southern cause – more commonly referred to as “Copperheads” in the North.

As news of Morgan’s invasion reached Mahoning County, a group of farmers mobilized to help intercept the raiders. As they made their way south, words were exchanged as the group passed Paulin’s property.

On the return trip, the group found that Paulin’s land had been fenced in with a sign outside declaring the site “Morgantown.” The name stuck, as did the bitter feelings between residents in this corner of Beaver Township.

Following the Civil War, Paulin, along with his relatives and friends who lived at Morgantown, launched a 20-year campaign of retaliation and intimidation against neighboring farms, mines and other interests.

“Their differences with their loyal neighbors brought on acts of aggression and retaliation that finally degenerated into the midnight crimes that for a time gave the township of Beaver an unsavory reputation,” according to Sanderson. Paulin, possibly affected by the economic depression of the 1870s, turned to crime as a means to augment his income.

OUTLAWS AND UNTOUCHABLES

The “Morgantown Gang” – described by Sanderson as a “small but well-organized lawless element” – evaded prosecution for two decades. During this period, Paulin and his sons helped to orchestrate raids on competing farms and mines and threatened those who would testify against them. The gang “succeeded for 20 years in terrorizing a large part of the community by crimes of arson, theft and perjury, until the reign of terror was brought to an end by the arrest and conviction of some of the ring leaders.”

Accounts of sugar camps destroyed, barns and houses torched, sheep, hogs and horses stolen, and outright fraud were pervasive throughout this period. All were connected with the Morgantown Gang.

On one occasion, Morgantown associates allegedly burned the tipple of a rival coalmine. The mine owner, Joshua Heindel, rebuilt the structure but it was torched again. After Heindel began construction a third time, someone fired a bullet into his house. Heindel and his wife fled Morgantown for good.

Securing convictions proved problematic for law enforcement, according to Sanderson.

Paulin, known as the “Old Fox” for his “cunning and astuteness,” stood as the gang’s de facto leader, applying pressure on anyone who dared challenge the outlaws.

“So well organized were these lawbreakers that for a long time, though they were well known, few could summon up courage to proceed against them,” Sanderson’s book recounts. Those who did risked “the vengeance of the conspirators.”

In one instance, a German farmer who was called to the stand in a case against a Morgantown Gang member declined to testify, saying that he “didn’t want to have his barn burned.”

Even an attempt by area farmers to quash the disorder by hiring a local detective came up empty. According to an account in the Mahoning Dispatch in January 1884, W.H. Triplit of the Eureka Detective Agency proved as dishonest and corrupt as the men he was supposedly targeting.

Instead of persecuting Paulin and his outlaws – Triplit was paid a handsome sum of $2,500 by farmers to do so – the sleazy detective used the opportunity to encourage the gang’s crime spree.

Alas, it was none other than Azariah Paulin who sold the detective out. According to the Dispatch, Paulin said that the detective attempted to persuade members of the Morgantown Gang to break into the Clinker House, a North Lima inn, and steal a set of harnesses. According to Paulin, the detective was guilty of “other grave works.”

THE SNITCH

By the 1880s, however, the gang’s luck began to run out. Relentless press coverage, backed with a collective response by Beaver Township residents and a renewed push to prosecute these outlaws, ultimately resulted in their capture and imprisonment.

Among the more detailed accounts of the gang are found in the Dispatch, a weekly publication that was then printed out of a small operation at East Main and Broad Street in Canfield. In 1893, the Dispatch was moved to a new location along Broad Street. The newspaper ceased publication in 1968 but the building still stands.

Through the mid-1880s, the Dispatch closely followed the gang’s movements, who were now under close scrutiny by law enforcement. In 1883, several Morgantown gang members, including Azariah’s sons and a nephew, disrupted a gathering in North Lima, brandishing knives and pistols and assaulting several attendees. The members were arrested but committed perjury when they stood trial.

Shortly thereafter, gang member William Cluse set fire to the barn of Noah Blosser to intimidate him from testifying against his fellow Morgantown crew in the “North Lima riot” case. Cluse, armed with a .22 caliber revolver, was found hiding in a coalhouse near his home. He was arrested in January 1884 on the charge of perjury, an arrest that probably saved his life.

“The citizens of Beaver Township had procured a rope, and had the sheriff not made the arrest and run the prisoner off in his sleigh, there might have been a neck-tie social,” a euphemism for a lynching, the Dispatch account reads.

Despite boasting there “were not enough constables in town to take me,” Cluse began to cooperate with authorities. “Billy Cluse seems to have it in for his ‘Morgantown gang,’” said an ominous Dispatch item. “The gang will have it in for him later.”

Cluse, accompanied by Sheriff Lodwick and a penitentiary guard, guided authorities to the scenes of many of the gang’s crimes over the past three years, mostly visiting sites the group plundered. “Wm. Cluse, one of the ‘Morgantown gang,’ is giving the party away in great shape,” a Dispatch account reads.

There soon followed a rash of indictments. Azariah’s son, George, and his nephew, Francis Paulin, were picked up in Tuscarawas County where they were working under fictitious names. Gang member Delmar Little received six years in prison but served only two. Others were rounded up as well.

But what became of Azariah Paulin, Morgantown’s patriarch?

ON THE TRAIL OF THE ‘OLD FOX’

Paulin was indicted on four charges: concealing stolen property, corrupting witnesses, perjury and arson – all of them based on the cooperation of Cluse. Paulin was arrested in June 1884, after being found under a bed and prevented from making a run for it before the sheriff’s arrival, according to a Dispatch account.

“It is now thought the prisoner intended to start for Canada the same night he was arrested,” the newspaper reported, “but he failed to start early enough, and therefore he is now wiping the sweat from his brow, behind the bars in county jail.”

Nevertheless, Paulin secured a $2,200 bail bond by mortgaging his 96-acre farm. Then, he disappeared.

Paulin – thought by his wife to threaten suicide – evaded the law for some two months, moving from place to place almost daily. Authorities caught track of him heading eastbound on the Cumberland Railway. While stopping over in Harrisburg, the “Old Fox” posed as a tramp under an assumed name to secure free overnight lodging in a local lockup there. He was released the next morning.

Paulin took the Cumberland to Shippensburg, Pa., where he lodged with Jacob Stoffer, a former resident of Mahoning County.

The law wasn’t far behind.

On the alert for the fugitive, an astute sheriff in Shippensburg discovered that Paulin had received mail at the local post office. As the sheriff left the building, he observed Paulin on a horse across the street. He closed in and immediately took him into custody. Paulin had between $7 and $8 on his person.

“In court he presented a grizzled and unkempt appearance,” according to Sanderson’s History. Paulin pleaded guilty to two counts: subornation of perjury and arson. The charges of receiving stolen property and corrupting witnesses were dropped.

“I’m not really guilty of this crime, but I discover that I am so surrounded with witnesses who will swear my liberty away and whose statements I cannot contradict, except by myself,” Paulin is quoted in Sanderson’s account. “I am satisfied that upon trial I would be found guilty, although I am perfectly innocent of the charge.”

His attorney, I.A. Justice, pleaded the court for clemency, citing the defendant’s age and health. Paulin was sentenced to six years in prison, three years for each count. He served 41/2 years and was released in 1889 for good behavior. He returned to Mahoning County and died in Beaver Township in 1905 at the age of 75.

There is little or no evidence left of Morgantown. Aside from a 1939 highway map that references the hamlet, the name faded years ago.

One reminder, however, still survives as motorists cross into Springfield Township and divert down a roadway that winds toward the entrance of the Lake Club.

Its name? Paulin Road.

Pictured: Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan and his Confederate raiders terrorized Ohio in 1863.