KENT, Ohio – As small-business owners get older and rethink their futures, as well as the prospects for the companies they spent lifetimes building, the Ohio Employee Ownership Center at Kent State University can start them on a path toward retirement.

The center works with business owners considering succession plans, including those seeking answers on matters such as how to begin the transition to employee ownership.

Chris Cooper, the director of the center, says the business succession program was developed in about 1995, as it realized how many businesses were not properly planning for the transitions. The program has further grown through the years, leading to programs presented in 12 states and three countries.

“We always encourage business owners to think of succession planning as part of their business planning,” Cooper says. “So if you are developing any type of strategic plan for your business, how you’re going to exit that business should be a part of that.”

It is not only about the planned slow transition, Cooper says, but also developing a contingency plan should something unexpected happen. Too many business owners, however, are too busy running their businesses to begin the process, which Cooper believes should start early – in their 40s or 50s – even if they plan to work into their 70s.

“If you enjoy what you’re doing, there’s no reason for you to stop doing it. Just understand that it doesn’t mean you don’t have to plan,” Cooper says.

The project coordinator at the center, Michael Palmieri, says statistics show only about 25% of business owners have a succession plan. Yet business owners are growing older and baby boomers own nearly half of small businesses.

For some, the difficulty in getting started could be one’s personal identity is so strongly connected to being the owner for so long. For others, it’s not knowing where to begin.

The ownership center provides a business succession planning manual, available on its website or by calling its staff, which can help small-business owners decide which succession option is best. There are several options, including selling the business, succession to a family member, developing a group of successors from inside the organization and employee ownership.

Many times, Cooper says, family members are unavailable or uninterested because the success of that business gave them an opportunity to try their wings and build their own careers. Their connection to a business was tangential the past 15 or 20 years.

A management succession plan requires a strong team in place, one ready to handle the day-to-day operations, which, Cooper suggests, businesses should strive for anyway, even if the business owner just wants to step back, take a vacation or have peace of mind should something unfortunate happen.

“The idea of a mentorship is a good one,” Cooper says. “Many business owners want to get in there and make all the decisions and do all the important stuff and have all the important relationships with customers, with other folks. It’s really important that they really spread out that responsibility within the business as best they can.”

Selling a business can be profitable but not always possible. Only 20% to 25% of businesses on the market end up being sold.

“Employee ownership is a really cool option because through the various kinds of structures that help a business sell to their employees, the business owner can essentially create the buyer of their business. So it kind of maintains that legacy aspect,” Cooper says. Many business owners, he adds, are uncomfortable selling to an outsider, who may make big changes or might lack anyone in mind to purchase their business. Employee ownership can reward the employees who helped build the company and allow it to remain independent and part of the community.

Employee ownership programs benefit the business owner, Palmieri adds, who gets a fair price for the company, and its employees, who can share in the profits, which can build more wealth for them than employees working in other types of organizations.

Local Employee-owned: Brainard Rivet Co.

Formerly a part of Textron, Brainard Rivet Co. found itself in a tough position when, in 1997, Textron decided to close the plant in Girard. A company that traced its roots nearly 100 years at that time, the Brainard Rivet Co. went from $15 million in annual sales to zero, according to the general manager at Brainard, Joseph Lamanna.

Although Textron was not interested in selling, Lamanna credits then U.S. Rep. James A. Traficant with helping to turn the wheels that led to Brainard being bought in 1998 by Fastener Industries Inc., a Berea-based company, that already had an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) in place.

Brainard Rivet became a subsidiary and adopted its ESOP as well. Lamanna now makes many of the day-to-day decisions, he says, but the large decisions go before the board of directors. Any employee who secures 10 employee signatures can run for a position on the board.

Employees have better benefits than most, according to Lamanna, including the semiannual stock dividends and retirement plan. Wages are competitive, but the real benefit is the company doesn’t make employees pick up any part of their medical, dental and vision insurance, which saves them money.

In addition to stock dividends, the board has voted in recent years to pay 15% of the annual earnings into employee stock options.

Employees also have the option to invest in other retirement plans and receive other benefits, such as an education assistance program.

“It will be 25 years in May, and it has worked out very well for us,” Lamanna says. “I would say most of the people here, if not all, are a lot happier being an ESOP versus what we were before. Our benefits were poor. It’s just a totally different atmosphere. I think people take more pride in their work when they know they are an owner too.”

Beginning the Process

Employees of employee-owned businesses know they have a financial stake in their company. Even if there is a board of directors or CEO, employees know they can have a say and directly benefit from their ideas and labor.

Cooper and Palmieri point out employee ownership is something people on both sides of the political aisle seem to be able to get behind because of the many benefits it can provide for employees.

“We really do see it as a way to help a lot of the economic issues,” Palmieri says. “Dignified work, lower economic inequality, more stability for families and communities – it’s something that a lot of people, regardless of what walk of life they are, see a lot of value in. The idea that people work hard, show up to work, do good work, that they should be rewarded.”

Although Cooper and Palmieri admit employee ownership is one of their favorite options, they will work readily with any business owner interested in learning about any succession planning options and have a list of more than 100 resources and professionals for business owners looking for help to put a plan in place.

Going through the manual and worksheets the center provides, Palmieri points out, can save a business owner time and money rather than doing the research.

“We see quite often that if the business owner doesn’t have a clear sense of what their goals and objectives are, that often something will happen to the process as they are going through it that will derail it and prevent them from actually developing a good, sound succession plan,” Cooper says.

By considering goals and objectives before visiting a professional, business owners have a better focus on what services they need and who can provide them, saving them time and hourly fees.

“That’s one of the things that we pride ourselves on – not doing a cookie-cutter approach, but meeting the business owner where they are,” Palmieri says.

Those looking for more information on where to begin or for upcoming events can go to OEOCKent.org and call the office. The OEOC program has helped to create ESOP’s for more than 100 businesses. Cooper and Palmieri are working now with nine businesses in various stages of succession planning. The succession-planning program is being funded through the Cleveland Foundation in northeastern Ohio.

They are happy to work with those outside that region, answer questions and add new businesses to the email list of upcoming events.

Returning to even more of their prepandemic activities in 2023, they plan to begin to work again with chambers of commerce and economic development groups to put together workshops for those seeking more information.

They generally work with companies with fewer than 50 employees, which may lack the resources to write a succession plan, although they have helped companies with 100 to 150 employees.

“Eighty percent of all small businesses have less than 20 employees. So that’s the vast majority who may not have those resources to put together an effective plan,” Palmieri says.

The center also hosts an annual conference on the most recent developments in support of those who work for an employee-owned small business.

Regulations change, and staying on top of them is crucial as the employee-owned company evolves in the future. Keeping things set up right can lead to better lives and retirements for employee owners down the road.

In 2019, more than $3 billion was paid out to Ohio’s employee owners, a state where there are about 310 companies with an ESOP, Palmieri says.

“It’s incredible,” says Palmieri. “It’s approaching the amount of Social Security paid out for the whole state.”

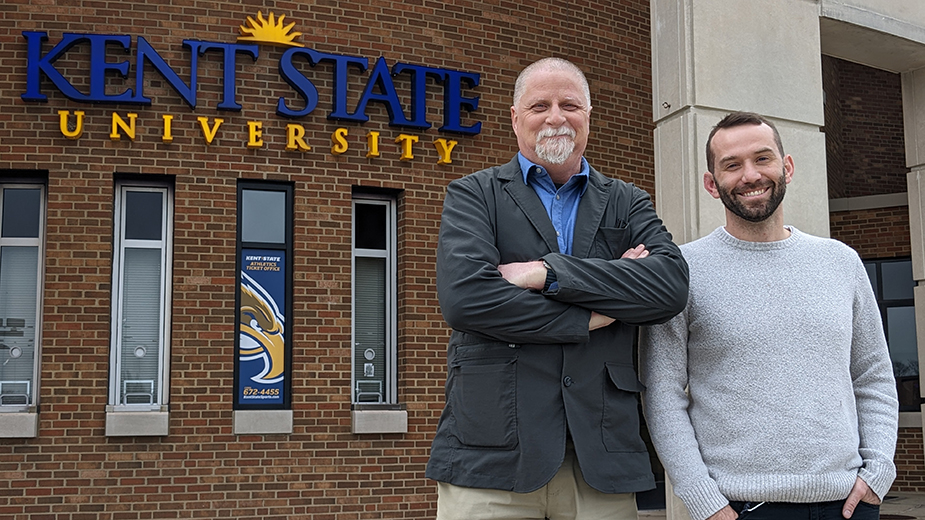

Pictured at top: Director Chris Cooper, left, and Michael Palmieri, project coordinator, lead the Ohio Employee Ownership Center at Kent State University. The center helps small-business owners navigate their options for succession planning.