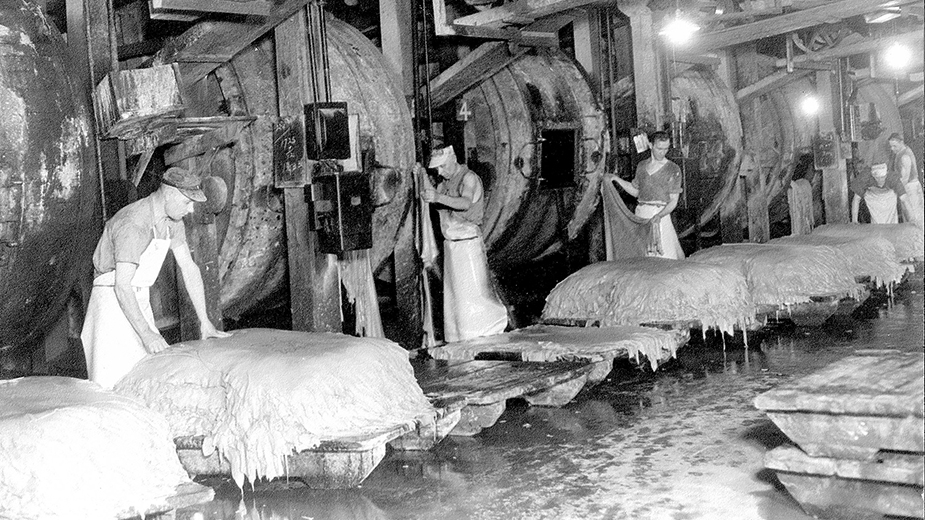

GIRARD, Ohio – The stench was unbearable at times, as slab upon slab of freshly skinned cowhides shipped directly from the Chicago stockyards bled out in a storage cellar at the Ohio Leather Co. in Girard.

For workers during that summer of 1947, the putrid smell was all part of the job. Hundreds of men and women produced leather used to manufacture boots, shoes, belts, straps, gloves and dozens of other accessories for the commercial market as the country adjusted to a peacetime economy after the second world war.

“I worked there that summer as a 16-year-old for 96 cents an hour,” recalls Nicholas Melfi, the father of Girard Mayor James Melfi. “I worked in the pasting department. My job was to sponge the leather down and then push them in a dryer at 140 degrees.”

Melfi, now age 90, worked on the fifth floor so he was spared duties in the cellar where the hides came in. “I never worked down there. But I had friends who did. It was sort of like a slaughterhouse. They removed the hair and treated them down there.” By the time Melfi handled the product, it had already been tanned into leather.

The Ohio Leather Co. was among the most respected leather businesses in the country and the company provided a good living for families, he says. “I was just a kid but people made their careers and livelihoods there. It was a great company.”

Members of Melfi’s extended family were also employed at Ohio Leather, some for more than 40 years. “I had uncles that made a living there. I can’t emphasize enough how much it meant to the city of Girard in the ’30s, ’40s and even the ’50s,” he says.

During World War II, more than 8,000 skins per day moved through the plant, then one of the largest tanneries of its kind and a hallmark of Girard industry since it was founded as the Mahoning Leather Co. in 1899. In the 1930s, the company employed about 700 workers.

The postwar years were not as kind. Business began to suffer during the 1960s as a result of competition from overseas and the lack of modern production methods. By late 1970, the leatherworks ceased operations and officially closed its doors in 1971, leaving nearly 300 without jobs.

Today, little remains of the Ohio Leather Co., more commonly known as the Ohio Leatherworks. Overgrown thickets and trees claim most of the 27-acre site that fronts U.S. 422 to the east and hugs the Mahoning River to the west. Old telegraph poles protrude through the tall brush while remnants of the sewage clarifier of the company remains intact. What was left of the main, red brick factory was demolished years ago after a series of fires.

Left behind was land soaked with toxic waste such as chromium sulfate, a chemical the company had used in its tanning processes since the turn of the 20th century. Other contaminants used in the operation included sodium sulfide, sodium chloride, lime, ammonia salts, sulfuric acid and mercury.

“This was all pre-EPA [U.S. Environmental Protection Agency],” says Melfi’s son, Mayor James Melfi. “So a lot of this stuff was just dumped in the river.”

Now, a half-century since the company closed, the city is poised to take a major step in redeveloping the entire site, plus put into play another 40 acres of adjoining land that Melfi says could transform the community.

The U.S. EPA announced in May that it had awarded the city $500,000 to be used to start the cleanup. The city contributed $100,000 in matching funds toward the project.

“It’s an honor to all of the hard-working citizens who labored there,” the mayor says, emphasizing the early immigrant population the company employed. “This was the place where early immigrants came to work in Girard,” he says.

Girard is one of just 14 sites across the country and two in Ohio to be awarded a federal cleanup grant, Melfi said. The U.S. EPA called the city’s submission “an outstanding application” that demonstrated the legacy of the site and the public need for its redevelopment.

For Mayor Melfi, the award capped more than two decades of fighting to gain control of the land.

“The one thing we knew is that we couldn’t get anything done until we owned the property,” he says. “It took every bit of 24 years to wrestle it from the last owners. It was a nightmare.”

During the 1990s, the property fell into the hands of “unscrupulous owners,” Melfi says, and the city began a protracted effort to acquire the land.

Girard ultimately took possession of the property in 2015, Melfi says. Once it is cleansed, the mayor envisions the site as a mixed-use development that could include office or retail buildings fronting 422 and a park that spreads toward the river. He expects work to begin as soon as possible toward the cleanup effort.

The property has long been an eyesore and a target of revitalization, says Julie Green, director of the Trumbull County Planning Commission.

“This was a huge coordinated effort,” she says, among the city, her agency and the Youngstown/Warren Regional Chamber.

In 2018, the Western Reserve Port Authority helped to secure funding to conduct a Phase II environmental assessment at the site, which identified contaminated “hot” spots on the property.

A draft work plan on the cleanup was submitted and an approved EPA work plan is due July 9. The work must be completed by Sept. 30, 2024.

Once all the deadlines are met, the funding would be made available in October, Green says. She estimates the EPA award plus the matching funds from the city are sufficient to remediate the property and kick-start redevelopment.

Girard had applied for the grant in 2019, but fell short, Green said. “They retooled the application in the fall of 2020 and it was awarded.”

The city contracted with Jason Ketner, a landscape architect from The Ohio State University, who drew renderings of a proposed use for the site. Among them are parking areas, a walking trail and a sloped lawn that would extend to the edge of Squaw Creek, which bisects the land and flows into the Mahoning River.

As the walking trail leaves the Leatherworks site, the preliminary plan envisions a playground, wetlands and an elevated nature observation deck.

Melfi says the Leatherworks site is just one component of a much larger plan that would incorporate the construction of a new bike path that connects the old industrial land with the Lake-to-River Greenway.

Recently, the city settled with the Ohio Central Railroad, resolving litigation that lasted 16 years. The settlement would allow Girard a 99-year lease of up to 40 acres contiguous with the Leatherworks property that extends into Weathersfield Township. The Ohio Central land – aptly termed “Banana Park” – bends about a mile along the river and runs directly behind where the Provence Mills Event Center, Brewster’s Ice Cream and Creekside Mini Golf sit along 422. The land then feeds into the Leatherworks property, the mayor says.

“The most important thing is that there’s no cost to the city. And after 99 years it’s turned over to us,” Melfi says. The measure is now before City Council.

Initially, the Ohio Central wanted to use the land behind the event center – formerly the Golf Dome – for a construction debris landfill, which Melfi opposed. Instead, the city took the short line railroad to court and in June reached a settlement.

“All of this was to be a demolition debris dump – they were pretty close to doing that,” Melfi says as he glances over a panoramic glen populated with wildflowers and redwing blackbirds. “Now, this land is preserved. It would’ve ruined Girard.”

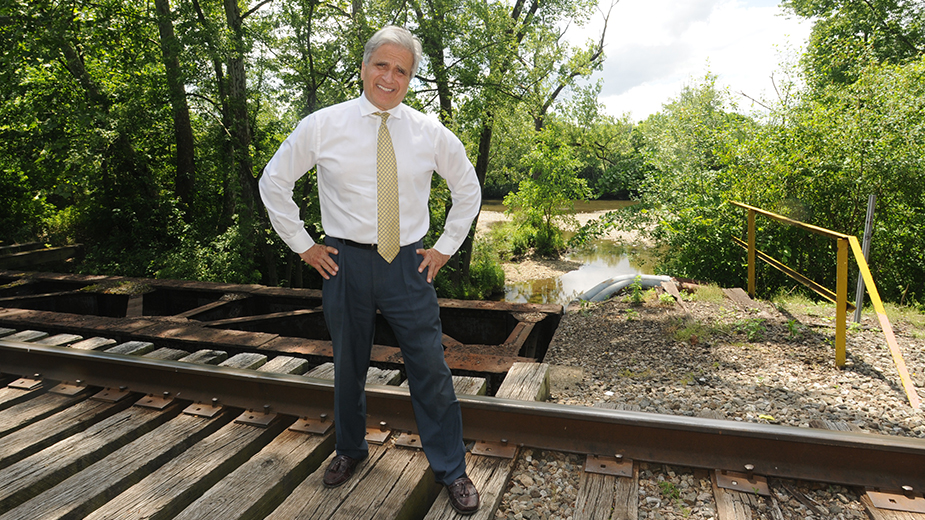

Pictured: Girard Mayor James Melfi stands on tracks at the former Ohio Leather site along the Mahoning River.