YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – Approximately one of every 15 high school students attempts suicide each year and experts say that number is growing.

Between 2012 and 2017, the number of suicide attempts by children increased by 15%, according to a study published by the American Medical Association. It also found that the age of the children attempting and completing suicide is falling to as young as 5.

With the demographic expanding and the number growing, suicide prevention and awareness in school-aged children is critical. Alta Behavioral Healthcare’s Linkages program has been addressing the issue for the last 20 years and is poised to continue its mission of eliminating youth suicide.

The school-based program provides suicide prevention, depression education and suicide screenings to middle and high school students in Mahoning and Trumbull counties. A cluster of suicides at a local school district was the catalyst for the program in the early 2000s, according to Alta CEO Joe Shorokey.

The deaths “devastated the school and community,” he says.

In the aftermath of that tragedy, at the request of the school district and with the support of the Mahoning County Health and Recovery Board, the program was developed. The Trumbull County Mental Health and Recovery Board and ONE Health Ohio now help to fund the program along with the Mahoning County board. The funding makes it possible for the program to be free for the schools.

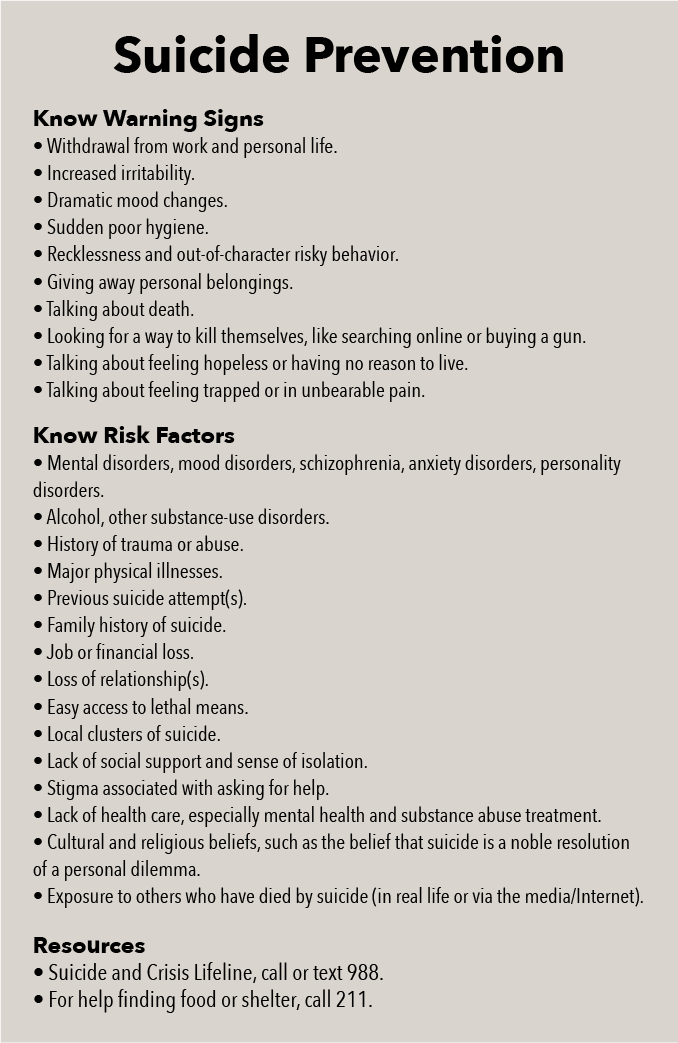

The program operates in two parts: an education portion and a screening portion, says program coordinator Christie Amedia. Using video clips from the national program, “Signs of Suicide,” and a PowerPoint presentation, licensed counselors teach students to recognize the symptoms of depression and warning signs of suicide in both themselves and their peers. Students are taught how to use the Acknowledge, Care and Tell (ACT) model. The model teaches students to respond to signs of depression and signs of suicide by connecting with trusted adults.

The program begins in the fifth grade with a brief introduction to mental health and depression. Amedia says the program has been used with younger children but fifth grade is generally the time children begin to differentiate feelings of normal sadness from more complicated emotions and “big feelings.”

The evidence-based curriculum becomes more involved as the grades progress. Sixth through eleventh graders learn more about the signs of suicide and depression. Eleventh and 12th graders, along with first-year college students, learn about mental health and how it affects their futures.

The program includes a voluntary screening portion as well. Students are given the opportunity to complete a brief screening for adolescent depression. They complete the questionnaire by using paper and pencil and the results are reviewed individually with each student by a Linkages mental health liaison.

The screening allows staff to identify any students who may benefit from speaking with a parent, teacher or guidance counselor. In some cases, students say they believe they may benefit from counseling and the staff member can assist accordingly.

If any students reveal that they are thinking of harming themselves, the students will have immediate follow-ups with a Linkages mental health liaison, and the consenting parent/guardian on the form will be contacted. The interview with the staff member is not a therapy session, but an opportunity to discuss the results of the screening and to decide whether a referral is warranted. The results of the screening will be shared only with school counselors and administrators. To participate in this component, parents must give their consent.

Amedia says she never shies away from those “uncomfortable conversations,” a category that suicide tends to fall into. Those conversations, she says, are the only way change will be made.

“It’s a real problem and we know that our rates of depression and other mental health problems are rising in our teens in this country and this area,” she says. “I embrace the uncomfortable conversations. It might seem difficult at first but it’s always less uncomfortable to have that conversation before someone feels that way, than to have to do it after a tragedy.”

In-school programming is essential, Shorokey says, and being in a classroom setting can make children more receptive. He adds that making the lecture interesting by adding a game and other elements is also beneficial.

As the stigma around mental health decreases, Shorokey says, demand for the program increases. Hundreds more students were screened this past school year compared to the previous.

“I think the stigma is starting to be reduced, while at the same time, the anxiety and depression of students is going up,” he says. “Schools are becoming much more cognizant and sensitive to those issues.”

Shorokey hopes that the program continues to evolve with suicide prevention research. The goal, he says, is to eradicate suicide and to do so, risks must be identified and addressed early.

“The most important thing is to eliminate suicide and to identify early-on risk indicators of suicidal ideation,” Shorokey says. “That’s first and foremost. That’s why we’re doing it.”

Pictured at top: Students are taught how to use the Acknowledge, Care and Tell (ACT) model, says Christie Amedia.