BRACEVILLE TOWNSHIP – During the early summer of 1848, Angelique Le Petit Martin opened a letter addressed to her from a friend living near Marietta, Ohio.

“I am pleased to hear that your prospects are encouraging and shall always be gratified to learn of your welfare and prosperity,” wrote Charlotte Barker on June 26. “Tho’ I must say to you candidly that I have little faith in the well working of ‘the system’ – but let it be tried.”

The “system” to which Barker referred in her letter was the Trumbull Phalanx Corporation, a communal experiment established in 1844 in northwestern Braceville Township in Trumbull County.

That year, Martin and her husband, Giles, relocated from a farm just outside Marietta to the Trumbull settlement. The couple, born in France, immigrated to the United States from England and were acolytes of Charles Fourier, a late 18th and early 19th century utopian and socialist thinker who professed equality between men and women and the formation of harmonious, cooperative societies.

By the mid-1840s, Fourier communities – known as “phalanxes” (derived from the French term “phalanstere,” a communal building) began to appear throughout the United States. It’s estimated that 40 Fourier communities were established across the country, four of which were in Ohio.

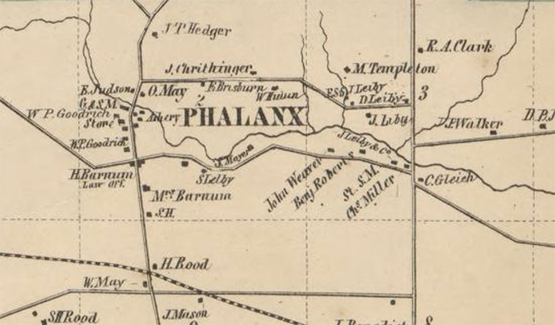

The Trumbull Phalanx, organized by Fourierists based in Pittsburgh, arranged for the purchase of approximately 1,500 acres that hugged Eagle Creek in Braceville, where in 1811 Eli Barnum established a gristmill.

According to a letter from community member Jehu Brainerd dated June 29, 1844, Barnum sold the group “two hundred and eighty acres of the choicest land, about half of which is under good cultivation.” The sale included the gristmill, an oil mill, a sawmill and a “cloth-dressing works” for a total of $3,600. Another 957 acres of “mostly improved farms” were acquired for $16,150 with a cash deposit of $500, the letter stated.

Today, there’s little evidence such a community existed. But its name has persevered. Two small, green road signs with the name “Phalanx Mills” along what is today state Route 534 in Braceville are the only reminders of this experiment in social cooperation. Many of the buildings were torn down. Barnum’s gristmill survived until 1963 when it was destroyed by fire. The community is now dotted with residential homes and just a few may date to the mid-19th century.

Ruth Fulks, a longtime resident of the area now in her 80s, recalls as a child little remained of Trumbull Phalanx.

“All that was left was [the foundation of one of the buildings],” she says. “We used to play on the foundation. Nothing was left.”

Fulks’ family has deep roots in this part of Braceville. Her grandfather Almon Rood ultimately ended up operating the mill along Eagle Creek. An 1856 map of Trumbull County shows two members of the Rood family holding land just south of Eagle Creek.

A PLACE FOR REFORMERS

During the 1840s, the promise and opportunity to create a cooperative society where labor, food, dwellings, education, child rearing and land were shared proved irresistible to reform-minded people such as Angelique Martin. In 1844, she and her family, including three sons, left the Marietta area and joined the Trumbull Phalanx. Their eldest daughter stayed behind to study art in Cincinnati. Lilly Martin Spencer would emerge as one of the most important female artists of the mid-to-late 19th century, advocating for women’s rights through both her work and life.

It was a fertile period for reform and Angelique Martin corresponded and associated with some of the most influential activists of the era in support of women’s rights and abolition. Yet most of the time, she restricted her beliefs to private correspondence instead of publicly agitating for social reform.

Still, she kept in touch with those on the front lines, as evidenced by a collection of her correspondence housed at Marietta College. A letter to Martin from activist Lucretia Mott dated Oct. 10, 1854, reflects on the pioneering women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls held six years earlier. Mott also reminds Martin of the upcoming meeting of the Anti-Slavery Society where “we expect our friend Wm L. Garrison [William Lloyd Garrison, among the most outspoken abolitionists of the period], Lucy Stone and others to be present.”

THE QUEST FOR UTOPIA

Trumbull County proved an inviting place to plant a Fourier settlement since the region already had established a reputation for abolitionist activity and other progressive ideals, says Meghan Reed, executive director of the Trumbull County Historical Society.

“We see a lot of liberal ideas coming out of this area in the 1800s,” she says. “For instance, the Underground Railroad and eventually what would become women’s suffrage. I think we can consider the commune at Phalanx Mills a part of that same mindset that a lot of those early settlers took on.”

Reed says this particular region of the country during this time attracted those who wanted to escape the confines of the East and start from scratch and build new communities.

“It was an area where people went in order to remake their lives,” Reed says. “It took certain grit and gumption to settle land and really grow out into cities and towns. And I think there’s something comparable to what the founders of the Phalanx commune were doing too – they were looking for a space to make a community, a space to make a neighborhood for themselves.”

By the summer of 1844, Trumbull Phalanx had grown to more than 35 families and 200 people. A letter written by Trumbull Phalanx co-founder Nathan C. Meeker in August 1845, expressed nothing short of optimism and prosperity one year into the venture. “A few years will present the beautiful spectacle of prosperous, harmonic, happy Phalanxes, dotting the broad prairies of the West, spreading over its luxurious valleys, and radiating light to the whole land,” he wrote in an editorial in the publication, The Harbinger.

Indeed, the first year of the Trumbull Phalanx appeared to reflect a community on the move. Labor was divided into groups, much of it dedicated to agriculture or working at the community’s mills. “Boys who were idle and unproductive, have become producers, and a very fine garden is the work of their hands,” Meeker wrote in 1844.

Others visiting the commune were also surprised. A passerby – known only as J.D.T., wrote about his impressions in a letter to Pittsburgh’s Spirit of the Age in July 1845. “The members live together, in perfect harmony,” he observed. He also marveled at the industrious nature of the commune, noting its busy flour mill, two saw mills, which cut “six hundred thousand feet per year,” and a shingle and wooden bowl manufacturing operation.

As for the commune’s artisans, “blacksmiths, shoemakers and other branches are doing well.” These revenue streams, the writer said, would be sufficient to retire the community’s debt of $10,189.

PARADISE LOST

There were nevertheless problems that persisted throughout the community, often referred to as the “Association.” Despite the optimism offered by members to the public, it was clear by the late summer of 1845 that the community had begun to fracture.

“Some eight or ten families have lately left,” Meeker wrote to the Pittsburgh Journal on Sept. 13. Some of the families complained about the poor quality of the food. Others left because “they were averse to our carrying out the principles of Association.”

Meanwhile, life was not easy for the residents of the commune, Meeker wrote. Those who elected to join Trumbull Phalanx – there was no vetting process, no religious qualifications, or labor and trade experience necessary – should be prepared for hardship. A member of the commune, for example, should be willing to “endure privations, to eat coarse food, sometimes with no meat, but with milk for a substitute, to live on friendly terms with an old hat or coat,” he related, and maintain long work days. Those who “sigh for the flesh-pots and leeks and onions of civilization [or] growl because they

can not have eggs and honey and ham and warm biscuit or butter for breakfast,” he wrote, should stay where they are.

Financial problems and debt remained a constant issue with Trumbull Phalanx, while Meeker in August 1847 lamented the lack of “scientific and industrial men, with some capital.”

Moreover, the propensity of Eagle Creek to flood (today, the creek remains notorious for overflowing during heavy rains) helped to spread fever and “ague” throughout the community. These illnesses, while not lethal, incapacitated the labor force for extended periods of time. By December 1847, Trumbull Phalanx had dissolved.

“We have fallen,” wrote G.M.M. [possibly Giles Martin] on Dec. 3, 1847, to The Harbinger. “We will try and try again.”

Others were more forthcoming. An account written by someone identified only as “J.M.” described a settlement beset with swampy land that could not be cultivated, floodwaters that spread “a great deal of sickness” that lasted months, and a freewheeling admissions policy that attracted those “with the idea that they could live in idleness at the expense of the purchasers of the estate.”

The community was also plagued with religious quarrels, survived on barter rather than cash, and at least for the first year experienced insufficient housing – many of the residents were “huddled together like brutes,” he wrote. If that weren’t enough, there were suspicions of corporate embezzlement.

“There was another keen fellow, a preacher and a lawyer” who served as a secretary and treasurer for the commune, J.M. wrote. “When there was any money, he had the management of it; and I believe he knew perfectly well how to use it for his own advantage.” In short, J.M. concluded that Trumbull Phalanx “was the most unsatisfactory experiment attempted in the West.”

The community made an effort to rebuild in 1848. This also failed.

Angelique Martin, nevertheless, continued to live in Trumbull Phalanx until her death in 1865, never wavering on her dedication to social reform. A letter to Mr. Garrett Smith, dated Jan. 22, 1852, concludes, “Your sister in human progress. Angelique Le Petit Martin.”

Pictured at top: Road sign marks the site of Trumbull Phalanx, a 19th century cooperative society.