YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – Approximately 14 years ago, Richard Marsteller stumbled upon a headstone that stirred his curiosity.

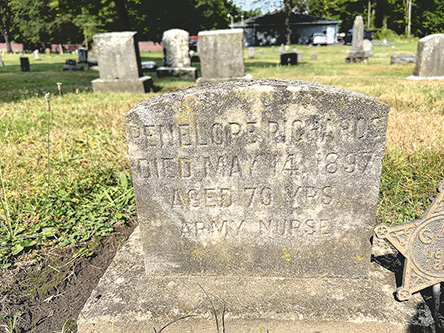

As he walked the aisles of grave markers at Oak Hill Cemetery in Youngstown, he noticed one of a woman by the name of Penelope Richards. Her birthdate is unknown, and the day of her death is engraved as May 14, 1897, approximately age 70.

But as Marsteller, the cemetery’s superintendent, examined the stone more closely, he became intrigued about the partially faded inscription at its base: “Army Nurse.”

Marsteller thought Richards’ approximate age at her death placed her service at or near the period of the U.S. Civil War; but he wanted to be sure. “I’ve looked at a lot of headstones here, but I’ve never seen one that said ‘Army Nurse,’” he says.

What Marsteller didn’t know – and couldn’t know from the headstone – was that Richards was Black.

He brought the matter to the attention of Steffon Jones, who has led a research team for nearly 30 years at Oak Hill to help identify and honor the burial sites of veterans, especially African Americans who served in the military.

“I had seen the headstone before,” Jones recalls. “But I didn’t know she was an Army nurse.” All he really knew about Richards was that she was the wife of Henry Richards, an African American Civil War veteran who is also buried at Oak Hill.

Through extensive research that took several years, Jones was able to confirm that Penelope – often referred to as “Penny” – enlisted as a contract nurse in February 1863, at what was then referred to as Contraband Camp and Hospital in Washington, D.C.

The camp and hospital were constructed in 1862 specifically for tending to former enslaved people who fled north as the Union armies occupied pockets of the Confederacy. As such, they were considered contraband of war. As African Americans were recruited to fight for the Union, the hospital and camp were also used to care for wounded Black soldiers.

In the ensuing years, that camp relocated to the grounds of what is today Howard University under the new name, Freedmen’s Hospital. It was the first hospital in the United States established to provide medical aid to former enslaved people and exists today as part of Howard University Hospital.

Discovering a nurse who served in the U.S. Civil War interred at Oak Hill is rare enough, Marsteller says. However, to his knowledge, identifying a Black nurse employed in the Union army who is buried in Youngstown is unprecedented. “This is the first one that I know of,” he says.

Reconstructing a Life

Jones pieced together Richards’ life through military pension records he was able to obtain through the National Archives.

Additional census records, newspaper items and other primary sources added critical information about her later days in Youngstown.

According to the census of 1870, Richards was born Penelope Wilson in approximately 1835 in North Carolina.

Although likely, Jones has no record of whether she was born enslaved. In 1870, census data show that she and her husband lived in Youngstown’s 5th Ward, lists her occupation as “keeping house” and affirms that she could not read or write.

Her husband, Henry, was born enslaved in Tennessee in 1819 and enlisted in the Union Army on July 16, 1863, according to pension records. He served for three years as a cook in Company G of the 125th Ohio Volunteer Infantry.

Life at Contraband Camp was not easy.

Jill Newmark, exhibition specialist in the History of Medicine Division of the National Library of Medicine, in her article “Contraband Hospital 1862-1863: Health Care for the First Freed People,” writes that more than 40,000 enslaved people fled to Washington in the wake of the D.C. Emancipation Act of 1862, which freed all enslaved people in the nation’s capital.

This presented a challenge for the federal government, as it wrestled with how to provide food, shelter and medical care for these newly emancipated freedmen.

Contraband Camp and Hospitals “were constructed as one-story frame buildings and tented structures” that would provide temporary housing and hospital care for African Americans. The camp provided separate quarters for men and women, as well as a tented area reserved specifically for smallpox patients. By the end of 1863, “they had processed over 15,000 individuals and had 685 residents.”

According to Newmark, “Conditions at the camp were poor and unhealthy. The damp and swampy ground on which the camp was built along with a lack of an adequate supply of fresh water and the limited distribution of meager supplies contributed to the camp’s conditions.”

These factors helped breed health problems such as diarrhea and respiratory infections.

It was under these working conditions that Richards found herself in February 1863 when she enlisted as a nurse.

As Newmark writes, “Nurses at Contraband Camp hospital were primarily made up of residents of the camp” as “newly arrived fugitive slaves were an ideal source of labor for the hospital, and the hospital was an excellent first employer for camp residents.”

Although highly probable, it’s unclear whether Richards was among those who crossed into Union lines from slavery and fled into the camp before enlisting.

What is clear is that government records confirm her service there.

According to the U.S. War Department’s Records and Pension Division, “Medical records show that she served as a nurse in Contraband Camp (Freedmen’s Hosp.) Washington, D.C., under a contract made Feb. 1, 1863, and annulled Dec. 19, 1863; and again in same hospital under a contract made Aug. 21, 1865, and annulled at her own request April 12, 1866. Nothing additional found.”

Other pension records attest to Richards’ service at the hospital. In an affidavit in support of her pension claim dated Dec. 15, 1892, Robert Mackey of Youngstown said he “became personally acquainted with the applicant during the war of 1861-1865 at Washington, D.C.”

Mackey attests to spending five months at Freedmen’s Hospital in 1865 “on account of an injury and saw the applicant there in the capacity of a nurse and have been well acquainted with her.”

Later Years

Following the war, Richards and her future husband, Henry, relocated to Youngstown. They were married here in 1869. Where or how the two met is unknown, but records show the couple made their home at 533 Plum St., just blocks from Oak Hill Cemetery. The house no longer exists.

By 1892, both were facing serious health problems, Jones says. Richards was showing signs of dementia, while her husband suffered from severe respiratory issues. Richards would eventually live under the guardianship of Parish Hall, a neighbor who is also buried at Oak Hill. Her pension case was handled by W.R. Stewart, the first practicing Black attorney in Youngstown, Jones says. Eventually, she was successful in securing a pension of $12 per month.

According to a death notice in the Youngstown Telegram, Henry died Jan. 17, 1897, from pneumonia. Richards died from dementia May 14 of that same year.

“It’s incredible that we have a Black husband and wife buried at Oak Hill who both served during the Civil War,” Jones says.

Jones says his team – the Oak Hill Volunteer Research Team – has spent endless hours researching the cemetery and it’s vital that stories such as Richards’ are told and preserved.

“This is really important that you have a Black Civil War nurse buried here who served our country,” he says.

Marsteller agrees. “If you want to know about history, you’ve got to go out and find it,” he says. Oak Hill, he adds, is rich with local history.

Interred there are men and women from the city’s most prominent families, such as Tod, Pollock, Stambaugh and Butler, and much is written about them.

Then there are those such as Richards, who, without Jones and his research team, would never have their stories told. “These are the people I’d like to know,” Marsteller says.

Pictured at top: Richard Marsteller, left, superintendent at Oak Hill Cemetery, and researcher Steffon Jones kneel at the headstone of Penelope Richards.