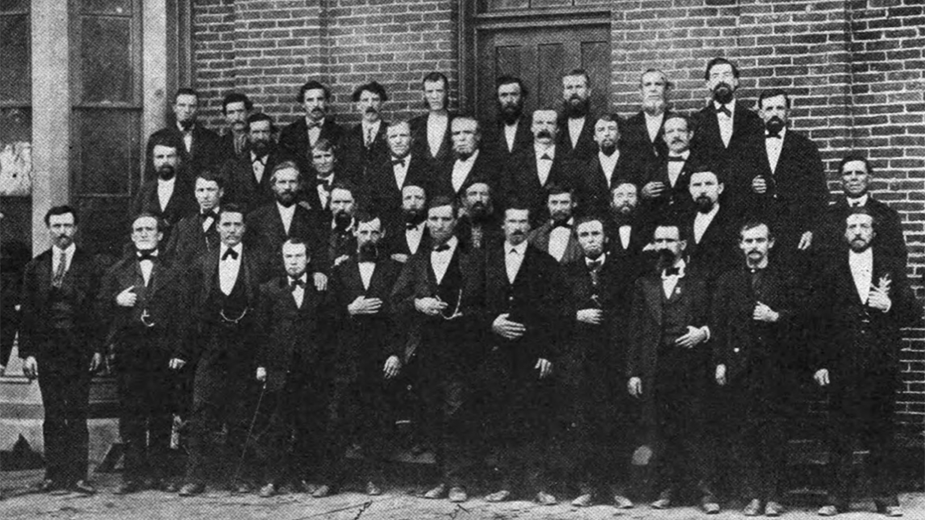

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – On Oct. 13, 1873, some 35 labor leaders from across the Midwest met at the Iron Boilers Hall in Youngstown to address the working conditions of coal miners across the country.

By the end of that day, a new national union had been born.

The event underscores just how relevant the Mahoning Valley was and is to organized labor. It set the stage for more than 150 years of petitioning for the rights of workers.

From trade unions following the Civil War, to representation in the region’s teeming steel industry, then leading the country in organizing professional occupations such as nurses and teachers, the rank-and-file struggle continues.

Labor organization found its way to the Youngstown Duty Nurses Association, which in 1966 initiated the first nurses’ strike in Ohio. Teachers as well formed bargaining units to assert their rights.

Today, with organized labor ranks declining across the nation, unions face different challenges. New directions in the Mahoning Valley’s economy – the development of electric-vehicle battery cells for the automotive industry, for example – leaves unions with no guarantee of representation in their industry, while workers in the public sector are feeling pressure to make concessions.

WHEN COAL WAS KING

In 1873, the Miners National Association was an early effort among miners to collectively challenge unfair wages, poor working conditions and the lack of government regulations or worker protections.

It was likely the first time that organized labor launched such an ambitious initiative in Youngstown on a national scale. More important, the platform the Miners Association established laid the groundwork for more than 150 years of labor organizing in the Mahoning Valley.

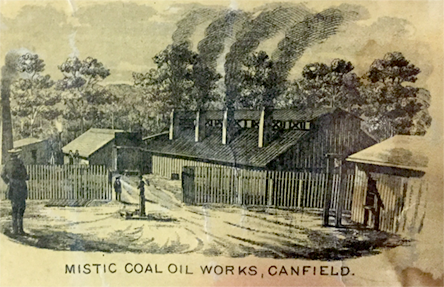

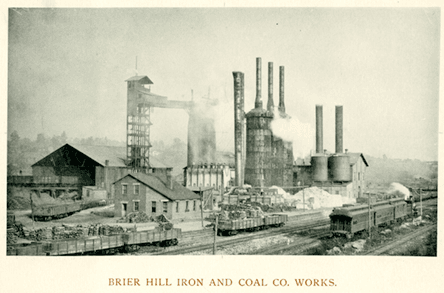

Youngstown proved a sensible location to organize the Miners Association union. Coal mined in the region was among the best in the country. “Brier Hill” block coal, also known as “Sharon block” coal, came with ingredients so pure that it didn’t require additional processing into coke, which was used to fuel the major iron works that had sprung up 10 years earlier during the Civil War. From Youngstown, this coal was shipped by canal and rail to Cleveland, Chicago, Pittsburgh and other growing industrial hubs.

Trumbull County was especially rich. In 1873, the county accounted for one-fifth of the entire state’s coal production, according to Ben Lariccia, co-author of “Coal War in the Mahoning Valley: The Origin of Greater Youngstown’s Italians.”

“It provided the foundation for Youngstown’s future wealth,” Lariccia writes. “Youngstown was very much the center of organizing because of this coal.”

Lariccia, a native of Youngstown who lives in Philadelphia and writes extensively on Italian-American history, says the coal mines on the outskirts of Youngstown – especially in Liberty and Hubbard townships – drew an extensive immigrant population from Wales. “They were the main ethnic group in mining in this area and were successful in organizing,” he says. “They had a lot of experience in Wales.”

A bitter strike that began Jan. 1, 1873, across the Mahoning and Tuscarawas valleys in Ohio, and the Shenango Valley in western Pennsylvania, had far-reaching significance for labor, the area’s immigrant population, and the fate of the region’s coal mining industry. Miners employed at the Church Hill Coal Co. in Liberty Township, followed by workers at the Mahoning Coal Co. in Hubbard Township, were the first to walk out, protesting a decision by Ohio’s mine owners to reduce wages by 20%. Within a month, more than 7,500 miners across the region were on strike.

Mine owners and investors, however, were prepared, sensing a strike was likely once wage cuts took effect, Lariccia says. Youngstown industrialist Chauncey Andrews, who founded Andrews & Hitchcock in 1858, had in 10 years emerged as the single largest coal producer in Ohio. In December of 1872, he chaired a coalition of Ohio mine owners during a meeting at the Tod House in Youngstown where they not only agreed to slash wages, but to also recruit Black workers from Virginia as strikebreakers.

“Even before 1873, the coal mine operators met and decided they would bring in strikebreakers,” Lariccia says. When the effort to bring in Black strikebreakers backfired, mine owners hired Italian immigrants from New York City as replacement workers. “The Welsh miners took great offense to it and this is one of the early instances of when immigrants are used as strikebreakers,” he says. The tactic worked and the local miners all but ended their strike in May 1873. Some of the Scottish and Welsh miners were singled out and denied their old jobs.

Tensions then erupted between the miners and the immigrant camps, Lariccia says. For several weeks, miners pelted with stones the boarding houses that lodged the Italian immigrants and left behind threatening messages. After an altercation with one of the strikebreakers, Giovanni Chisea, a mob of mostly Scottish and Welsh miners surrounded a boarding house the Church Hill Coal Co. owned.

The crowd set fire to the building, forcing the occupants out. As strikebreakers fled the burning building, they were attacked. Chisea was singled out and beaten to death, Lariccia says.

“It was a lynching,” he says. “Probably the earliest lynching of an Italian in the United States.”

Immigrant strikebreakers were used on at least 30 other occasions, Lariccia says, after the 1873 strike. Moreover, the strike damaged overall output of the coal industry in the region, allowing manufacturing centers such as Cleveland and Pittsburgh to overtake the Youngstown area in coal production.

DRIVE TO ORGANIZE

The futility of the coal miners’ strike in the Mahoning Valley beckoned efforts to reorganize on a large scale, resulting in the formation of the Miners National Association in Youngstown. From the outset, it was clear that the organization had both labor and political reform on its mind. Among its stated purposes was to urge “upon all miners the necessity of becoming citizens and to use the ballot to bring what influence they could to obtain legislative enactments.”

Other calls for reform included shorter workdays, worker compensation benefits, the right of a worker to sue in the case of employer negligence, and to “provide a fund for the payment of weekly allowances to men on strike.”

At the same time, the union understood some of the lessons of the previous months, as its constitution encouraged “to eliminate as far as possible the causes of strikes and to accept the principle of arbitration wherever practicable.”

By 1875, the Miners National Association comprised 347 locals and had a combined peak membership of 35,354. The timing, however, couldn’t have been worse. By the close of 1873, the country was in the grips of an economic depression and wouldn’t recover for another four years. As the economy collapsed, so did the Miners Association.

OTHER UNIONS ORGANIZE LOCALLY

The post-Civil War era brought enormous prosperity to Youngstown and the Mahoning Valley. As the iron industry made the transition to steel production, the area experienced a significant building boom, making the construction and building trades fertile ground for union organization, says Bill Lawson, executive director of the Mahoning Valley Historical Society.

“One of the pretty early unions was the Bricklayers and Masons Union No. 8,” established in Youngstown during the latter half of the 19th century, he says. “In the 20 years or more after the Civil War, we begin to see the first organized groups.”

The Bricklayers and Masons union, Lawson continues, was especially significant, since one of its founders was P. Ross Berry, a celebrated African-American stonemason and self-trained architect who built dozens of the city’s landmarks. “It was an integrated union,” Lawson says. Oscar Boggess, a Civil War veteran who was born a slave in Virginia during the 1830s, was an early member. “They were a tight-knit group of integrated, skilled tradesmen.”

By the late 19th century, Youngstown was home to labor organizations that represented industrial workers, trades and assorted crafts and skills. A city directory from the 1880s lists groups such as the Clerks Union, No. 50277; the Youngstown Typographical Union, No. 200; the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, No. 329; the Brotherhood of Railroad Brakemen, No. 21; and the Cigarmakers Union, No. 152.

FIGHT FOR RECOGNITION

Still, organized labor had little leverage during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly in the Mahoning Valley. Strife between workers and management often commanded headlines across the country – Haymarket Square in Chicago in 1886, the Homestead Strike of 1892, the Pullman Strike of 1894 – with such events invariably ending as a loss for labor with state and federal governments throwing their support behind industry.

Although skilled workers made advances during this period, unskilled labor did not. In late 1915, workers at Youngstown’s Republic Iron and Steel Works began to walk off the job when the steel industry ignored the rank-and-file’s request for a raise to 25 cents an hour. The strike spread to Youngstown Sheet & Tube’s operations in East Youngstown – today Campbell.

Underlying social conditions and low wages served as kindling for an explosive situation. On Jan. 7, 1916, 1,000 strikers were met with armed company guards outside Sheet & Tube’s north entrance. Shots rang out and the crowd dispersed. But then the strikers turned angry. That evening, East Youngstown erupted in a riot that left three dead, dozens wounded, 34 buildings destroyed and more than $1.5 million worth of damage. Ohio Gov. Frank Willis called in 24 companies of the Ohio National Guard to restore order.

What the crowd didn’t realize was that officers of Republic and Sheet & Tube had earlier agreed to boost workers’ wages to 22 cents an hour.

“It was a struggle,” Lawson says of the workers. “There was a feeling of being underpaid, underappreciated, while company owners tried to gain critical mass.”

As unions gained traction with the railroads, construction and local delivery services, major industries such as steel and auto remained unorganized by the early 1930s.

The Great Depression changed that, says John Russo, visiting scholar at the Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor at Georgetown University. “It had an enormous impact in the Valley,” he says.

In 1935, Congress passed the Wagner Act, which guaranteed the right of employees to form a union and to bargain collectively. The law also created the National Labor Relations Board, which had the authority to prohibit unfair labor practices.

Emboldened by the law, unions sought to organize unskilled workers under the Congress of Industrial Organizations, or CIO. By 1937, the union of unions boasted 3.7 million members.

That year, General Motors was forced to recognize the United Auto Workers after a 44-day sit-down strike in Flint, Mich. U.S. Steel Corp. soon followed and recognized the steelworkers’ union.

“Little Steel” companies such as Republic and Sheet & Tube resisted, however, setting the stage for another violent showdown in the Mahoning Valley. The Little Steel Strike began in May 1937 when members of the Steel Workers Organizing Committee voted to strike Republic, Sheet & Tube and Inland Steel. During the strike, Republic’s Mahoning Valley mills in Youngstown and Warren remained operating, infuriating picketers.

On June 19, 1937, violence erupted outside of Republic’s Poland Avenue plant in Youngstown. Officers fired tear gas canisters into a crowd of protesters and the situation escalated into a gun battle that left two strikers dead. When the strike ended that summer, Little Steel had won and still refused to recognize the SWOC.

In 1941, the National Labor Relations Board mandated that Little Steel recognize the union.

“Then, during World War II, these companies and the country really needed the support of labor unions,” Russo says, “and unions continued to grow.”

Yet no sooner did the war end in 1945 than major figures in Congress – most importantly Republican Sen. Robert Taft of Ohio – lead the charge to restrain organized labor, Russo says. In 1947, Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act with the support of Democrats. That measure prohibited wildcat strikes, jurisdictional strikes, closed union shops and monetary donations from unions to federal political campaigns.

“There was a type of social compact in the 1950s and 1960s that the full impact of Taft-Hartley would not be fully implemented,” Russo says. “But during the 1970s – that’s when the attacks really happen.”

This chapter in local labor history corresponds with two major movements during the 1970s – deindustrialization and globalization, Russo says.

“The last 50 years have been very dramatic because of deindustrialization,” he says. “It’s hurt the manufacturing sector that provided the middle class jobs this Valley was built on.”

When the major union jobs were lost during retrenchment of the steel industry in the Mahoning Valley, it ripped the middle class apart. “A lot of union jobs were lost. People moved out of the area to other parts of the country,” Russo says.

This exodus accelerated when companies such as Delphi Packard began to shift production from Warren to Mexico in the late 1970s, then to China and elsewhere in Asia during the 1980s and 1990s.

Russo, formerly the director of Working Class Studies at Youngstown State University, says while public sector unions remained strong, there are ongoing political efforts to undermine their influence. This was evidenced a decade ago when Gov. John Kasich advocated passage of Senate Bill 5, which would have all but squashed public employee unions in Ohio.

While the measure was voted down as part of a ballot referendum, Russo says attacks on public unions continue. “I think there’s palpable anger among teachers, government employees and police and fire,” he says.

Russo does acknowledge opportunities exist for organized labor as the Mahoning Valley economy diversifies.

“I still think unions – the UAW – has leverage in the auto industry,” he says, referring to Ultium Cells LLC’s – a joint venture between General Motors and LG Energy Solution – new $2.3 billion battery cell manufacturing plant in Lordstown. “I think they’ll be in a position to broker some type of deal without a fight.”

Still, he observes, the demise of labor’s influence and the lower standards of living across the Mahoning Valley are linked. “What makes this Valley different is that the labor unions fought deindustrialization, fought the disinvestment,” he says, “and we’re living with the results of the decline of labor unions in the Mahoning Valley.”

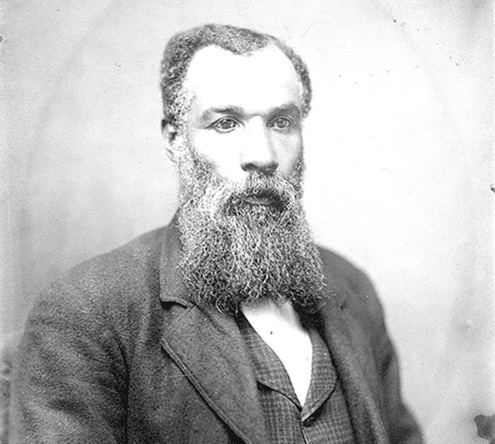

Pictured at top: The Miners National Association tried to form a national union in 1873. Source: United Mine Workers Journal.