Blazing a Wine Trail in the Grand River Valley

Editor’s Note: This week The Business Journal focused on Ohio’s growing wine industry. Be sure to watch the videos. See links below.

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – There are times when a reporter must take on an assignment that tests his mettle. In late May, it was clear that this reporter, along with the producer of the Daily BUZZ, Michael Moliterno, had such an assignment.

Spend two days touring Ohio wineries and, in the words of our publisher, “Have fun – and stay out of jail.” Some guys have all the luck.

So, we packed our bags and headed north. The road took us to the Grand River Valley viticultural area, which includes portions of Lake, Geauga and Ashtabula counties. There are 30 wineries there, with more opening each year. Which means we barely scratched the surface.

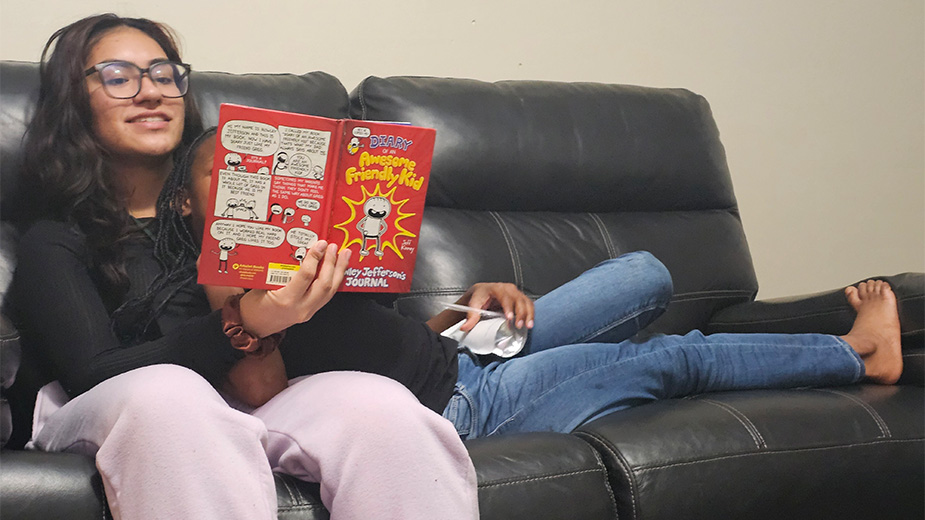

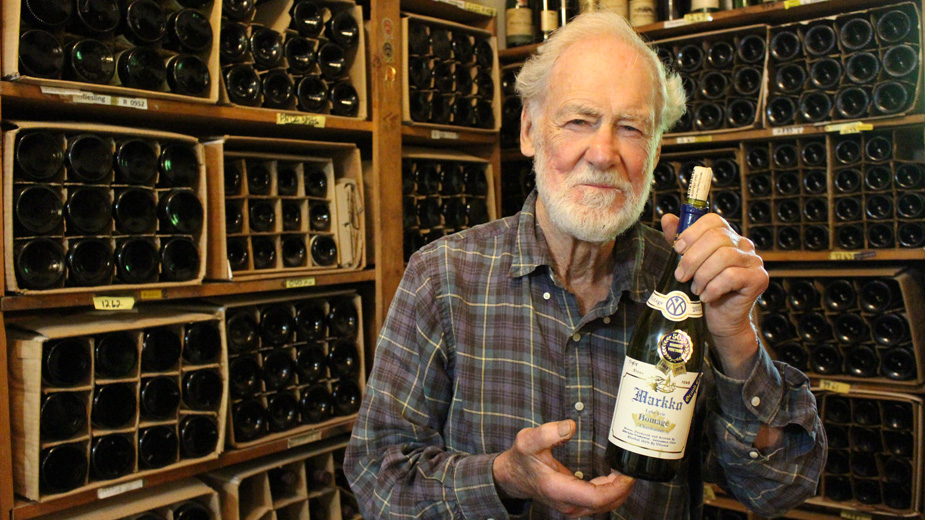

Markko Vineyard

In the cellar of Markko Vineyard, Arnulf “Arnie” Esterer uses a wine thief to draw a sample from one of the many oak barrels, then drains the wine from the glass tube into a tastevin. Light reflects off the shallow, metal tasting dish through the wine, allowing Esterer to observe its clarity.

He gently swirls the wine, smells it, sips it and swishes it in his mouth before spitting it onto the ground.

“If you have to taste 100 barrels, you got to stay sober,” he says with a laugh. “It’s a tough job.”

A tough job that Esterer has been doing since 1968 when he founded Markko with the late Tim Hubbard at 4500 South Ridge Road West in Conneaut. The winery sits into the woods off a gravel road near Interstate 90. Parking is minimal and visitors are often greeted by Esterer’s two English sheep dogs.

For those familiar with some of the larger wineries around Geneva, Markko Vineyard provides a quiet reprieve. The tasting room is about the size of a typical dining room and sliding glass doors lead out to a small porch where guests can sit with a glass of wine. When Esterer isn’t working in the cellar or tending to the 15-acre vineyard, he can be found here meeting with customers.

Esterer is something of an elder statesman among the wineries in the Grand River Valley. Ask any of the winemakers in the area about Esterer and they’ll either know of him or have a story about how his advice helped save one of their harvests.

In the beginning, Markko was a cooperator of Dr. Konstantin Frank, the Ukranian winemaker whose experience and research in growing European vinifera grape varieties in cold climates helped lead the way for growing such varieties in the northeastern United States. As a cooperator, Markko bought Frank’s vines and started planting them in Ohio in 1969. Concord and Niagara grapes are the varieties native to the area, but this relationship allowed the winery to grow chardonnay, pinot noir, riesling, cabernet sauvignon and pinot gris.

“If we can make a wine with those grapes and we get to show how they do here [with] our soil, our climate, then we have a chance to enter the world market,” Esterer says. “We want to make a distinctive wine that reflects what this region is.”

Pictured: Arnie Esterer has made wine at Markko Vineyard in Conneaut for 50 years.

Wine characteristics are derived from the soil, which he says is ideal for cultivating vineyards. The proximity to Lake Erie helps to moderate the climate by keeping it cool during the hot summer months. During the fall, the water remains warm, which heats the land, allowing for a longer growing season.

“Grapes don’t like big changes,” he says. “If we go from 50 degrees above zero to 10 degrees, or zero, it will do a lot of damage. The lake smooths that out.”

While changes to the climate are slow and subtle, he says, warmer weather will increase rain and make it harder for growing grapes. Each year, he tries new ways to trellis, or arrange the vines to suit the climate.

Esterer doesn’t add any preservatives or sugar, so his wine tends to be dry. The winery produces about 1,500 cases of wine annually, but has the capacity to produce 2,000, or 25,000 bottles. With 15 acres of vineyard, “we could produce a lot more,” he says, or sell some of the grapes to other wineries.

Over the years, foot traffic has increased and Esterer sees visitors from all over Ohio as well as Pennsylvania, Indiana and Michigan. The vineyard straddles I-90, which is a big help, he says.

“That’s a major transcontinental highway,” he says. “People going anywhere from New York to Chicago or Boston. They tend to come through here. And when they hit wine country, they know it.”

Before we leave Markko, we make sure to buy a few bottles of chardonnay, which Esterer says has the potential to be a defining wine in the region. It ripens two weeks earlier than riesling, which also grows well here, and fits the climate better, he says.

“Chardonnay is the largest-selling white wine in the world,” he says. “We think we can make them better here than California.”

Laurello Vineyards

After checking in to the hotel and grabbing some lunch, our next stop was Laurello Vineyards at 4573 state Route 307 in Geneva. The winery sits on a little more than eight acres where the company grows Concord, Catawba, chardonnay and riesling grapes as well as some high-end reds.

In 1991, Larry Laurello Jr. and his wife, Kim, bought the property, which was the former Burkholder fruit farm. Wine-making was a hobby for Laurello, who did it in his basement for many years, says the general manager, Danielle DiDonato.

“That was getting to be a problem for his wife, because it was growing out of the basement. And she was kind of getting fed up with it,” DiDonato says with a laugh. “He wanted to make his dream and hobby become a reality.”

After years of getting everything up to the standards of winemaking, Laurello Vineyards opened in 2002. The Laurellos maintained the farm buildings and used them to house their equipment, tanks and barrels.

The winery produces 4,000 cases of wine annually and bottles wine three to four times monthly, DiDonato says.

“Our cellar team is in there daily just doing different casks and checking wine levels, cleaning and racking barrels,” she says.

Along with Laurello’s vineyard, it partners with other growers to source some of its grapes, she says, including Debonné Vineyards in Madison and some Conneaut Creek wineries. Most, if not all of the growers in the area, have a “tight-knit relationship” and don’t consider each other competition, she says.

“We don’t look at it that way,” she says. “We help care for the vines and then we get our portion of the harvest come late fall.”

Pictured: Laurello ages high-end reds in French and American oak barrels, says Danielle DiDonato.

The company’s full-time solicitor/sales director helps to maintain Laurello’s retail presence in Ashtabula and Lake counties as well as the Cleveland area. Laurello wine is available in some high-end restaurants in Cleveland “and we’re getting into some of the stores out that way as well,” she says. “So it’s growing every year.”

Customers can sample wine flights or enjoy full bottles inside the main building or on the outdoor patio that seats about 250 people, which is usually full during the summer concert series of the winery. Two private rooms are available for parties of 30 or 50 guests.

DiDonato, involved in the regional wine industry since she was 13 years old, says there’s been an upswing in Laurello’s business over the last few years. Facebook and Instagram lets the company inform customers of specials and events, including its weekly Meal for the Cure – a charity dinner that benefits breast cancer research.

“I think that is a great way to give back and our customers really appreciate it as well,” she says.

Laurello also promotes the quality of its red wines, which DiDonato says are better today than they were when she first started working in the industry. Reds are difficult to grow in Ohio, but new techniques have kept the grapes safe from Ohio winters, she says.

Two reds of note – Laurello’s 2012 cabernet sauvignon came from “one of the best growing years around here that we’ve had in a long time” – produced great flavor. The cabernet sauvignon was aged 30 months in French oak barrels. The recently released 2016 cabernet Franc boasts a “delicious fruit character with a little black pepper,” she says.

“It’s something that people have to get their lips and their tongue on,” she says, “because you’re tasting Ohio soil. You really can’t compare it to a California wine; it’s not even fair to do. It’s such different styles of an art.”

Reds are kept in French and American oak barrels, each costing between $1,000 and $1,500. Barrels are typically replaced to the tune of 10 to 20 each year, depending on how many are decommissioned.

Laurello took a new approach the last few years with its Cosmo wine, named after Laurello’s grandfather. The company ages a red blend in used Jack Daniels barrels that it buys from the Tennessee-based producer of American whiskey.

“The finish on the wine has a bourbon taste,” DiDonato says. “It’s awesome.”

Grand River Cellars

We started Day No. 2 bright and early – after an appropriate amount of water and coffee, of course.

Tucked away on a wooded piece of farmland in Madison, Ohio, sits Grand River Cellars. Only four of its 53 acres are planted with grapes. The rest is either wooded or developed farmland that is used to grow soybeans, corn and anything else the winery needs for its full-service restaurant.

Cindy Lindberg owns Grand River Cellars with her business partners, Tony and Beth Debevc, who also own Debonné Vineyards.

While most of the grapes and juices Grand River uses to make its 20 wine varieties come from Debonné, it grows its vidal blanc on site, which it uses for its iced wine. Grand River produces more than 10,000 gallons of wine annually. The vidal blanc grapes are hand-picked and pressed frozen. Grapes must be frozen in temperatures below 17 degrees to properly freeze the natural water content of the grape. 2005 Vidal Blanc Ice Wine of Grand River earned the Ohio Director of Agriculture’s award for the best dessert wine in the state.

“Not only do we produce it, but all of our ice wines are internationally award-winning wines,” Lindberg says. “We just have the perfect temperatures, whether that’s a positive thing or a negative thing to some people.”

Each year in March, Grand River works with Debonne, Ferrante Winery, Laurello Vineyards and St. Joseph Vineyards to hold the Ice Wine Festival. The region takes ice wine very seriously, she says, because it is one of the few areas in the world that can produce it, the others being Germany, Austria, Canada, Oregon and Michigan.

The Grand River Valley Ice Wine Festival runs the first three Saturdays in March and began as a way to make the area a year-round destination. Last year, the festival drew more than 3,400 visitors, creating “a nice boost to the economy,” she says.

“Now we’re filling the hotels, the restaurants are busy [and] the gas stations are all busy,” she says.

Pictured: Cindy Lindberg owns Grand River Cellars, a sister winery to Debonné Vineyards.

Its dry rosé, a relatively new wine, has increased in popularity since being introduced about five years ago, Lindberg says.

It parallels a trend in the wine industry that shows the rosé wine category outpacing overall U.S. wine growth, reports Nielson, while still representing only 1.5% of the total table wine category.

The “pink drink” at Grand River is made from cabernet Franc, because “it’s a good, hearty grape that grows well in this region,” Lindberg says.

“I really have always enjoyed that tartness of the dry rosé,” she says. “And it’s a great summer wine.”

Additionally, the Grand River Valley is part of the great pinot belt, “which is an area of land that actually spans the entire globe,” she says. “And that’s where it’s said to be that the best pinots in the world are grown” because of soil and climate.

“It’s a cool-climate varietal, and we’re a cool climate,” she says.

This month Grand River Cellars is working with 13 other wineries to host the Pinot Quest, during which customers can travel from winery to winery and sample the pinot varietals in the area, including pinot grigio, pinot noir and pinot chardonnay. The goal is to get people more familiar with pinots and to establish the area as a destination for those varietals.

The winery hosts special events of its own, including private events in its dining room as well as its wine cellar downstairs. Charity events are booked on Monday and Tuesday nights and are usually spaghetti dinners for local sports teams or wine tastings for other organizations. Hosting such events and maintaining a connection to the community is as important to the business as it is to the charities they benefit, she says.

“We want people to realize that we’re out here,” she says. “But we still care about the community and want to make sure that we’re helping the community as we grow. And I think that’s the key to doing these events.”

Ferrante Winery

Our final stop was to one of the most popular estate wineries in the Grand River Valley, Ferrante Winery & Ristorante in Geneva. The family-owned winery is operated by the third generation of the Ferrante family. It began in 1937 with Nicholas and Anna Ferrante.

They lived in the Collinwood area on the eastern side of Cleveland and operated a winery there. Grapes were raised and harvested at the vineyard, then trucked to the Collinwood winery. Their sons, Peter and Anthony, took over the business and operated the Collinwood winery until the mid-1970s. Peter, a carpenter by trade, oversaw construction of the winery at 5585 state Route 307, which opened its doors in 1979.

In the beginning, everything was done by hand, says Carmel Ferrante, operations manager and Peter’s daughter. The winery produced 5,000 gallons annually. When Carmel’s brother, Nick, came on to help their father, the business started to grow. At the time there were 54 wineries in Ohio.

“Today, I believe there are 276 wineries in the state of Ohio,” Ferrante says. “In the last 10 years, we’ve seen a lot of urban-type wineries, a lot of wineries come in focus.”

She attributes the rise of the industry to increased popularity of wine among all generations, but also family traditions. Ferrante recalls wine being an important part of her family’s gatherings. Her parents drank a glass every night with dinner, she says.

The nearly 40-acre vineyard is in full view of the restaurant and the courtyard. Ferrante primarily grows vinifera grapes, including cabernet Franc, riesling, chardonnay, pinot gris and vidal blanc. Like other wineries in the region, rieslings and other white wines grow very well at Ferrante. The 2017 winter wasn’t as severe and the long hot summer produced a great harvest, she says.

“Our 2017 vintages, like our pinot grigio coming out, our dolcetto, they’re off the charts,” she says. “They’ve already won awards and they’re not even for sale yet.”

Customers can still buy a bottle of award-winners in previous years. Ferrante’s 2016 vintages did very well this year at the San Francisco Chronicle Wine Competition, including its Double Gold Medal-winning 2016 riesling, the Best of Class 2016 gewürztraminer and the Double Gold Medal-winning 2016 ice wine.

Pictured: Alyssa Ollis and Carmel Ferrante toast sunny weather in Ferrante Winery’s courtyard.

Although the average Ohio wine drinker still prefers a sweeter wine, off-dry wines such as the gewürztraminer and the grüner veltliner are becoming more popular, Ferrante says. She says customers are becoming more educated on the wines and exploring the different varieties. Ferrante looks to expand her customers’ palates even further by educating them on how the grapes are grown and how to read the labels.

“So they understand what they’re drinking and they can actually have fun with it and share it with their family and friends and make it a tradition in their lives,” she says.

As the Grand River Valley attracts more visitors, Ferrante is expanding the winery to accommodate the increased business. The winery had to rebuild when a fire in 1994 claimed all but the original wine cellars. The company has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars over the years to keep up with changing technology and to replace its bottling equipment every seven to eight years, Ferrante says.

Cellar master Calin Lechintan has been with the company 18 years. In that time, production has increased to about 55,000 cases annually, up from 40,000, he says. Workers bottle some 2,000 gallons of wine daily for about three to four hours, and spend another two hours before and after the bottling to clean and sterilize the equipment.

“It’s for the stability of the wine,” Lechintan says. “If it’s not sanitized, you can have problems with the wine after it’s bottled.”

Ferrante distributes widely – its wines are available in the Mahoning Valley, but only a few varieties are for sale here. Much of the stock is only available at the winery. Now through August is the busiest bottling season, which leads into the harvest season in September through November.

Most grapes are harvested mechanically, but the 2017 pinot noir vintage was picked by hand, says Marketing Director Alyssa Ollis. It was an experiment, she notes. The grapes were clipped and cold soaked “to see if we could get a little bit more color from the grapes initially, prior to skin fermentation,” she says. “So far, it’s worked exceptionally.”

Ollis expects that wine to be released in spring of 2019.

Pictured at top: The Business Journal’s Michael Moliterno (left) and Jeremy Lydic (far right) met Alyssa Ollis and Carmel Ferrante at Ferrante Winery, along with Scott Dockus, Diana Maliqi and Judy Nagel of the Lake County Visitors Bureau.

Watch Our Ohio Wineries Video Series!

Tasting Notes: A Tour of the Grand River Valley (VIDEO)

Wine Grows Into Big Business (VIDEO)

Ohio Wineries Harvest $1.3B in Tourism Annually

Working Together Bears Fruit for Ohio Wine Industry

‘3 Minutes With’ Arnulf Esterer, Markko Vineyard in Conneaut

‘3 Minutes With’ Danielle Didonato, Laurello Vineyard in Geneva

‘3 Minutes With’ Cindy Lindberg, Grand River Cellar

‘3 Minutes With’ Eric Frantz, The Lodge at Geneva

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.