Business Journal Classic: Phar-Mor Reorganizes as Monus Goes to Prison

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – The cover of the MidAugust 1992 edition of The Business Journal declared “Phar-Fall.” It was accompanied by a photo of what appears to be an impassive Michael I. “Mickey” Monus, his face betraying no sign of the turmoil likely going on inside his head.

The story elaborated on what had only been hinted at in our August 1992 edition, which reported that Monus had been stripped of his roles as president and chief operating officer of Phar-Mor Inc. and demoted to vice chairman of the drugstore chain he had launched barely a decade earlier.

That edition’s top story – “Monus Confidant: Everyone Knew Everything” – outlined a wider-ranging conspiracy than Phar-Mor officials initially claimed.

A news release, distributed Aug. 4, 1992, by Phar-Mor accused Monus and Patrick Finn, dismissed as chief financial officer, of “criminal activity” in a $350 million fraud and embezzlement scheme. That included at least $10 million that had been diverted to the World Basketball League that Monus founded, and his Youngstown Pride basketball team – which also owed more than $55 million to Youngstown State University.

Said a source familiar with the inner workings of the company, “…I know for a fact that everybody at Phar-Mor, including [CEO] David [Shapira] on down, knew exactly what went on and what was going on. And right now they’re just trying to cover their asses.”

According to the company’s news release, “Among the irregularities, Phar-Mor’s investigation uncovered evidence indicating that financial statements were altered to conceal losses to overstate income. There is also evidence that Monus, with Finn’s assistance, diverted company funds for his personal use.”

So it was that the fall of Phar-Mor began, starting with the company writing off $350 million. Still, Phar-Mor remained a “strong company with a net worth of $220 million,” Shapira said in the release.

“To say that the actions of two former officers of this company were outrageous and shocking does not begin to convey my feelings. I intend to return Phar-Mor to profitability as soon as possible and to re-establish honest relationships with our banks and our vendors,” he vowed.

“My one consolation in all of this is that this fraud was limited to a few members of senior management and that overall Phar-Mor has extremely competent and honest employees operating the company.”

Immediate Impact

Construction was halted on a mansion Monus was building in Vienna Township as well as on what was to be a new flagship store in the then-new Shops at Boardman Park. More than 500 workers at Phar-Mor’s Tamco Distribution subsidiary were laid off, and 100 were let go from the Phar-Mor headquarters in downtown Youngstown. Next came store closings and severing the chain’s relationship with the Ladies Professional Golf Association.

Krista’s, a boutique that Monus’s wife operated in Boardman, removed its merchandise from a storefront location at the downtown building.

When Phar-Mor fired and sued its external auditors, Coopers & Lybrand, the New York accounting firm fired back.

“This whole affair is unusual and apparently designed to posture, bluster and transfer blame,” the firm’s deputy chairman and general counsel, Harris Amhowitz, said Aug. 5, 1992. “Phar-Mor is a closely held non-public company in which the owners, managers and the board are closely allied. Collusion and fraud at the senior management level did not occur in a vacuum.”

Media interest in the scandal was widespread. Phar-Mor spokeswoman Carol Robinson estimated that she had done at least 70 interviews per day with media outlets over a three-day period after news broke of the fraud and embezzlement.

Our editorial in the MidAugust 1992 edition, headlined, “Phar-Mor Scandal Rocks Region,” urged Monus to step down as a member and chairman of the Youngstown State University Board of Trustees, which he did Aug. 14.

“As a result of the accusations which have been raised against me, I would not in any way want to tarnish the reputation of this fine university for which I have worked so hard and accordingly, until I clear myself from these accusations, I believe that it would be in the best interests of this university that I not participate in its board of trustees,” Monus wrote in his resignation letter.

“I hope that upon my vindication I will have an opportunity to serve the university and my community in the not-too-distant future,” he concluded.

Legal Proceedings Begin

In a lawsuit filed Aug. 18, 1992, in Allegheny County Common Pleas Court, Phar-Mor accused Coopers & Lybrand of negligence and professional malpractice.

Coopers countersued, alleging that Monus and Shapira operated Phar-Mor “as a criminal enterprise,” claims that Phar-Mor countered as “false and wholly unfounded.” The auditors’ lawsuit also attempted to raise questions regarding John Antonucci, Monus’s partner in the Colorado Rockies, and Phar-Mor’s dealings with Antonucci’s Superior Beverage Group.

Phar-Mor and Coopers eventually reached a settlement. The terms were never disclosed.

By September 1992, Phar-Mor had filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and contracts were severed or sharply curtailed with businesses operated by Monus associates. One them was David Karzmer, a merchandise broker who owned one company that sold Phar-Mor diapers and health and beauty products, and another that supplied jewelry.

As the scandal unfolded, not everyone was convinced Phar-Mor was finished. Said an executive with greeting card supplier Gibson Greetings Inc. – which Phar-Mor owed nearly $6 million, the retail chain comprising 13% of Gibson’s business – “I’d like to believe if you build a $3 billion company, there has to be something legitimate there.”

Even Judge William T. Bodoh, who was overseeing the Chapter 11 case, was optimistic.

“I know of nothing at this early stage of the case that the company will not be able to reorganize its business affairs,” Bodoh said.

To guide the recovery, Phar-Mor enlisted turnaround specialist Antonio Alvarez, initially as acting chief financial officer and later named president and CEO.

Phar-Mor submitted its first debtor-in-possession financing plan to Bodoh’s court Oct. 7, 1992. The company was proceeding with store closings following successful lease negotiations.

In November 1992, Corporate Partners L.P., which invested $200 million in 1991 to buy a 17% stake in Phar-Mor, filed a federal lawsuit that claimed Coopers & Lybrand acted “recklessly” in performing company audits. This lawsuit also named Giant Eagle Inc. and Shapira as defendants. It accused Phar-Mor of overstating income and inventory and understating liabilities as early as 1988 to show it was profitable.

Next came conflicts between Monus and Antonucci over Superior Beverage and the Colorado Rockies expansion Major League Baseball team they helped to launch. Antonucci ended up being dismissed as chairman and CEO of the Rockies in what was described as an “office realignment.”

November 1992 also brought revelations about the serious damage that outstanding loans to Phar-Mor by Dollar Savings & Trust Co. had on its parent company, Ohio Bancorp, which recorded a third-quarter net loss of $11.3 million. A subsequent rushed deal to sell Ohio Bancorp to PNC Financial Corp. fell through. (National City Corp. would purchase the Youngstown bank in April 1993.)

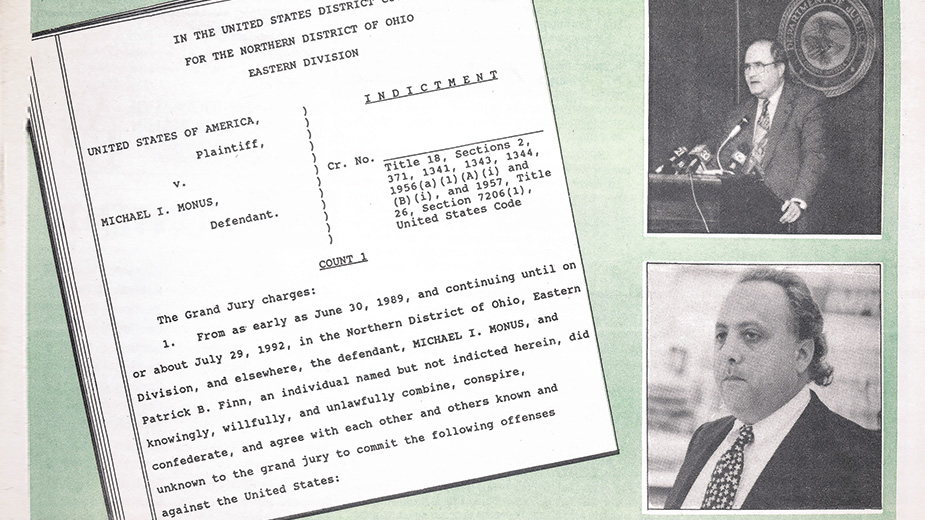

On Jan. 29, 1993, the U.S. Justice Department dropped the hammer.

Assistant U.S. Attorney John Sammon announced that a federal grand jury had handed down a 129-count indictment charging Monus with committing a $1.1 billion fraud. The counts included bank fraud, wire fraud, money laundering and falsifying tax returns. Also charged were Finn and another former vice president.

“I want to assure you when you see the word ‘billion’ in the press release, it’s not a misprint,” U.S. Attorney Patrick Foley told reporters, underscoring the significance of the case. “None of us can remember the word billion ever being used before in a fraud case.”

Monus pleaded not guilty Feb. 11, 1993. His first trial would end June 23, 1994, in a mistrial. He would subsequently be charged – and acquitted – of jury tampering.

On May 26, 1995, Monus was convicted on 109 counts of fraud and embezzlement. He served 10 years in prison and today resides in Florida.

For a time, Phar-Mor survived.

At a June 1993, employee meeting, Phar-Mor CEO Alvarez declared “the beginning of a new Phar-Mor,” even as he recapped decisions to reduce the number of stores, cut expenses in half and reduce revenues by a third. An ad campaign focused on the chain’s pharmacy operations – the largest aspect of its business – promoted the “Phar-Mor Promise,” which guaranteed to pay customers $10 if they could buy a prescription for less at another store.

Alvarez said he anticipated a mid-1994 exit from bankruptcy. “There were a lot of doubters who didn’t think we would be around today,” he said.

After emerging from Chapter 11, Phar-Mor endured a series of changes in majority ownership. In September 2001, it filed Chapter 11 for the second time. A liquidation plan was approved in June 2008.

NEXT EDITION: Doomed from the start. The Phar-Mor series concludes with the findings of the federal examiner, Jay Alix & Associates, appointed by Judge Bodoh in 1993.

Pictured at top: The bottom half of the February 1993 front page of The Business Journal shows the indictment, the U.S. Justice Department announcement and Monus.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.