Business Journal Classic: Tumultuous P. J. Schmitt Project

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – The Peter J. Schmitt Co. grocery distribution center in North Jackson that opened in 1989 amid much hoopla – and much controversy – operated for just a few years. The building, which today houses a much expanded fulfillment center for Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s, would herald the development of western Mahoning County into a warehousing and distribution hub.

But first came the turf war.

“Signed, Sealed, Almost Delivered – Schmitt Distribution Center Is Coming to North Jackson,” declared the front-page headline of the May 1989 edition of The Business Journal. Seneca, N.Y.-based Schmitt had executed a land option for 121 acres in North Jackson, where it had planned to construct a 600,000-square-foot grocery distribution center, the story reported.

Still, company officials were declining to comment on whether a final decision had been made in favor of the North Jackson site or instead to build on land in Mercer County, Pa. And when Supermarket News reported that the distribution center would be built in North Jackson, then-U.S. Rep. Tom Ridge of Pennsylvania responded by contacting company officials who, he told reporters, assured him that a final decision had not been made.

Among the local officials leading the charge for the Mahoning County site was then U.S. Rep. James A. Traficant Jr., who was telling area banks to loan Schmitt $7 million for site improvements and other costs.

“At this point, I’m urging the company, regardless of any local loan, to dip into their revolving fund, if necessary, and develop the project in North Jackson,” Traficant said.

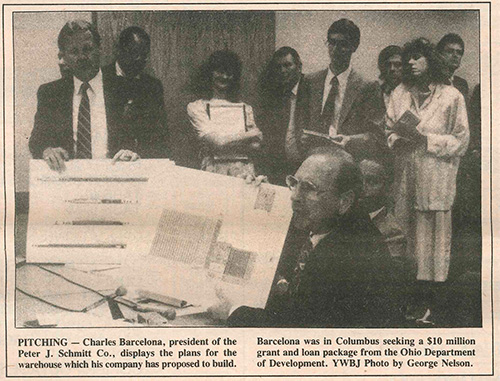

At the time, June 1989, Peter J. Schmitt was seeking a $10 million loan-grant package from the Ohio Department of Development, which company president Charles Barcelona said was essential to move forward with construction of the 567,000-square-foot warehouse. He contended the project would be dead if Schmitt didn’t receive approval soon.

That loan-grant package would lead to contentious hearings in Columbus. On May 25, 1989, members of the Ohio Development Finance Advisory Board questioned what they saw as a lack of collateral and security for the loan and were concerned that private investors would be repaid first if Schmitt went out of business. Akron area state Reps. Cliff Skeen and Thomas Seese focused on the impact the project would have on workers at the Schmitt warehouse in Akron, one of two that would be consolidated at North Jackson.

“It’s very, very difficult to explain to 225 employees that you’re using tax dollars in the state of Ohio to take their jobs away,” Skeen said.

Barcelona responded that Schmitt would deal fairly with workers, and that consolidation was better than the alternative. The warehouses in Akron, Youngstown and Sharon, Pa., which also would be merged at North Jackson, are obsolete, he said.

“If we would allow our Akron plant to close and just go out of business, these people would have no real separation opportunities, no transfer opportunities. They would be out of work – period,” he warned. “We break even at best in Youngstown and Sharon, and we lose money in Akron.”

The Ohio Controlling Board ultimately approved a $9 million loan package with the possibility of a $1 million state grant contingent on funding availability.

The approval came despite the concerns raised May 25, 1989, at a meeting of the Development Finance Advisory Board and a subsequent meeting June 9. Board member John McFadden questioned the “very high public participation in a private enterprise deal” as well as job creation “that is such that we have not brought before us before, where we have bona fide jobs created in new industries.”

At one point during the hearings, Barcelona declared, “The best security that our lenders can have is the quality of the company and its business.”

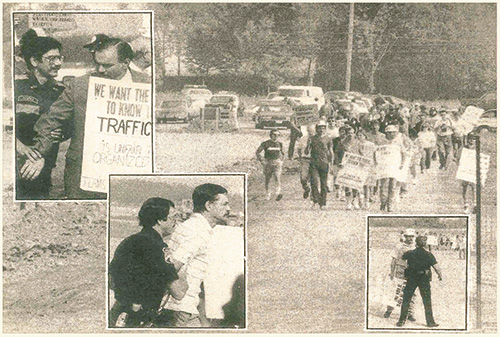

Schmitt moved ahead July 25, 1989, with a groundbreaking. But the celebration was delayed by the arrival of about 50 workers from the company’s Sharon operation to protest the wage agreement negotiated for employees at the North Jackson site. Four of the workers who had marched onto the property were arrested although charges were subsequently dropped.

By the first week of June 1990, less than a year after the groundbreaking, the new distribution center was shipping product.

“That is a phenomenal timetable,” Gary Sanders, Schmitt vice president of human resources, observed in our September 1990 edition.

Barcelona’s statement in 1989 about lack of profitability would come back to haunt Schmitt – and the Valley – within three years, when the warehouse sat shuttered, leaving some 500 jobless.

“For the past two years, our Tri-State Division has generated losses at a level that threatens the viability of the entire company,” an unidentified Schmitt spokesman said, according to the MidJune 1992 edition of The Business Journal

Indeed, the company ended up filing for bankruptcy reorganization, and a month later the warehouse was being marketed by a task force that included Holly Hill Oelslager, Ohio economic development representative. In July 1992, she showed the vacant distribution center to one of the companies that had expressed interest.

At one point, Akzo Salt Inc. was negotiating for the property, we reported in January 1993.

Eventually the building would be acquired by Kaufmann’s and used as a regional distribution center that employed 400. It was retrofitted with high-speed sorting, conveyor systems, high-bay storage and voice recognition technology systems, according to our MidJuly 1995 edition.

Retail mergers over the intervening years would result in Kaufman’s stores adopting the Macy’s name, and the distribution center changing its name to Macy’s as well. In June 2007, The Business Journal reported on plans to add 18 loading docks and make other upgrades, assisted by a 57% property tax abatement over eight years approved by Mahoning County Board of Commissioners.

“It positions us for future growth,” said Christopher Williams, Macy’s vice president of distribution.

The company would continue to expand at the North Jackson site.

In February 2021, Macy’s Corporate Services LLC announced plans to expand the building to accommodate a fulfillment center that would support its growing digital business for the Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s chains. The plan included a $29.9 million capital investment that would add 417 jobs and retain 55. Earlier, the Ohio Tax Credit Authority had approved a tax credit.

“It’s an important win for that facility,” Walt Good, managing director of projects for Team NEO, said in 2021. “It solidifies that footprint in the Macy’s portfolio of operations.”

Added the CEO of Team NEO, Bill Koehler, in a statement announcing the project, “The North Jackson/Lordstown corridor has witnessed impressive announcements in the past several years with seven companies committing to create more than 5,200 new jobs.”

Macy’s announcement of its $29.9 million expansion at the original Schmitt site featured laudatory statements from a Jackson Township trustee, representatives of the Ohio Development Services Agency and what became the Youngstown/Warren Regional Chamber in 1993 with the merger of the Youngstown, Warren and Niles chambers. Also lauding the project was the Western Reserve Port Authority, created in 1992 and subsequently given the funding and tools to promote economic development across the Mahoning Valley.

It was noted that the $29.9 million project came together relatively quickly thanks to the collaboration of local and state development officials and agencies.

“That led to a lot of infrastructure developments out there,” says David Wilaj, director of the Mahoning Valley Logistics Council.

Extrudex Aluminum subsequently built a factory in North Jackson and FedEx located a distribution center there as well. This led to additional infrastructure improvements, which made it easier for trucks to reach Interstates 76 and 80. “It kind of exploded from there,” Wilaj says.

Today, companies in the distribution space continue to look at the area, and the Ohio Site Inventory Program is providing assistance for development of “spec” buildings such as one for the 45-acre industrial park envisioned near the Macy’s distribution center.

“Our plan is to put a road in through the property and we’ll have basically five lots that can each hold up to a 100,000-square-foot building,” developer Greg Toporcer said in July 2024.

Top Property Holdings LLC plans to invest $7.5 million and begin construction this fall on the first building at the site, 13001 Mahoning Ave., according to Toporcer.

“The region is getting strong looks by national and international companies exploring where to invest and it’s critical that we have a supply of marketable buildings and sites,” he said.

Pictured at top: The recently expanded Macy’s Bloomingdale’s Fullfillment Center is on the site of the original Schmitt warehouse. Inset: Dan O’Brien drew this political cartoon published in our MidJune 1989 edition.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.