City Club Panel Seeks Collaboration to Close Wage Gap

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – A quarter of employed adults are in jobs that, even with full-time year-round work, don’t pay enough to lift a small family out of poverty.

Addressing that wage gap locally requires a collaborative approach that involves the business community, public sector and nonprofit community organizations, members of a City Club panel said Thursday night.

During a discussion hosted by the City Club of the Mahoning Valley, Maureen Conway, vice president for policy programs and executive director of the economic opportunities program at the Aspen Institute, recalled the experience of a black man who was struggling personally at the same time he was succeeding in a job-training program. The man, after his initial reluctance, finally said he all he wanted from the program a chance.

“We have an opportunity through public sector, private sector, civic and social institutions working together to really give that young man and millions of young men and young women like him to get their chance to work for the American Dream,” Conway said.

Conway was the speaker at “Closing the Gap: Building Opportunity in the Valley.” She was joined by panelists Denis Robinson Sr., mission services director for Youngstown Area Goodwill Industries Inc., and T. Sharon Woodberry, director of community planning and economic development for the city of Youngstown. Andrea Wood, publisher of The Business Journal, moderated the discussion.

Other challenges Conway outlined include more people struggling with the costs of even meeting basic needs, as some 40% of American households would be unable to come up with $400 in case of an emergency expense.

“It is important to note that these economic challenges are not equally distributed,” she said. Low-wage workers are far more likely to be women or people of color.

While the gender gap has narrowed, women still earn 85% of what men do, according to a Pew study. Unemployment among blacks is about double that of whites, even when accounting for education levels, and the typical black family has 10% of the wealth as the typical white family.

Some of the changes are because of the shift from an economy based on manufacturing and production to one based on services, which had a “disparate impact on different communities,” she said.

She pointed out that the wage gap issue isn’t limited to the Mahoning Valley, as the changing nature of work has hollowed out family-wage jobs across the country.

A map of the communities that qualified for the new federal Opportunity Zone program reveals rural, urban and suburban communities that have disproportionately higher poverty and unemployment rates, lower levels of education and less access overall to economic opportunity – “a map of the unequal access to opportunity across America,” she said.

“We can change this picture. If we don’t like the fact that working people can’t support themselves on their earnings, we can change that,” she continued.

Based on her studies of workforce development and sector partnerships, Conway said building networks among companies in an array of sectors is important, as is understanding the barriers to employment that exist and thinking about how to address those barriers so workers can stay in programs that provide them with the skills to succeed.

“There has to be a level of connection with social services and other community-based programs,” Goodwill’s Robinson said. “We can’t just create these plans and create these opportunities and say, ‘Go.’ … There has to be some hand-holding and we have to be willing as sector partners to do that.”

Several organizations and agencies exist that provide “some component of what is needed,” Woodberry said.

“Where we can gain some traction is when you’re helping to connect those, making it easier for the job seeker and also the employer,” she continued.

As employers seek workers with the skill sets needed for jobs, the public sector has a role in providing training to make it easier for individuals who can fill those needs.

“It’s happening locally. It just needs to happen on a much larger scale,” Woodberry said.

More employers are partnering with organizations on projects like designing jobs and identifying factors that are preventing employees from succeeding in the workplace, Conway said.

“Many people don’t want to tell your boss what the problem is. Some of these organizations can be helpful intermediaries,” she said.

Conway pointed to a nonprofit in Grand Rapids, Mich., The Source, that goes into workplaces and informs workers of resources they might be eligible for such as food stamps, child care subsidies and other public benefits or, for those who are above eligibility thresholds, charitable resources in the community.

The organization also provides workers with help in handling emergencies such as a car breaking down or a sick child needing day care.

The employer pays most of the cost because it reduces turnover, which is often more expensive in the long term than the services provided.

“It’s a really helpful way to help people stabilize and stay in their work, and the longer you can stay in a job the longer you can grow in a job,” she said. “You don’t have the opportunity to grow in a job if you go in and out of work and are not able to stabilize.”

Transportation is one of the largest barriers to stable work, Robinson said. He recounted how one employee Goodwill had placed in a job was consistently late for work, but still arrived at the same time every day. The employee took the earliest bus he could but it still dropped him off far enough away that he was late, even though he ran the rest of the way.

Goodwill worked with the company to get the worker’s start time changed. Not only was he able to keep the job, but he was eventually able to get a car.

“It’s also important to look at the reason transportation is an issue,” whether it’s the car itself or a driver’s license, Woodberry said.

In some cases, a worker might pass on an offered promotion if the loss in a benefit the worker receives outweighs the boost in pay, Conway said.

During the question-and-answer period, Jessica Borza, executive director of the Mahoning Valley Manufacturers Coalition, asked Conway what organizations could do to build capacity and support efforts to build partnerships.

“Every organization has limited capacity in some sense,” Conway said. One way they can maximize capacity is building awareness among organizations to work better together and leverage resources.

“You also do need to grow the number high-quality jobs” and think about how to influence the labor market to do that, she continued.

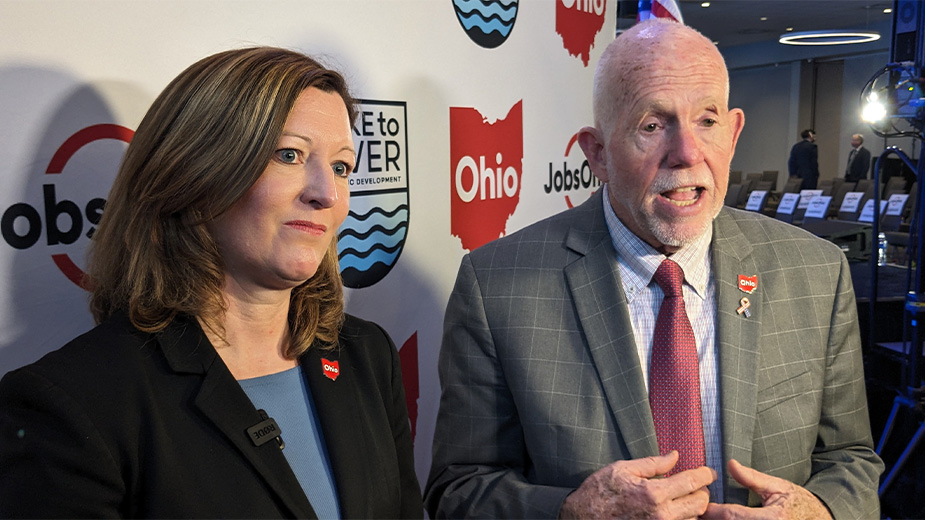

Pictured: In a panel moderated by The Business Journal publisher Andrea Wood, T. Sharon Woodberry, director of community planning and economic development for the city of Youngstown; Denis Robinson Sr., mission services director for Youngstown Area Goodwill Industries Inc.; and Maureen Conway, vice president for policy programs and executive director of the economic opportunities program at the Aspen Institute, discussed how to employers can work to close the wage gap.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.