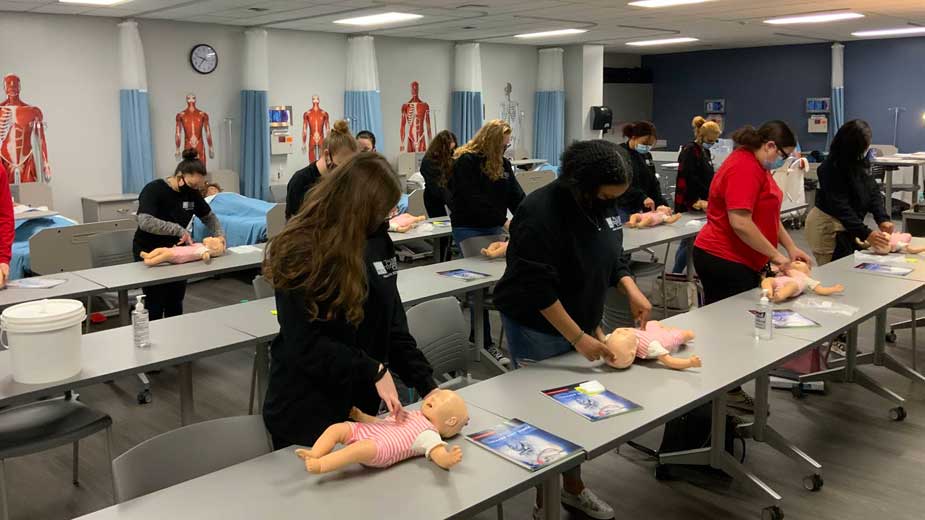

Connecting Nurses with Careers Starts in School

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – With a booming local health-care industry, county technical schools and Eastern Gateway Community College have become a pipeline to direct students into the field. A core component of students’ education is ensuring that they’re ready to apply what they’ve learned to the real world.

That means they know how to place IVs. They know how to communicate with other medical staff. They have a foundation to build on.

“If I can teach the basics before they’re in the workforce where they have to be more intricate with the policies and procedures that each institution has, it makes the transition into the job easier,” says Barb Meyer, an instructor in the prenursing program at Trumbull Career and Technical Center. “

For the schools educating future nurses, their curricula are intertwined with the employers that students will work for after graduation. All three have advisory committees – across most fields, not just medical education – that provide feedback on what students are learning in the classroom and on their clinical rotations. That feedback, says Eastern Gateway vice president of academic affairs John Crooks, is melded with the curriculum requirements from state agencies.

“I’d be remiss if I said there aren’t things we need to tweak. Higher education always has to listen better and see what we can change,” he says. “We try to implement those [suggestions] because if some of these students are basically interviewing during their clinical experience, why make it more difficult for them?”

At Columbiana County Career and Technical Center, licensed practical nurse program director Carolyn McCune says some of the biggest additions made to the program because of the advisory committee have been education on electronic health records – a must in today’s digital world – and how to properly call a doctor when there’s an issue with a patient. Something like that, she says, is likely not considered by most people when they set foot in a nursing classroom, but it’s still an important part of getting students ready for a job.

“If you’re a nurse working midnights and a patient refuses medication, a doctor’s not going to be happy if he gets a call in the middle of the night. If a patient falls, the doctor is going to want to know their blood pressure, their heart rate and how they look,” she says. “We try to roleplay that and get them thinking beyond ‘I’m going to call the doctor.’”

The employers serving on the advisory committees are also some of the sites students will do clinical rotations, providing an extra layer of feedback to ensure schools are producing job-ready nurses. At Trumbull Career and Technical Center, students are required to do 20 hours of clinical work at area nursing homes. That work, says prenursing instructor Barb Meyer, often serves as a prolonged interview for students, allowing facilities to see how the students work and deciding if they’re a good fit for the workplace.

“There are plenty of conversations where they say, ‘Once [this student] is done, please send them our way,’” she says.

Plus, it’s a chance for students to see if the field is a good fit for them. There can be a stark difference between in-classroom reading and in-person application. Learning about that distinction early on can help students better understand the rigors of a medical career.

“It’s an eye-opener for them and let’s them figure out if they like the work and the facility. We start with where they do their clinicals and supplement that in the classroom by talking about long-term care facilities where they might be able to go,” Meyer says.

In many aspects, the clinical part of nursing education is the most vital. Students who don’t pass their clinical courses can’t sit for their licensing exams. Those spaces, Eastern Gateway’s Crooks says, give students a chance to learn soft skills, which can be the hardest to develop and are vital in life-or-death situations that come up in the medical field.

“They have to communicate with physicians. They have to communicate with colleagues. They have to communicate with patients. They have to communicate with people who may not have English as a first language,” he says. “The culture and expectation is that you won’t just have the knowledge base with technical skills, but that you can interact appropriately with patients. If someone has a strong enough desire, it’s amazing how rough people think they are but have this amazing transformation.”

At the Columbiana County Career and Technical Center, high school instructor Pamela Dawson says students often gain extra experience by working in health-care settings while in high school. Through the CCCTC program, students can become state-tested nursing assistants after their junior year. Before their senior year, students can choose between continuing their education in either the EMT or patient-centered care programs. The technical centers also offer nursing education programs for adults. The two tend to cover similar ground, but with an extra layer of critical thinking.

“There’s a lot more content and a lot more critical thinking as these students get older and get more education. The biggest challenge for me is that critical thinking piece. We can teach them all the pieces and parts, but [students] have to put them together to make decisions,” she says.

That education, Dawson says, has put students in high demand at local health-care centers.

“As far as my students, many of them are already working in the health-care field. Anyone that wants to work is working, either as PCAs or STNAs as seniors in high school,” Dawson says. “For the long-term care facilities in the area, this is about the time of year they start calling to recruit some of our juniors. There are no problems placing our kids.”

Pictured: Nursing students at Trumbull Career and Technical Center practice CPR. A core component of nursing education programs is developing skills students will use on the job.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.