Shell Cracker Plant’s Reach Heads this Way

MONACA, Pa. — Two backhoes lift loads of dirt on a section of 100 acres in northern Beaver County, Pa., where the first signs of new development along the Interstate 376 corridor are visible.

Much of the land – an expansive parcel next to the Turnpike Distribution Center in the borough of Big Beaver – has been cleared to allow construction of the first of three buildings that will encompass one million square feet of distribution space.

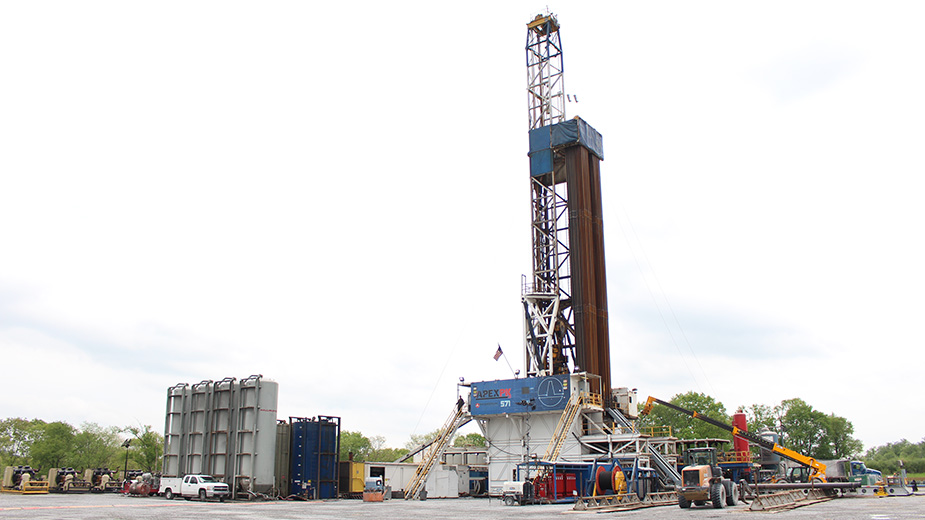

Just 15 miles directly south, near Monaca, Pa., along the Ohio River, hundreds of construction workers swarm the 600-acre site where Royal Dutch Shell is constructing its $6 billion ethane “cracker” plant.

The project is a mammoth undertaking that should employ nearly 6,000 tradesmen during the building phase and 600 full-time employees when it becomes operational in the early 2020s.

Both developments are linked by I-376, a thoroughfare likely to become the focus of commercial interests as this region emerges as a player in the plastics and petrochemicals industry, anchored by the Shell project.

“We’re very encouraged, very optimistic,” says Pat Nardelli, a principal at Castlebrook Development Corp., which is developing the Big Beaver site. “We’re all excited for the entire region, and this includes New Castle and Youngstown,” he says.

On this site in Big Beaver, Pa., Castlebrook Development Corp. plans to construct three buildings to house cracker-related warehouses and industrial companies.

On this site in Big Beaver, Pa., Castlebrook Development Corp. plans to construct three buildings to house cracker-related warehouses and industrial companies.

The company’s new project abuts a development Castlebrook opened eight years ago – the Turnpike Distribution Center – at the I-376 and I-76 interchange. With the Shell cracker plant moving forward, the conventional wisdom holds that the complex will eventually attract more manufacturers or processors in the plastics and petrochemicals industries along with additional service-related companies to the region. That means demand for distribution space is likely to increase, he says, and Castlebrook has staked out an ideal position in this corridor.

“We thought that there would be a need,” Nardelli remarks. “There’s quite a bit of interest.”

Still, raising capital for such a speculative project is difficult despite the allure of the Shell cracker. In this case, the $9 million distribution center was helped through the Power of 32, a $49 million regional venture fund spearheaded by the Allegheny Conference on Community Development and a consortium of 14 financial and development partners. The loan fund identifies development sites across 32 counties in Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia and a segment of northwestern Maryland. To date, the program has funded four projects.

Castlebrook secured $6.8 million in financing from the program, Nardelli says. “We then raised some equity and we’re under construction,” he continues. “We’re about three weeks away from the first pad. It couldn’t have been done without the Power of 32 fund.”

The Castlebrook project could be a hint of what lies ahead for this region as the Shell project and other oil and gas-related efforts materialize, officials say. Opportunities for the building trades alone should balloon while oil and gas exploration and production from the Marcellus and Utica shale plays in Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia stand to stabilize and grow.

Once in operation, the Shell plant would consume ethane, a liquid gas found in abundance in the Marcellus and Utica shale. The plant then converts the molecules into ethylene and polyethylene – which are used as a base ingredient for plastics and thousands of other products.

“We have about 60 members working at the Shell site right now,” reports Ken Broadbent, business manager with Steamfitters Local 449, whose territory encompasses 15 counties in western Pennsylvania stretching from the West Virginia border to Lake Erie. “Right now, they’re just doing the underground work.”

But when actual construction of the plant begins in earnest next year, the demand for fitters and welders is sure to increase substantially.

What concerns Broadbent is the possibility of insufficient welders in the field to meet this growing demand – not just for the cracker, but other oil and gas-related projects that may arise over the next two decades. “You have to look 20 years down the road,” he says. “If there are more plants, like plastics facilities, we want to train the people who live and work here.”

Steamfitters Local 449 recently hosted an open house at its training center in Harmony Township, Beaver County, Pa., to gauge interest in welding careers. The turnout helped allay some concerns because more than 360 from Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia attended and signed up for a preliminary mechanical aptitude test. “I ordered food for about 150,” Broadbent says and laughs. “I probably fed about 450. Some were accompanied by family members.”

The open house attracted interested parties from East Liverpool in Columbiana County and a sizeable number of students from the New Castle School of Trades. “We communicated with all of the tech schools, and had them email students about the open house,” Broadbent says.

As demand for workers in the energy industry intensifies, it’s imperative that a solid pipeline of new talent in this region be trained and prepared, the Steamfitters business manager says. That way, it ensures that craftsmen from this region perform the construction and trade jobs, not those brought in from oil and gas states such as Louisiana and Texas.

“With the amount of work in other natural gas projects – co-generation power plants, compressor stations, processing plants – we want that work to stay in the tri-state area,” Broadbent says. “We’re looking for motivated, determined people and these are exciting times,” he says.

Indeed, it makes sense to market this region as a whole, rather than pit communities or states against one another, says Linda Nitch, executive director of economic business development for the Lawrence County Regional Chamber of Commerce. The I-376 corridor runs through the entire county, connecting with Interstate 80 in Mercer County to the north and Pittsburgh to the south. Meantime, the Ohio River acts as a natural geographical bond for Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia, she says.

“We went to meet with Shale Crescent USA in Marietta, Ohio, to learn what they’re doing,” Nitch says. The organization, established two years ago, launched an initiative to encourage regional development along the Mid-Ohio River Valley, using the Marcellus and Utica as selling points.

The premise is to market the region much as the Gulf Coast does for the petrochemicals industry. “It makes sense to think broadly in regional terms,” Nitch says.

PTT Global Chemicals, a petrochemicals giant based in Thailand, is assessing whether to build a multi-billion dollar ethane cracker in Belmont County, Ohio, along the river. A decision on that project is expected by the end of the year.

Meantime, utilities such as FirstEnergy are doing what they can to promote the area, Nitch says, adding that company representatives plan to attend a major plastics exposition in Orlando, Fla., next year to tout the cracker complex and its benefits.

Nitch is especially interested in marketing the I-376 corridor, although she says no imminent new projects in Lawrence County are related to oil and gas.

Still, oil and gas production in Lawrence County is inching upward again, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. The county boasts two major energy companies with active wells – Hilcorp Energy Co. and R.E. Gas Development, a subsidiary of Rex Energy.

For the three months ended May 31, Lawrence County reported 58 horizontal wells in operation that collectively produced 7.350 billion cubic feet of natural gas, according to the DEP. In May, those wells yielded 2.43 billion cubic feet of gas, an increase from 2.36 billion cubic feet the previous month.

Hilcorp owns all but 10 of those wells, data show, R.E. Gas the rest.

“I’m hearing that royalty payments to some landowners are getting a little bigger,” Nitch says. “Hilcorp must be pumping up their distribution of gas.”

Permits for new wells across the county, however, have slowed. According to DEP data, it has issued no permits for new horizontal wells this year. The five permits issued were either renewals or modifications of existing permits.

Oil and gas activity is also measured by the funds the county receives each year in impact fees, says Lawrence County Commissioner Dan Vogler. This year, the county received a $50,000 check from impact fees, based on the quantities of oil or gas produced from Pennsylvania’s wells. That amount, however, was based on 2016 production levels, when oil and gas companies were pulling back on production.

“I would say production is fairly stable,” Vogler says, noting most wells in Lawrence County lie within in Pulaski and Mahoning townships.

As for the impact Royal Dutch Shell’s project is having on Lawrence County, Vogler says that he’s spoken with representatives of local trade unions who say their members are busier than ever.“They’ve seen an uptick in members working at the cracker,” he says. “Their folks are busy, and we remain very hopeful.”

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.