Flashback: Remembering Jim Crow in Youngstown

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – The images from the 1960s of the civil rights movement remain vivid: photographs and TV news footage of marchers trying to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge at Selma, Ala., police siccing German Shepherds on protestors in Montgomery, Ala., and Martin Luther King Jr. delivering his “I Have a Dream” speech.

In Youngstown, the images of the civil rights movement are less known. But for those who lived through it over the decades, they are just as vivid.

Nathaniel Jones, a retired federal judge, remembers trying to desegregate the city’s pools and being met with violence. Mel Watkins, former editor of The New York Times Book Review, looks back at being barred from restaurants and certain areas of movie theaters.

Al Bright, an artist and retired professor at Youngstown State University, recalls being kept out of a city pool by its manager while the rest of his baseball team was allowed to swim. For the Rev. Ken Simon, the image never fades of armed guards stationed outside his family’s home after a bombing.

Jones’ involvement in civil rights began in the 1930s at the segregated West Federal YMCA. Each winter, he recalls, speakers from around the country came to the building, now home to Rescue Mission of Mahoning Valley, to talk about what was happening in regards to civil rights issues such as education, hiring and housing.

“When I was about 9, [my mother] took me to hear one of the speakers and I went for several years after that,” Jones begins. “I developed a keen interest in the issues they discussed. And I learned these issues were not limited to Youngstown.”

Between 1910 and 1920, the black population of Youngstown rose to 6,662 from 1,936 as the United States entered World War I and migrants from the South moved to the area to work in the mills. “In Youngstown, the push for civil rights really began in the 20s. It became clear that there was widespread segregation and discrimination in housing and restaurants,” Jones says.

By World War II, there were more than 21,000 African-Americans living in Youngstown.

In Westlake Terrace, the city’s first housing project and built by the Works Progress Administration, the races were segregated, with whites living on the north side of the complex and African-Americans on the south side. The dividing line, Bright says, whose family was one of the first to move into Westlake, was Madison Avenue and even within the African-American side, there was segregation, he adds.

“There was a color line at the time where the fair-skinned African-Americans lived on Federal Street near the Y, the brown-skinned lived in the middle and the darker-skinned were kept on the bottom part of the project,” he says.

In the 1940s, the city-operated swimming pools became of battleground for the civil rights movement. Of the six owned by the city, only one pool, in the McGuffey Heights neighborhood, was open to blacks.

Jones was part of a group who attempted to desegregate the North Side pool and was met by a mob. After the fighting settled, Jones and others were able to identify some of the attackers, resulting in several arrests.

In 1951, Bright had his own experience a city swimming pool that he points to as one of his first experiences with racism. That year, as part of the Donnell Ford Little League team, he hit the winning home run in the city championship game. To celebrate following the game, the team went to a city pool on the South Side. Bright, the only black player on the team, was prevented from entering the pool by the manager, who padlocked the gate to keep him out.

“It was a humiliating experience. I came up as a hero and ended up being a pariah when I got there,” Bright says. “When I refused the food, the team mother, Mrs. Mulligan, went to the manager and read him the riot act, to which he showed indifference to as well.”

Eventually, the manager let Bright into the pool but made him sit in a raft and not touch the water. After ringing a bell signaling all patrons to get out of the water, he walked Bright’s raft around the edge of the pool several times before kicking him out again.

“I stared everyone right in the eye. I didn’t show anger, but I wanted to make eye contact. And nobody had the courage to look at me. They’d lower their heads and look away because they were as victimized as I was,” Bright says. “I felt as bad for them as I did for myself because they were locked inside this situation. I was going to go back out of the pool and that made me freer than anyone inside.”

Simon, whose father the Rev. Lonnie Simon was a civil rights leader in the city, recalls his first experience with racism. One day after basketball practice at East High School, Simon stopped at a store to buy a soda. Before Simon could walk inside, the owner came out and told him the store was closed.

“I asked him why and he said, ‘If it’s closed, it’s closed,’ ” he recalls. “As I got to the corner, this white guy pulled up with his kid in the car and I watched him, waiting for the owner to tell him his store was closed. Turns out the store wasn’t closed.”

Watkins, who recounts his experiences in his 1998 book Dancing with Strangers A Memoir, says racism in the Mahoning Valley was less overt than it was in the South.

“When I got into my teens is when I realized that the schools there were segregated, the hotels were segregated. As you grow up, it becomes different. It was obvious in terms of male-female relationships, in terms of restaurants,” he says. “It was institutionalized racism that prevailed. Even if someone didn’t truly believe that, it still showed. You were told you were only good enough to work in a steel mill, which never was said to a white student.”

African-Americans were still confined to movie theater balconies here and barred from certain restaurants, he rememembers, but as a child the de facto Jim Crow practices didn’t affect him. He refers to one of his favorite Youngstown restaurants: Jay’s Hot Dogs.

“They were some of the tastiest hot dogs I’ve ever eaten, but [for African-Americans] they were bought outside and taken out,” he says.

As part of “concerted effort” by the NAACP, Jones says, Jay’s and several other downtown restaurants, including the Brass Rail and the Rainbow Grill, were integrated after the owners were threatened with arrest for violating Ohio’s civil rights laws.

When the city’s population began to slip in the 1960s and steel production fell in the 1970s, Simon says racism became more overt. When everyone has jobs, he explains, people are content and things stay under the surface.

“When the mills went down, you saw that resurfacing because the economics always expose it,” he says. “When resources are limited and jobs are few, then you see the attitudes of racism resurface.”

Simon remembers how his father participated in the marches from Selma, Ala., to Montgomery in 1965. It was the churches that led the movement in Youngstown, just as they did in the South, he says.

When Jones and others were met with violence when they attempted to integrate the city swimming pools, The Vindicator ran an editorial saying African-Americans had a right to use the pools, but it might not be in their best interest to try and do so, the retired judge recollects.

“On the heels of that, a priest at St. John’s Episcopal Church named John Burt challenged that notion in his sermon and a few other pastors took it up shortly after,” Jones recalls.

The newspaper changed its stance after condemnation from the black communities in the Mahoning Valley, he adds.

It was the early 1960s when the civil rights movement publicly began taking hold in Youngstown. Marches and protests downtown became more frequent, but rarely turned violent, Bright says.

There were, however, isolated incidents of violence, Simon notes, including a car bomb aimed at his family.

“For about a month after that, we had guys from Freedom Inc. – these militant kind of guys – who knew my father’s life was in danger and formed a little group,” he says. “When you’re dealing with social justice issues and taking a stand for rights, you get in trouble with society and branded as a troublemaker. He took that risk and stood up for what was right.”

In 1968, after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., riots broke out in the city. Lonnie Simon tried to calm the group that formed on Hillman Street, but violence eventually broke out between police and those assembled.

Mayor Anthony Flask ordered all available officers to the South Side and called in the National Guard. Eighty people were arrested.

Watkins had left Youngstown by that time but remembers, at least among his relatives and friends, there was a sense of dismay about the riots.

His sister lived on Delason Avenue at the time of the riots and “she talked about it as if people had gone crazy,” Watkins says. “She thought it was ridiculous to be burning. None of my family was involved and by that time my parents were in their 70s and most likely disturbed or angry that it happened.”

A second riot broke out a year later after a white storeowner was accused of hitting a pregnant black woman. At first the NAACP picketed the store, but days later another store on the East Side was firebombed. The violence spread across the city, including to Hillman Avenue. When fire trucks came to put out fires at businesses, they were attacked as well.

“It’s just pent up emotion baby, 100 years of being exploited and made to eat dirt,” said one person quoted in the newspaper.

In 1970, Bright helped start the African-American Studies program at YSU, one of the first in the state. Bright, along with several other faculty members traveled to other schools to see what they were teaching about black history. Over the course of his 18 years as head of the program, several African-American leaders came to Youngstown, including Roots author Alex Haley three times, Jesse Jackson, Maya Angelou and Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman to run for president.

“They interacted with the whole community and that information helped changed perceptions,” Bright says. “They opened up a dialogue over 18 years and made it so people were discussing the issues.”

In the time since, Simon, who leads the same church his father once did, points to the election of President Barack Obama as one of the biggest events in an ongoing civil rights movement.

“It was an energizer because there were people who never thought it would happen,” the pastor says. “He symbolized that transition that Dr. King talked about – that a man won’t be judged by the color of his skin but by the content of his character.”

It gave something for African-American children to aspire to. When Jones, Simon, Watkins and Bright were growing up, there weren’t many role models.

“Nobody had ever talked to me about going to college,” Bright says. “Everyone in my community at that time was, at best, working for the post office. I didn’t know what you’d even go to college for.”

Simon, who studied business at YSU, says he followed in his father’s footsteps because of the journey for civil rights. As a church leader, he says, he can interact with people – city residents and public officials – to try and improve the community he serves.

“There’s a need in the struggle for freedom, justice, equality and empowerment,” Simon says. “If you don’t empower your people, then you’re always at the whims of a system that doesn’t have our interests at heart. We’re empowering ourselves through education and controlling our own institutions.”

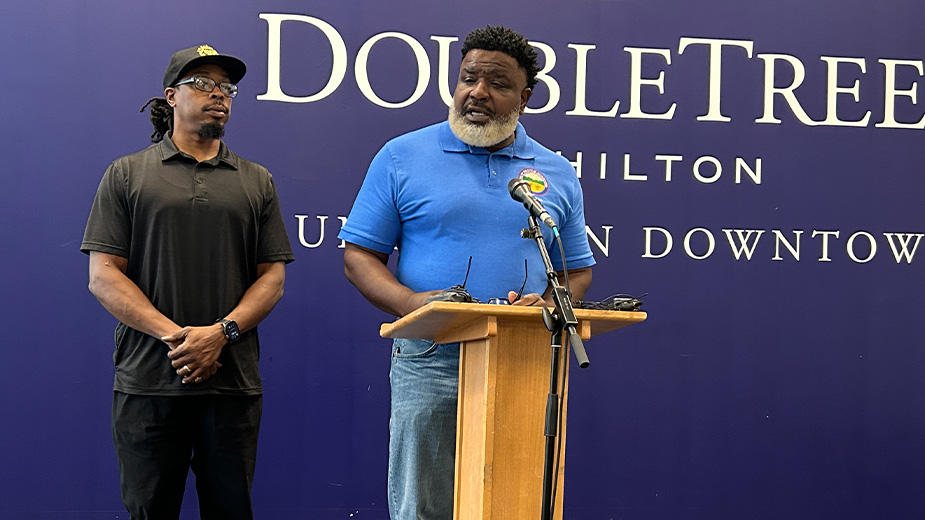

Pictured: After his team won the city Little League championship in 1951, Al Bright was barred from a public pool for the team’s celebration. He was the only black player on his team.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.