Flashback to an Extraordinary Life Well Lived

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — “Nach Sedan!”

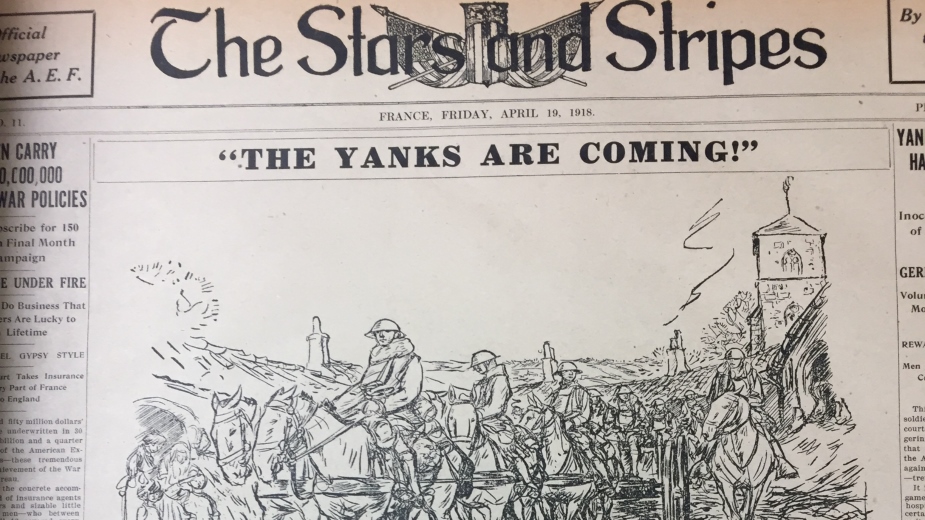

“So read the big crossroad signs that the advancing troops of the First American Army found along the mined and muddy roads that led northward to the west of the Meuse,” reported the Nov. 15, 1918, edition of The Stars and Stripes, the official newspaper of the American Expeditionary Forces in France during World War I.

These words, written 100 years ago this month, present an account of the waning days of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the final drive that broke the back of German resistance as Allied troops closed in nach, or near, Sedan, a town in northeastern France that had been occupied by Germany since the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.

“Nach Sedan! Every battalion commander, every cook, every doughboy, as he trudged along those highways had it in the bottom of his heart and the back of his mind that, come what may, he was going to Sedan,” the story continued. The lengthy article placed in context the importance of French forces retaking the city, and how American regiments – including an Ohio company – secured the outskirts of the town to pave the way for French reoccupation.

Stars and Stripes never used bylines in its publication, so the author remained anonymous. That is, until a municipal court judge addressed a group of army veterans six years later to commemorate Armistice Day in 1924.

“By good fortune, I was at the front for the last days of the Argonne Drive,” he told veterans, recounting details of how French and American forces lurched toward the city. “Now, by a strange turn of fate, the sons of those conquering German fathers were in full retreat – nach Sedan.”

The speaker that day was Joseph Heffernan, then a newly elected municipal court judge in Youngstown. Six years earlier, Heffernan was slogging through France as a war correspondent for Stars and Stripes and was with the First Army as it entered the outskirts of Sedan.

For many, the experience of a field correspondent during World War I would fill volumes and serve as a critical marker in anyone’s professional career. For Heffernan, it represents merely a chapter in a life that embraced a fascinating diversity of interests, intellectual pursuits, travel and accomplishments.

Heffernan was born in Youngstown in 1887, the grandson of Irish immigrants who ventured west to Ohio earlier in the century. He attended school in Youngstown, and then in Coitsville, where the family had moved after the panic of 1893. Heffernan then did what many of his generation were forced to do – he quit grade school to go to work.

That meant the steel mills. According to an autobiographical account that the judge started but never finished – now in the special collections archives of Youngstown State University Maag Library – his first job required 12-hour days at $1.25 per day. “Even at that age, however, there was a yearning for something better,” he wrote.

A biographical sketch of then Judge Heffernan, written by George M. DePetit, for a story in the Sunday Youngstown Vindicator in 1925 encapsulated the many sides of the man. He was a steelworker, joined a steam shovel gang in the Midwest, served as a galley cook on an Ohio River steamboat, was employed as a chef in some of the most stylish restaurants in Bridgeport, Ill., and spent time as an expert rivet heater on oil rigs in Illinois and Tulsa, Okla.

“If I were to tell you all the circumstances of those lean and hungry years, you’d hardly believe them,” Heffernan wrote. On one occasion, he was fired at a restaurant because he presumed — wrongly – that he could take a plate of turkey on Thanksgiving Day.

From there, he went farther west and snagged a job as a hotel clerk in Los Angeles, joined the workforce constructing the Los Angeles viaduct in the Mojave Desert, prospected in Death Valley, worked on the San Francisco waterfront and moved across the Southwest before heading east to Atlantic City, where he was employed as assistant steward at the Jackson Hotel.

All of this he packed in before he turned 24, moved back to Ohio and set his sights on a new profession. By now, Heffernan had decided to become a newspaperman.

In 1910, Heffernan secured his first job at the Youngstown Telegram, and then subsequently landed reporting duties with The Vindicator, The Ohio State Journal in Columbus and The Leader in Cleveland. From The Leader, Heffernan jumped at an opportunity to head overseas, where he free-lanced for newspapers in Europe, working for Pomeroy Burton, a former Youngstown resident who owned the Daily Mail in London.

When war broke out in 1914, Heffernan left Europe and returned to the United States, this time to pursue an entirely new venture: law. By his recollection, it took nearly 10 years of studies and saving while he worked in odd jobs and in the newspaper business to become trained as an attorney.

“I was trying to get an education, to get ahead in the world, and to escape from the very life that was tearing my body as if on a torture rack,” he recalled. By 1916, he had passed the bar exam in Columbus, returned to Youngstown and hung out his shingle.

Within a year, the United States had entered the war. Heffernan, now 31, found himself headed back to Europe, this time as an enlisted man in the American Expeditionary Forces. He recounted the anxiety traveling across the Atlantic, this time in a converted troop ship. “We understood that every German submarine in the Atlantic was hot on our trail. We expected to feel a torpedo every minute,” he said.

Initially, Heffernan was assigned to Army intelligence, but then joined the staff of Stars and Stripes as a war correspondent and served the duration of the war. His recollection of the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, during his 1924 address, depicts an exulted soldiery and a welcome end to more than four years of carnage that French and British troops endured. While witnessing French troops declaring “Vive l’Amerique!,” Heffernan reflected, “just to live that one moment was pay enough for all the suffering we went through.”

The Meuse-Argonne offensive broke the back of German resistance and led to the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918.

Heffernan spent a year after the war organizing the journalism program at American Expeditionary Forces University in Beaune, France, and on May 13, 1919, was honorably discharged from the Army. That same year, he was married to Beatrice Jones of Shropshire, England.

Upon returning to the states, Heffernan jumped squarely into Democratic Party politics and spent a year in Washington working on servicemen’s issues and at national party headquarters during the 1920 presidential campaign. Republican U.S. Sen. Warren G. Harding of Ohio defeated Ohio Gov. James Cox, a Democrat, in a landslide.

Heffernan returned to Youngstown with two goals in mind: to resume his law practice and to seek elective office.

Much of his political leverage was mustered from close friends such as Vic Dohaney, who was elected governor of Ohio in 1922. That same year, Heffernan opted to put his name forward for state central committeeman and Democratic Party Chairman of Mahoning County. His move, according to his unpublished memoir of Youngstown politics, upended the comfortable power brokers across the city and county.

“I suddenly defied the reigning political dynasty and ran for committeeman,” Heffernan, by now known as a progressive reformer, would write later. “To the surprise of the great leaders, I was at the head of the ticket. The cynical old warriors, however, decided that I must be squelched.”

After years of toiling in oil fields, steel mills, labor gangs, kitchens, and surviving the horror and carnage of the first world war, Heffernan became exposed to an entirely different sort of fight for which he was completely unprepared. He had decided to enter politics in the Mahoning Valley.

Part two of his amazing story will appear in tomorrow’s online edition.

Pictured above: Reporters for The Stars and Stripes were on the front lines with the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.