Future Uncertain for East Palestine Manufacturing Plants

EAST PALESTINE, Ohio – More than three months since a Norfolk Southern train derailed in the backyard of one of his three businesses, Edwin Wang sees little activity happening inside his manufacturing plants.

Wang, president and owner of CeramFab Inc., WYG Refractories and CeramSource Inc., has been unable to reopen his manufacturing businesses for more than a few hours since the Feb. 3 train derailment. At this point, he says the future of two of those businesses is in jeopardy. The third, CeramSource, an import wholesale business, is going to relocate.

Coming into 2023, Wang was ready to see his companies really begin to grow. CeramFab, the business he had started in the former Tubetech building on East Taggart Street, had successfully opened one manufacturing line in 2022 following several years of costly upgrades to the building, pandemic-related challenges and the search for trained labor. In 2022, CeramFab was employing about 15 people manufacturing high heat insulator fiber products for the ceramic and steel manufacturing industries.

Since 1999, Wang had operated CeramSource, which imports and distributes fiber products able to withstand temperatures of 2,300 to 2,600 degrees, in New Jersey, never losing money during that time. He previously imported the items from China, but after President Donald Trump-era tariffs cost him 25% to bring the products in from overseas – costs he was forced to pass on to the customers – and then the pandemic often left the products in limbo – floating off the coast – it became apparent to Wang it was time to begin making them himself in America. He personally drove through several cities and towns in West Virginia, Pennsylvania and Ohio, searching for the right location.

East Palestine was centrally located near many of his customers, and he set his sights on the former Tubetech building. At $500,000, it was the right price, but it required a lot of work – more than the purchase price – to bring the building up to date, including renovating a leaky roof and installing a drainage system behind the business.

But even then, Wang said the Norfolk Southern railroad, which runs right behind the building, was not the best neighbor. Junk plugging Sulphur Run on their property would flood the loading dock on the western end of Wang’s CeramFab building. Repeated requests for the railroad to clean up the situation brought Wang no satisfactory response, he said.

“We’re small potatoes. They’re a big company,” Wang said, noting his lawyer said he would need an engineer to prove the case.

So when he opened his first CeramFab manufacturing line in 2022, it was on the eastern side of the plant, away from the possible water concerns because his products cannot get wet. Companies in the steel industry were sending him orders, and the plant did $1.5 million in business in one year, running only one shift.

When 2023 started, CeramFab was training a workforce for a second shift. A second manufacturing line was starting, and the plant had room for six, eventually. Wang had every reason to believe all the money poured into setting up the equipment and remodeling the buildings of both CeramFab and WYG Refractories on James Street soon would be paying off.

WYG, which also employed about 15, makes MAG Carbon Bricks, especially for steel foundries. The materials also need to withstand high temperatures. Wang believes that business potentially could be more profitable than CeramFab down the road.

He was getting close to fulfilling a promise to create 45 to 50 jobs. But on Feb. 3, Wang said he was at home in Cranberry, Pa., ready for the weekend when he heard his wife, Kathy Wang, scream. She had just learned about the derailment in East Palestine. He pulled up the surveillance footage from CeramFab and could tell the business itself was not on fire, but there were derailed cars on fire behind it, and firefighters had brought trucks and equipment into his parking lot and through the plant to battle the blaze.

“That night I did not sleep,” Wang said. “But at that point, I didn’t think it was going to be a permanent operation shutdown.”

When he returned, he and his wife could smell a strong odor, although the doors were all open and a firefighting hose remained. He could see small, white granular material dispersed in the area. He and his wife suffered health problems when they returned and had to leave.

More than a week later, after getting the plants checked and being told by the inspectors it was safe for employees to return, the businesses began to reopen. But Wang said he almost immediately had to reclose because four employees came forward with symptoms. One had rashes all over him. They sent affected employees to the doctors and closed the doors again.

The railroad has offered him money, he said, first $20,000 and then $40,000 in inconvenience money, but he was nervous about their inability to provide him with any answers, and he refused to sign. He has since gotten a lawyer and filed a still-pending lawsuit, which has been added to a class action lawsuit.

Wang has given the Ohio EPA permission to use his property to clean up the railroad property. But he has a lot of questions, such as how long it will take and will the factory ever be safe for people to return. Vehicles performing the cleanup continue to use his parking lot and property.

As of May 12, the U.S. EPA reported 39,348 tons of solid waste has been shipped from the site, along with 16.7 million gallons of liquid waste. More contaminated soil is being stockpiled, covered overnight. The EPA has predicted work removing the soil under both tracks and from the site could be completed by the end of May.

Wang questions if the soil around the plant, which borders the site, will be safe when they are done.

‘We Lost Everything’

And while he waits for answers, many of those businesses he had contracts with, who were understanding at first, have looked elsewhere for the products they need.

“We already lost all of our customers’ trust of our ability to run production at this location,” Wang said. “I know all our customers, the businesses are hard to get, now all of the sudden are so easy to lose. They are all switching orders to our competitors.”

Even if things are all cleaned up this summer, Wang said the customers are already gone. And finding trained employees ready to return could still be tough.

“We’re losing money, We’re losing time. We’re losing labor. We’re losing our trained workers. It’s not like if you find somebody they can go straight to work. …We lost everything. We lost everything.”

He believes after investing so much money into his buildings, they may now be worth nothing, because no one wants to come to work there. All the brand-new equipment with 20- to 30-year life spans, which they installed, is useless to him right now, although he has had offers to buy the equipment, but not the buildings.

At CeramSource, the business Wang brought with him from New Jersey and is easier to relocate, there are pallets of materials both in its regular warehouse and throughout the WYG plant as he tries to stay in business. He is planning to relocate CeramSource to Beaver Falls next month, where he has signed a lease.

But finding the space for the other two manufacturing businesses and relocating the equipment would be too costly for him at this point, after investing and losing so much.

“I’m broke with these two plants,” Wang said. “I spent all the money, but I did not get a chance to get a return on the investment. I do not know what to do with these two plants.”

He has been offered interest free loans from the government, but he believes Norfolk Southern should be the one paying for the relocation of those businesses. It would be complicated to relocate and take more time to prepare another plant for the equipment. At 66, he wants to retire, but he had hoped to leave these businesses behind, a type of legacy.

“To set up a new business, it’s like planting seed,” Wang said. “Then you need to take care of it, water it, then it will grow, slowly, gradually. We did not get a chance to grow, so we lost the business already.”

Brown Meets With Farmers

CeramFab is only one of many businesses still struggling to find answers in East Palestine. U.S. Sen. Sherrod Brown met Monday with local farmers, who also continue to have questions and concerns about the safety of their crops and products after the derailment.

According to his office, Brown has secured a commitment from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to convene an economic empowerment forum to support the East Palestine community.

“This is the kind of community that’s so often forgotten or exploited by corporate America,” Brown said. “I’m here for the long haul. We’re still going to be here for months, for the next year, the next 10 years working to make sure residents get the support they need, and that includes every farmer in Columbiana County and the surrounding areas.”

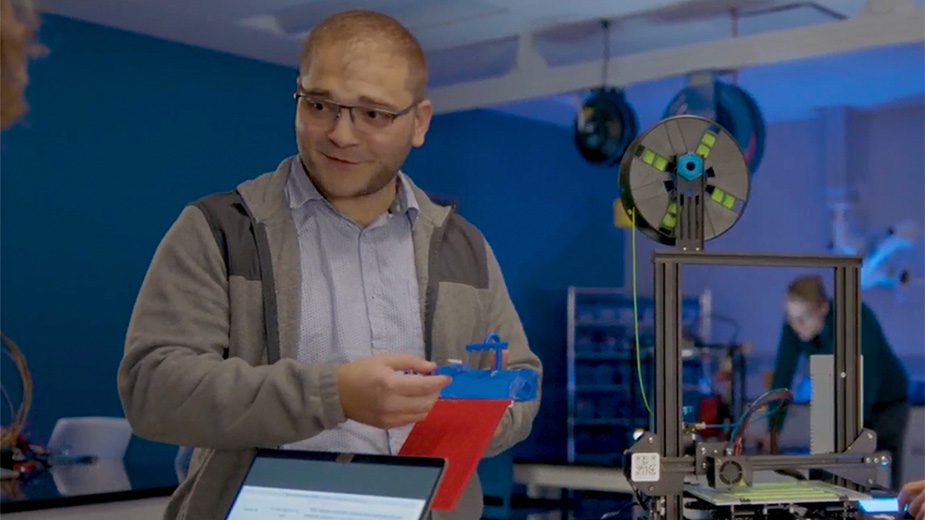

Pictured at top: Edwin Wang, president and owner of CeramFab Inc., WYG Refractories and CeramSource Inc., inside his WYG plant.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.