George Washington Returns to Ohio Country in 1770, this Time for Business

On Oct. 5, 1770, five years before the first shots of the War for American Independence would ignite a world conflict, George Washington set out with his personal physician and friend, Dr. James Craik, from Mount Vernon to the Ohio River.

The journey would bring Washington – for the first and only time – to what is today Columbiana County.

Washington, under the direction of the Royal Governor of Virginia, Gov. Norborne Berkeley, was charged with the task of evaluating 200,000 acres of land along the “Great Kahnaway,” or Kanawha River, a tributary of the Ohio about 250 miles downstream from where the Ohio forms in Pittsburgh.

The land along the Kanawha was to be parceled out to veterans of the Virginia militia – including Washington – who served during the French and Indian War, which had ended in 1763.

“Began a journey to the Ohio, in company with Dr. Craik, his servant, and two of mine, with a led horse and baggage,” Washington wrote in his Oct. 5 journal entry.

For “nine weeks and one day,” Washington, Craik, Capt. William Crawford (Washington’s land agent) and others traveled nearly 700 miles from Virginia to Ohio and back.

For Washington, now a 38-year-old gentleman planter of Virginia, the trip also presented an opportunity to renew acquaintances from his previous forays into the western lands. This wasn’t Washington’s first time in Ohio Country.

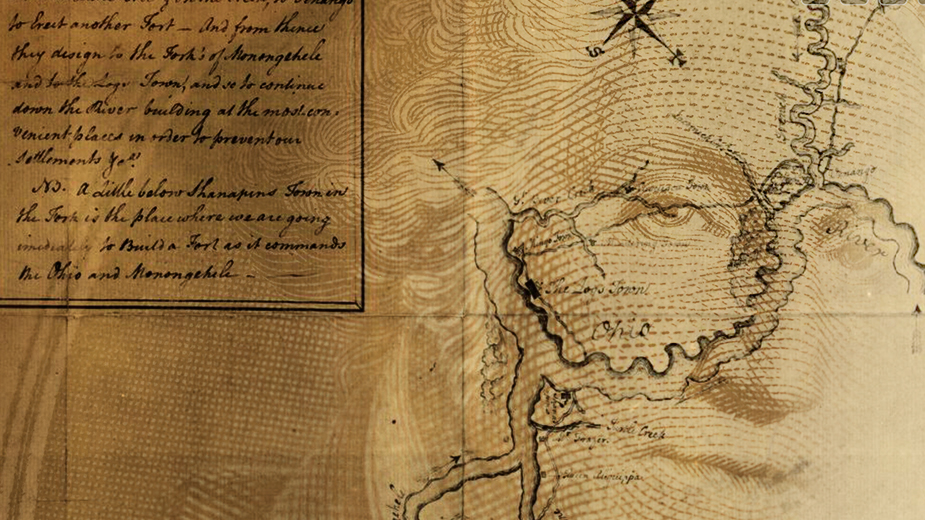

Seventeen years earlier, a 21-year-old Washington had volunteered to lead a diplomatic mission to Fort LeBoeuf, then a French-held garrison in modern-day Waterford in northwestern Pennsylvania. Gov. Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia dispatched Washington, surveyor Christopher Gist and four others to confirm reports of French intentions to control the Ohio Valley, land that Great Britain had also claimed.

Washington, Gist and several Native American allies – including the Seneca leaders Tanacharison, the “Half-King,” and Kiashuta – moved north through present-day Butler and Venango counties to LeBoeuf. Here, Washington learned of French designs to occupy the region and construct a string of fortifications from Presque Isle on Lake Erie to the forks of the Ohio at modern-day Pittsburgh.

After Dinwiddie received the information in January 1754, Great Britain approved a second expedition into the region to intercept French forces as they began occupation of the Ohio Valley at what was now deemed Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh). Washington was selected to lead the operation.

It did not go well. After a 15-minute skirmish between the French and Washington’s militia in southwestern Pennsylvania just south of Fort Duquesne resulted in the death of a senior French officer, Joseph Coulon de Jumonville, Washington took up defensive positions at Great Meadows. There, he constructed a crude, circular fort named Fort Necessity.

That short fight, Washington’s first military encounter, proved to be the opening salvo in what would become the French and Indian War – a world war for empire whose nucleus lay in the heart of the Ohio Valley.

The French interpreted Jumonville’s death as an “assassination” and responded with an assault on Fort Necessity. On July 3, 1754, Washington, now greatly outnumbered, surrendered his position and was forced to retreat to Virginia.

Washington’s defeat at Fort Necessity only emboldened Britain’s efforts to secure the Ohio Country. This time, though, it would be a full-scale offensive with British regular troops against the French under the command of British General Edward Braddock. Washington, now a Lieutenant Colonel in the Virginia Regiment, would serve as Braddock’s aide-de-camp.

That didn’t go well, either. On July 9, 1755, Braddock’s forces – then numbered 1,400 men – were met with a smaller French and Indian contingent that fought effectively enough to force the British into disarray. Braddock was killed in the battle, Washington had two horses shot out from underneath him, and the army retreated to Virginia.

Washington’s fourth excursion into the Ohio Valley occurred as part of Gen. John Forbe’s successful campaign to capture Fort Duquesne in November 1758. Shortly afterward, Washington resigned his commission in the Virginia militia. By 1763, the French surrendered its entire position in North America to the British, ceding Canada and all territories east of the Mississippi River.

By October 1770, George Washington was all business.

He had already achieved status as a wealthy member of the Virginia gentry and was looking to augment that position, even as tensions between the colonies and Great Britain intensified. Indeed, Washington’s latest excursion to the Ohio came just seven months after the Boston Massacre, a new low point in relations between the colonies and the Crown.

Washington’s fifth – and most extensive – journey to the Ohio proved less exciting than his previous but nonetheless important for future settlement and his own affairs in land speculation.

Washington’s journal leaves a detailed account of his Ohio trek spanning Oct. 5 through Dec. 1. Throughout his journey, the future president describes the geography along the Ohio River, its Native American inhabitants, the region’s wild game, natural resources such as coal, and the quality of potentially rich land.

By Oct. 13, the party had passed through Great Meadows, where Washington had met defeat in 1754. The following day, he joined up with his land agent, Crawford.

On Oct. 20, the group had reached Pittsburgh, left its horses behind and set off down the Ohio.

“We embarked in a large canoe, with sufficient store of provision and necessities,” Washington wrote. Also joining the voyage were interpreter Joseph Nicholson, Robert Bell, William Harrison, Charles Morgan, Daniel Rendon and one of Crawford’s sons. A Native American known as the Pheasant and a “young Indian warrior” manned a separate canoe. Col. George Croghan also accompanied the party for part of the trek.

Washington’s journal suggests that Croghan attempted to sell a tract of land he owned to Washington along Raccoon Creek, a small tributary of the Ohio that spills out near Monaca, Pa. “This tract he wants to sell, and offers it at five pounds sterling per hundred acres,” Washington wrote on Oct. 21, but demurred, “At present the unsettled state of this country renders any purchase dangerous.”

That same day, the party moved downriver another 10 miles to Little Beaver Creek, where Tanacharison – now dead – once maintained a hunting lodge.

“From Raccoon Creek to Little Beaver Creek appears to me to be a little short of ten miles; and about three miles below this we encamped,” he wrote on Oct. 21. George Washington had just entered what would become northeastern Ohio.

Washington’s encampment was probably positioned just north of East Liverpool. According to Washington, the men had earlier stashed a “barrel of biscuit in an island to lighten our canoe.”

Snow began to fall around midnight, Washington wrote on Oct. 22, “and continued pretty steadily, it was about half past seven when we left our encampment.”

As the canoes nosed their way along the banks of the Ohio, Washington observed “a long bottom of very good land about two or three miles” above the mouth of the Yellow Creek, a portion of which is in southeast Columbiana County. The land he describes is modern-day Wellsville (Ninety-one years later, on his way to his first inauguration, Abraham Lincoln made a stop here to briefly address supporters who had gathered outside his railcar).

That same day, the party navigated the Ohio past modern-day Steubenville and reached Mingo Town, today Mingo Junction. “This place contains about twenty cabins, and seventy inhabitants of the Six Nations (reference to the Six Nations of the Iroquois).” Some 60 of these comprised a war party headed west to fight the Catawbas.

Wary of potential hostilities in the region, Washington took pause after arriving at Mingo Town. “Upon our arrival at Mingo Town, we received disagreeable news of two traders being killed at a town called Grape-Vine Town, thirty-eight miles below this, which caused us to hesitate whether we should proceed, or wait for further intelligence.”

The following day, it was determined that a single trader drowned while fording a dangerous part of the Ohio. The other trader survived, and the expedition continued, Washington wrote.

By Oct. 28, Washington had made it as far south as Parkersburg, W.Va., where he encountered a hunting party under the leadership of the Seneca chief Kiashuta, whom Washington had met during his first trip to the Ohio Valley.

“In the person of Kiashuta I found an old acquaintance, he being one of the Indians that went with me to the French in 1753.” The Seneca chief treated Washington and his party well and insisted they spend the night, where they were treated to buffalo and other game.

By Oct. 31, the party had reached the Kanawha, where they spent the next five days surveying land along a 15-mile stretch. They returned to Mingo Town on Nov. 17.

Here, Washington swapped his canoes for horses, crossed the Ohio and set forth to Pittsburgh.

Although Washington was unable to ascertain the status of his own lands along the Ohio, he did treat the mission as a success. The voyage opened up his eyes to the potential of trade toward the West along the Ohio and the state of relations with Native Americans of the region and their appraisals of the land.

He would later write that he was “well-pleased with my journey, as it has been the means of my obtaining a knowledge of facts-coming at the temper & disposition of the Western inhabitants and making reflections thereon.”

Other matters, of course, would consume Washington over the next three decades. Yet the trip down the Ohio in 1770 never left him. According to his will, Washington, at the time of his death, owned 9,744 acres along the Ohio River, 23,341 acres along the Great Kanhawa, another 234 acres near Great Meadows, in addition to other lands in the Northwest Territory and Kentucky.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.