Heinz Center Showcases ‘Portraits of Pittsburgh’

By Pat Springer

PITTSBURGH — Is today’s selfie a portrait? Does it tell a story? Capture a fleeting moment? Is it stored forever on your phone? Is it shared with friends and family?

In a current exhibit at the Sen. John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh, Pa., more than 100 portraits of Americans with connections to western Pennsylvania define what a portrait is – and does. And they are not selfies.

The exhibit, “Smithsonian’s Portraits of Pittsburgh: Works from the National Portrait Gallery,” highlights how these individuals have impacted the history of the nation – and identifies questions about who is important in American culture.

In association with the Smithsonian Institution, it is one of the largest loans of artwork ever shared by The National Portrait Gallery. Created by Congress in 1962, the gallery, in its inception, stipulated that a portrait had to be a likeness of a person created with one of the fine arts: paintings, drawings, etchings and sculptures. Today, though, a wide range of mediums – photography, animation, video, posters, and installation art – are utilized.

The Heinz exhibition, housed in a structure built to replicate the National Portrait Gallery, is divided into five themes: Whose Impact Matters, On Stage and Screen, Restless Lives, The Face of Victory, and Industry and Innovation.

George Washington launches Whose Impact Matters. After his death, Washington became mythologized as the great American hero. With its stormy seas, cannons and flag, his portrait illustrates the grief of the country at the time and commemorates Washington as our founding father. During the French and Indian War, while working for the British, Washington was shot, fell into the Allegheny River and almost drowned. Later, in 1755, he witnessed Gen. Edward Braddock’s disastrous British defeat in the Battle of the Monongahela, which took place near the town that today carries the general’s name.

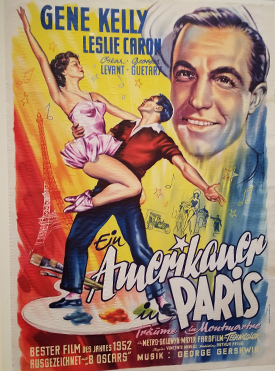

One name synonymous with Pittsburgh’s Stage and Screen is Gene Kelly. Kelly, who grew up in the city’s East Liberty section, left Pittsburgh in the late 1930s for a New York stage career. His lead in the 1940 production of “Pal Joey” led him to Hollywood where he starred in and choreographed many of the biggest musicals of the 1950s. Kelly is front and center in this West German poster from 1952 for “An American in Paris.” The film won six Academy Awards plus a special award for capturing dance on film. Behind the camera, Kelly pioneered new ways of filming and his athleticism and regular guy persona democratized dance.

During the 20th century, Pittsburgh was always more than a river town of smoke stacks and steel mills. As a transportation hub between New York and Chicago, Pittsburgh also served as a lively entertainment center. Vaudeville houses, nickelodeons, jazz clubs and ethnic neighborhoods flourished and nowhere was there a more vibrant cultural scene than in the Hill District.

Stage and screen legend Lena Horne, who began her career in New York, moved to Pittsburgh in 1936, when she married Pittsburgher Louis Jones. At the time, Horne’s father ran a hotel in the Hill District that served as a major hub for entertainers. Because Black people were not welcome in the segregated downtown hotels, the great jazz artists flocked to The Hill. For Horne, who rubbed elbows with greats Billy Eckstine and Billy Strayhorn, Pittsburgh became her training ground, leading to a signed MGM film contract in 1942. Her starring role, in 1943, in the all black version of Stormy Weather made her a star.

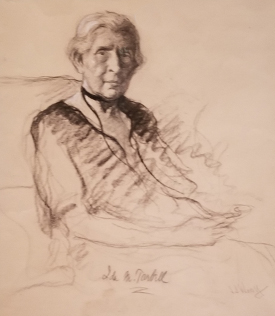

Inspiring talent is also seen in Restless Lives, a theme that showcases muckraking journalist Ida Tarbell. Tarbell’s landmark writings changed the face of American industry and pioneered investigative journalism. After watching John D. Rockefeller destroy independent oil producers such as her father who lived in Titusville, Pa., and put them out of business, Tarbell, in 1904, wrote a scathing bestseller, “The History of the Standard Oil Company.” The expose of John D. Rockefeller and his company was responsible for the breakup of the oil monopoly. Initially published between 1902 and 1904 as a series of articles in McClure’s magazine, the book is widely considered to be one of the most influential in the history of business.

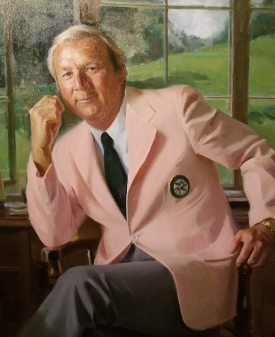

If Tarbell’s writings changed industry, Arnold Palmer’s swing revolutionized golf. His was the Face of Victory in the 1954 U.S. Amateur Golf Championship marking a new era in the sport. As the first of 92 wins for Palmer, the championship ushered in an era of new fans to the sport, big television ratings, and massive marketing partnerships. Growing up on the links of the Laurel Valley Country Club in Ligonier, Pa., Palmer built an “Arnie’s Army” of Pittsburghers, making him one of the most loved sports personalities in western Pennsylvania.

Palmer’s impact on sport followed George Westinghouse’s contributions to Industry and Innovation. Westinghouse helped modernize the transportation industry and electrify America.

He obtained his first patent at age 19 and moved to Pittsburgh in search of a manufacturer for his inventions. By the time he died in 1914, he had founded more than 90 companies and paved the way for electricity to power America’s future.

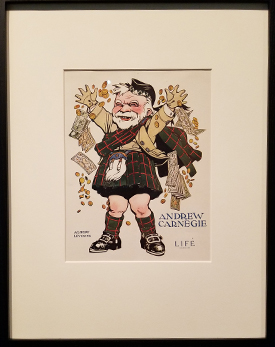

Andrew Carnegie transformed Pittsburgh into the Steel City and built institutions that millions of people still enjoy in western Pennsylvania and around the world. His was a classic rag to riches story. His first job as a teenager growing up on the north side (then Allegheny City) was as a telegraph messenger. He ended up as one of the richest men in the country. By the time he sold Carnegie Steel to JP Morgan in 1901, he had amassed more wealth than any person in America. After 1901, Carnegie gave away his fortune – to libraries, establishing foundations, education institutions and music halls.

The entire “Portraits of Pittsburgh” exhibit can be seen at the Heinz History Center daily from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Pictured at top: The Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.