Holocaust Survivor Tells of Horrors, Loneliness of Captivity

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – Holocaust survivor Art Gelbart spent much of his childhood in Nazi work and concentration camps before being liberated by American troops and moving to the United States to start a family.

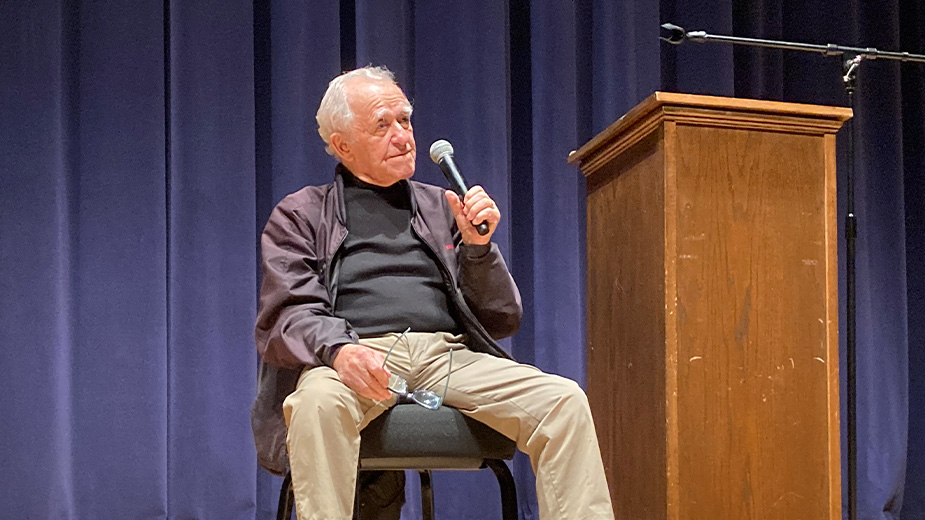

Gelbart, 94, spoke Thursday morning at Stambaugh Auditorium as part of the Jewish Community Relations Council of the Youngstown Area Jewish Federation’s Anti-hate and Educational Opportunities Initiative.

Students from several schools, including Austintown, McDonald, Boardman, Akiva Academy, Campbell Crestview and Sharpsville, Pa. were among the audience members.

“One of our most important missions at the federation is to educate about lessons of history, about bullying, about evil, about hatred,” said Bonnie Deutsch Burdman, executive of community relations/governmental affairs at the Youngstown Area Jewish Federation, in introducing the speaker.

These are confusing times, she said, referring to news of antisemitism.

“There is no more crucial time than now to confront the evil that surrounds us,” Burdman said.

While World War II may seem like ancient history to some, it isn’t, she said. There are still people alive who lived through it, including Gelbart.

“My name is Art Gelbart, and I am a Holocaust survivor,” he said as he began his presentation.

Gelbart was living in a small town in Poland with his parents and three sisters in 1939 when the Nazis invaded. He was 10, and his family was in the meat business and was doing pretty well.

“I remember it very vividly,” he said.

He and his family learned that day that German soldiers shot and killed two of Gelbart’s uncles, one brother each of his father and mother.

“With all of the memories right now behind us, we are still going through a second Holocaust,” Gelbart said. “Today, it’s hard for me to live with this.”

After the Nazis invaded, he and his family and other Jews living in that area had to report each morning to a central area to be counted by the soldiers.

After about a year, soldiers apprehended his father when he was trying to bring more food to the family. His father was sent to a concentration camp.

“We, of course, never saw him again,” Gelbart said.

He, his mother and sisters were sent to a ghetto with other Jewish families.The family lived in a couple of ghettos before Gelbart’s mother sent the children to a camp with plans to follow later.

She never made it. She was among people shot in the ghetto while hiding in a basement. The cries of a child hiding with them alerted the soldiers to their whereabouts.

Gelbart was working in one camp, and his sisters worked in another camp nearby. He worked, breaking up monuments from a cemetery and building roads with the stone.

He would work at a few camps during his captivity. At one point, Nazis were sorting the Jewish prisons into groups with one group headed for a concentration camp and the other group to stay and work. The calluses on Gelbart’s hands, showing that he was a hard worker, kept him in the work camp.

He didn’t know where his sisters were.

After about two years in the camp, it was taken over by Auschwitz guards and became a concentration camp.

“Things drastically changed,” Gelbart said.

Meals consisted of soup, which Gelbart suspects was made of grass and stones, and one slice of bread. He got in trouble at one point because one of the guards saw he had a piece of bread tucked in his belt.

“I was slapped in the face,” he said. “I lost one of my teeth, and I got 20 lashes.”

His punishment was considered mild as a Jewish guard was permitted to determine Gelbart’s penalty.

When the Jewish prisoners were punished, usually for minor infractions, the guards made the others watch. Gelbart recalled one time he watched as 10 people were hanged.

“At age 13 or 14, whatever I was at the time, that was probably the hardest thing for me to watch,” he said.

In January 1945, Russian troops closed in on the camp, and the guards moved the prisoners out.

“They took 4,000 of us on a death march,” he said.

They had to walk all day, stopping only at night to sleep in fields.

“The people that couldn’t make it were shot immediately right on the road,” he said. “I remember there was one German in particular, and he enjoyed shooting.”

Gelbart was among 1,800 prisoners who survived the two-week trek and made it to the next camp. Food was limited. Trucks drove by each day, tossing bread to those strong enough to get it.

It was a lonely existence, he said of his captivity.

“You didn’t really make friends,” he said. “You’d make a friend today, and tomorrow they would be gone.”

Prisoners were herded onto a train and sent to Buchenwald, where he was ultimately liberated. He and his sisters reunited and moved to the United States, first to New York City and then Cleveland.

Because Gelbart didn’t speak English, he enlisted in the U.S. Army to try to learn the language. He never returned to school, but he met his wife, Rose, also a Holocaust survivor, in Cleveland.

They have two adult sons and many grandchildren.

“For what the United States did for me, I will be forever thankful,” he said. “We were able to start to build a new life.”

Pictured at top: Art Gelbart speaks at Stambaugh Auditorium on Thursday.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.