Creating Opportunity with Training and Clay at HopeCat

SHARON, Pa. — Wearing medical scrubs and a white lab coat, Calette Robinson applies a blood pressure cuff to Martina Moore, her classmate at the Hope Center for Arts and Technology. The class of eight is in the center’s lab room practicing what they’ve learned.

Robinson is part of a 10-month medical assistant training program launched this year at the Sharon, Pennsylvania, center, known as HopeCAT. For the past four years, she’s worked as a certified nurse’s assistant, but wanted to further her career.

“This was an open door to another opportunity to be able to do that,” Robinson says.

As a working mother of three – ages 3, 6 and 8 – getting that education would have been “extremely difficult,” she says, “not to mention the amount of money that would’ve had to been paid.”

Calette Robinson (right) applies a blood pressure cuff to Martina Moore as part of her medical assistant training at HopeCAT.

Calette Robinson (right) applies a blood pressure cuff to Martina Moore as part of her medical assistant training at HopeCAT.

In 2016, tuition for a medical assistant program ranged from $2,500 to more than $16,000 depending on the school, according to BestMedicalDegrees.com. HopeCAT students don’t pay a dime.

“This is definitely an opportunity for everyone in the community,” Robinson says.

And it’s an opportunity to buttress the health care industry’s workforce. To receive its state license, HopeCAT had to show there were available jobs in the area, says Shawna Purnell, the program’s instructor.

“There were at least 30 jobs open within a 20-mile radius,” she says. Occupations include medical assistant, medical administrative assistant, phlebotomy specialist, “and some of the hospitals are hiring medical assistants as patient care technicians as well.”

Shawna Purnell is the instructor for HopeCAT’s medical assistant program.

During the first nine months of the program, students learn how to measure height and weight, take blood pressure and do basic lab work. They study anatomy physiology, medical terminology, dosage calculations and how to work with electronic health records, medical billing and coding. They also receive training in soft skills, such as how to write a resume and go for a job interview.

A one-month, full-time externship follows, says student services coordinator, Sarah Scott-Rossi. In addition to training, it’s an opportunity to find the job students want, she says.

“That’s their four weeks they have to network with people and put a vibe out about them in the medical community,” Scott-Rossi says. “We’re here to set people up for success.”

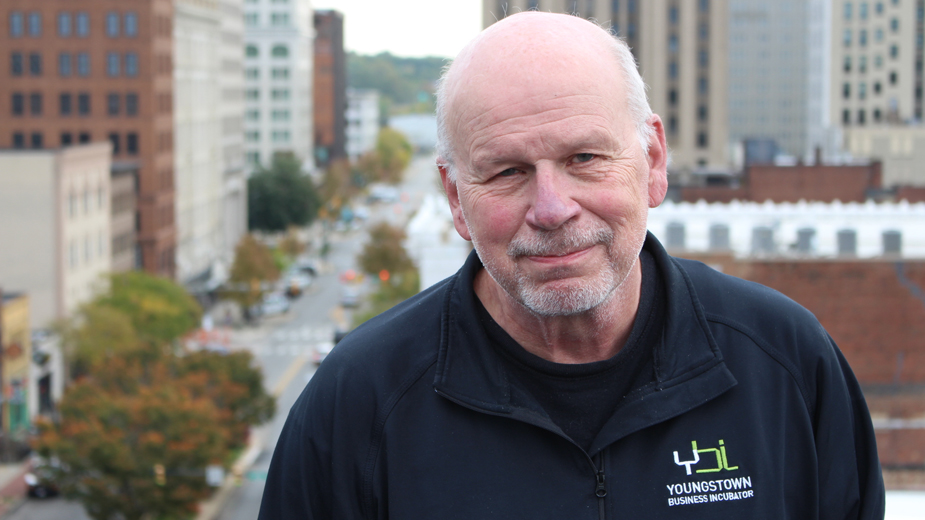

The medical assistant program is part of HopeCAT’s greater mission to transform lives and the community through education and art, says its executive director, Tom Roberts.

HopeCAT establishes the curriculum with its strategic partners – the Primary Health Network, Sharon Regional Medical Center and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

The center is primarily funded by a public-private partnership as well as some grants through the state, foundations, corporations and individuals, so programming is available at no cost to participants, Roberts says.

HopeCAT still has room to grow at its Anson Way location, says director Tom Roberts.

“This is truly a regional center and it’s a proven education model,” he says. “People ask us, ‘What’s the catch?’ The catch is you have to show up and you have to do the work.”

The 501(c)3 is still relatively young – having moved into the fully renovated former Sacred Heart School building at 115 Anson Way in September 2017 – but it’s part of a vision that began in the 1960s.

Manchester Bidwell Corp. in Pittsburgh is renowned for its market-relevant career training and youth arts programming. In 1968, founder Bill Strickland started a small ceramics program in the city’s Manchester district to provide students in struggling neighborhoods with the same mentorship he received from his art teacher, Frank Ross, at the former Oliver High School.

Through ceramics, Strickland gained an appreciation for art and education and was accepted into the University of Pittsburgh. After graduation, he founded the Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild and, in 1972, took over the struggling Bidwell Training Center that offers job training. Since then, Manchester Bidwell has expanded to 12 centers around the United States and one in Israel.

Since 2017, HopeCAT has offered after-school ceramics to students in ninth through 12th grades, a hallmark of Strickland’s organization. It began with a pilot program at Farrell Area High School and has since expanded to include high schools in Sharon and West Middlesex as well as Brookfield, Ohio. The goal is to serve Crawford, Mercer and Lawrence counties in Pennsylvania, and Mahoning and Trumbull counties in Ohio.

HopeCAT ceramics students (from left), Jordan Curtician, Bryasha Vaughn, Jada Williams, Amare Mason and Jazele Odem.

“We should be able to impact at least five counties from this location,” Roberts says.

HopeCAT can serve up to 64 students, and “the minute we add another arts curriculum, we can double that,” he says. Through visual arts, students realize that to celebrate success they must first learn a difficult process.

Their first efforts aren’t always successful and there are multiple opportunities for failure making mugs and bowls, which makes completing a project that much more of an achievement, Roberts says.

“And then we celebrate it,” he says.

Family, friends, community members and economic development leaders are invited to a showing where the art is available for sale. Students keep 90% of sale revenue, with 10% going to the school as a gallery fee, giving them entrepreneurship experience, “but also the pride in telling how they made what they made,” Roberts says.

It’s a lesson that Sara Cain, 17, took to heart. During one of her first classes, the Sharon High School senior couldn’t bring the clay up on the wheel. She was frustrated and wanted to quit, she says, but the instructor, Christian Kuharik, helped her along until she got it. Now she applies that lesson to life’s challenges.

“No matter how hard something gets, you should always go through and keep trying,” she says.

Cain was one of 12 students, all girls, to attend the center’s trip to Yellowstone National Park in June. There she met Aaris Williams, 17, a senior at Brookfield High School, who says the trip made her feel accepted, more so than school.

“It was like a little community because we were all different personalities coming from different families and backgrounds,” she says. “Just connecting and loving each other, accepting each other, helping each other, living with each other – it was a beautiful thing.”

Sara Cain (left) and Aaris Williams met through HopeCAT and were among 12 students who attended this year’s trip to Yellowstone National Park.

Bringing kids together who otherwise wouldn’t have met allows them to learn from each other, Scott-Rossi says. Students come from various economic and family backgrounds, including single-parent homes and foster homes, she says. After dinner one evening, the campers engaged in a conversation about economics, religion and politics “and everybody stayed calm,” she says.

“They had different opinions and they could talk about them,” Scott-Rossi says. “We’re putting people together who are different from one another, and they’re thriving.”

Additionally, the program helps keep kids in school, she says. HopeCAT monitors attendance and if students attend regularly, they may participate in the program.

For Williams, the art program motivates her to attend college, which is something she wasn’t considering before enrolling.

“When I came here, I felt like I had purpose and I could do something more with myself,” she says. “It was a push in the right direction that I really needed.”

HopeCAT mentors students for post-secondary education, whether it’s college or a trade school, Scott-Rossi says. The student lounge features a map of Pennsylvania and Ohio with schools identified by stickers that are printed with each school’s location, cost to attend, and required grade point average and SAT scores.

“I can show them what they have to work toward,” she says. Scott-Rossi also makes available information about trade schools and skilled labor apprenticeships.

Bringing together students from different backgrounds is a big part of HopeCAT’s mission, says its students services coordinator, Sarah Scott-Rossi.

Roberts looks to expand arts education into digital arts, he says. The staff is researching programs and speaking with regional employers about in-demand skills, from computer numerical control, or CNC, machining, to 3D printing.

“We’d be queuing these students up with real world technical skills,” HopeCAT’s director says.

HopeCAT just completed another phase of its $4 million renovation of the school’s second floor with a digital arts space and 10,000-square-feet of “vanilla box” classroom space. When complete, there will be 10 classrooms for expanded curriculum or leasing opportunities, he says.

HopeCAT is on target to remain within its annual budget of $750,000 to $1 million, Roberts says, and within the next year employment will likely increase to 10 full- and part-time, up from seven. As for the future, he wants to fill every room in the building.

“We are uniquely positioned to collaborate with high schools, colleges, trade schools, public schools and employers in a way that no other nonprofit can and does,” he says. “We’re working very hard to break generational poverty one person, one family at a time.”

How You Can Help

Community members can make a positive impact on the Hope Center for Art and Technology by making a donation or volunteering time to the organization’s programs.

Donations made online can be given in single or monthly payments by visiting HopeCAT.org and clicking on Donate. Donors can also contact HopeCAT’s executive director, Tom Roberts, by calling 724 308 5135 and discussing their wishes.

“If you choose to invest in this education model, we want to make sure that we carefully handle your investment in the future,” Roberts says.

Interested volunteers can contact HopeCAT to discuss their interest in helping. HopeCAT currently has volunteers who help in the ceramics studio, work during special events, or manage the front desk.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.