Mahoning River Slowly Scrubs Its Contaminants

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – It reads like the recipe for a lethal toxic soup: 400,000 pounds per day of suspended solids, 70,000 pounds per day of oil and grease, 9,000 pounds per day of ammonia-nitrogen, 500 pounds a day of cyanide, 600 pounds a day of phenols (carbon acids), and 800 pounds per day of zinc.

Even more harrowing is that these figures represent the average daily discharge of contaminants into the Mahoning River from the nine major steel plants that hugged its banks circa 1977, according to a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region V waste allocation study published that year.

“The lower Mahoning River remains today as one of the most severely polluted streams in the nation,” the study concluded, referring to a 40-mile segment of the 113-mile river dominated by steel interests stretching from Warren to New Castle, Pennsylvania. Once those mills fell silent during the late 1970s and 1980s, the environmental damage left behind was staggering, leaving a cleanup price tag initially estimated at $150 million.

But something remarkable has happened in the 40 years since that scathing appraisal by the EPA. Over the last several decades, the river has been slowly cleaning itself, turning what once was a chemical cesspool into a partially navigable and recreational haven for canoers, kayakers and wildlife enthusiasts.

“We were told when we were young to never go near that river,” recalls Lowellville Mayor Jim Iudiciani. The village was once home to a steel mill owned by the Sharon Steel Corp. and is downriver from the bulk of the industrial contamination once fed from Youngstown and Warren’s mills.

What would have been unthinkable even 10 or 15 years ago is today likely, as Iudiciani maps out the future of Lowellville with the river as the focal point of his village. “It could serve as a catalyst,” he says. “We feel that we have an opportunity with the river going through our little town.”

The community today is embracing the river as a potential economic and recreational engine, Iudiciani says, and a new comprehensive plan for the village incorporates the river as a central feature from which the community could engender a better quality of life. Among the plans are a riverfront park with a canoe livery, he says, noting that additional river property would be ideal for residential or recreational development.

The first phase of this effort should start sometime this year as work begins on the removal of the Lowellville dam. Removal of this dam and eight others along the Mahoning River are the most critical and costly components to cleaning the waterway. The Lowellville project could cost about $2.3 million.

“By the end of this year, the dam should be out,” Iudiciani says.

Removal of these dams is integral to the cleanup because it restores a free-flowing river that would reinvigorate the natural habitat, inviting fish, avian and other aquatic species back to the waterway.

Absent the dams, the river is able to essentially scrub itself clean of contaminated sediment over time, says Joann Esenwein, director of planning for Eastgate Regional Council of Governments. The agency is working with eight communities – Warren, Niles, McDonald, Girard, Youngstown, Campbell, Struthers and Lowellville – to fund dam removal along the Mahoning.

“Lowellville is funded and should begin this year, Esenwein says, and Struthers is now funded.” Most of the dredging, she notes, would be done behind the dams and other pockets of “hot” areas before the dams are physically removed.

It’s a much better situation than 20 years ago, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers estimated a cost of about $150 million to clean the river, Esenwein says. That project, however, called for dredging the entire river from Levittsburg to Lowellville. Now that most of the dredging would be limited to the areas where dams are present, the cleanup costs should be dramatically less.

The Mahoning River snakes through current and former industrial sites along its path, such as the Vallourec complex that straddles Youngstown and Girard.

The Mahoning River snakes through current and former industrial sites along its path, such as the Vallourec complex that straddles Youngstown and Girard.

“There’s still sediment – nothing really hazardous – but it’s not quite to the point where the habitat is back,” Esenwein says. “The Mahoning is much cleaner today than it was when the Army Corps of Engineers did its study,” she affirms.

That study, released more than 20 years after the scathing EPA report, still found the Mahoning to be chock full of contaminants. The study made reference to an Ohio Department of Health Human Health Advisory in effect at the time that warned people to refrain from contact with the sediment of the river and fish in it. The Army Corps report also raised concerns over the presence of “pollutant-tolerant fish, dominated by carp and catfish species, with external physical anomalies.”

Indeed, according to the Army Corps, the decades of industrial discharge along the Mahoning “has resulted in the degradation of the aquatic ecosystem and has become a threat to public health.”

You’d be hard pressed to convince Moneen McBride of this today as she gazes at water flowing at a rapid clip along an upper portion of the river that bends through Levittsburg in Trumbull County. It’s a mostly rural area of the river that at some points are studded with houses overlooking the rushing water, and a portion that has for years accommodated fishing, canoeing and kayaking.

“We’ve gone down the river several times,” McBride says. “Our first trip was last year.”

McBride and her husband operate Burning River Adventures, a business in Cuyahoga Falls that provides kayak and canoe rentals to trekkers on the upper Cuyahoga River.

This year the company expanded its footprint to include the Mahoning River as a new launch and tourist attraction, citing the resurgence of the river as a focus of recreational development in northeastern Ohio.

Moneen McBride and her husband opened Mahoning River Adventures on Memorial Day in Levittsburg.

Moneen McBride and her husband opened Mahoning River Adventures on Memorial Day in Levittsburg.

“Both rivers are similar in that they’re former industrial rivers, and were not really used for recreation,” McBride says of the Cuyahoga and Mahoning. “The Mahoning has excellent potential because 28 miles of it is a designated water trail by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources.”

McBride’s new business – Mahoning River Adventures – launched Memorial Day at Canoe City Park in Levittsburg, part of the Trumbull County Metroparks system. The company provides kayak rentals and livery service to those interested in experiencing firsthand navigation of the Mahoning River.

“A lot of the Mahoning is today maintained and beautiful,” she says, “and the missing piece was a business like ours that offers a livery service.”

The company plans to offer two treks down the Mahoning, one a roughly four-mile trip that originates at Thomas Swift Park and another that spans 11 miles beginning at Rotary Park below the Newton Falls dam. Both trips end at Canoe City in Levittsburg, where patrons park their cars. A livery service transports kayakers to their launch points.

“In this section of the river, you’re in forested areas,” observes Zachary Svette, operations director for Trumbull County Metroparks. “There are waterfowl, otters, bald eagles. Blue herons are prevalent here.”

Svette says the river has gradually become healthier since the 1980s, which is why the Metroparks expanded access through parks such as Canoe City. “It’s a big part why Mahoning River Adventures is here,” he says.

The overall health of the river has improved drastically since the studies during the mid-1990s, says Bill Zawiski, supervisor of the water quality group at the Ohio EPA. “If you had gone into the Mahoning 25 or 30 years ago, it would have been a warm stream and very toxic for fish,” he says. “That’s not the case today.”

During the 19th century, the Mahoning was explored extensively, Zawiski notes, and was a waterway that caught the attention of some of the most prominent naturalists of the country. Jared P. Kirtland, then among the leading zoologists in the country that extensively studied fish species across Ohio, identified several types indigenous to the Mahoning River. These specimens were sent to the Smithsonian for further study and are catalogued there today.

“Industrialization changed all of that,” Zawiski says.

In 1994, when the Ohio EPA conducted its last water quality study, it assessed 29 sections of the river and just two met the agency water quality benchmarks. Three of those goals were partially met. The rest received a failing grade.

In 2013, another water quality study was conducted in which 25 sections were examined. Of those 25 sections, 11 of those met all of the quality standards and 12 others were partially met. Just two sections of the river received failing marks.

“Visually, it’s a much different river than it was 25 years ago,” Zawiski says. “There are no consistent oil sheens. It’s canoed in places.”

“There’s a sense of community ownership and pride in the river,” says Kurt Princic, Northeast District division chief of the Ohio EPA. “It was considered an afterthought 30 years ago. Now it’s viewed as a major asset and part of the community.”

These efforts continue, as grassroots groups such as Friends of the Mahoning River and community development agencies work to bring more awareness to the benefits of the Mahoning River.

James Dignan, president and CEO of the Youngstown/Warren Regional Chamber, says he and others plan to travel to Washington, D.C., June 20 and 21 to lobby officials for more federal funding to help restore the Mahoning.

“This area was the economic engine that drove everything here in Ohio during the early 20th century and we were left with a mess,” Dignan says. “This country owes the Mahoning Valley a clean river.”

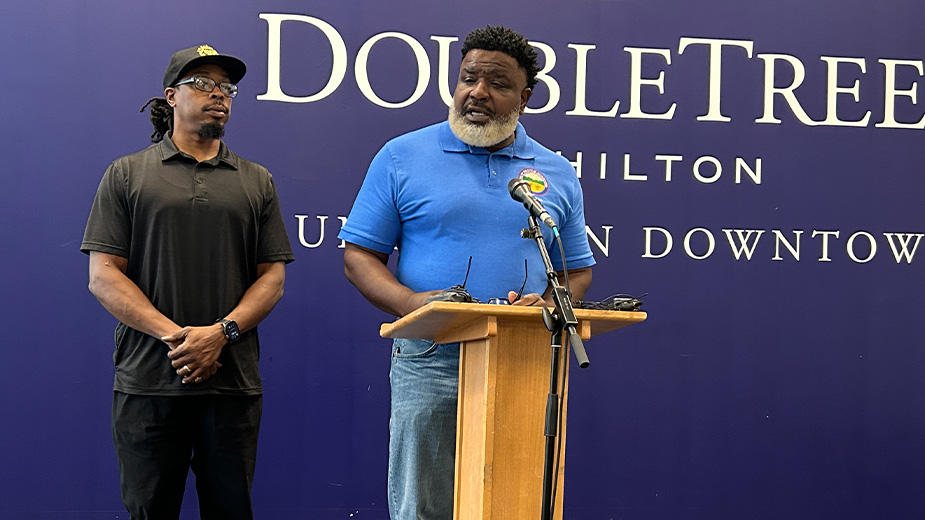

Pictured: Absent the dams, the river is able to scrub itself, says Joann Esenwein of the Eastgate Regional Council.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.