Learn the Mystery of the Ohio River Petroglyphs

By Dan O’Brien

EAST LIVERPOOL, Ohio — Chaussegros de Lery awoke on the morning of April 3, 1755, to find his encampment crusted with snow on what was to be a very cold day. About 10 a.m. the French officer and his party moved across the Ohio Valley, navigating the terrain and streams as they made their way toward Fort Duquesne, then a French garrison at modern-day Pittsburgh.

Around 3 p.m., de Lery recorded in his journal that the party crossed a river with which he was already familiar – he had encountered it 16 years earlier during a 1739 expedition under the command of Charles Le Moyne to Louisiana against the Chickasaw.

“The river we left is called Riviere au Portrait, because at the mouth where it flows into the Belle Riviere, there are many signs and figures of men and animals chiseled on the rocks,” he wrote.

De Lery’s account presents one of the earliest written references to Native American carvings on a large, flat sandstone expanse at the confluence of the Ohio (Belle) River and Little Beaver Creek, which de Lery in 1739 named Riviere au Portrait, or “pictures in the river.”

The site of these carvings, just across the modern-day Ohio state line near East Liverpool into Pennsylvania, evidently commanded enough attention to earn a prominent display on Lewis Evans’ 1755 map of North America. A spot along the Ohio River on that map labels boldly the location of “Antique Sculptures” – a physical landmark by which traders and surveyors could now make their way through the Ohio country.

For centuries, hundreds of these Native American carvings – or petroglyphs – stretched for about 10 miles along the Ohio River from Midland, Pa., through Wellsville, Ohio, to the Yellow Creek. The origin or date of the petroglyphs remains unknown and will likely never be determined.

During the 1920s, a series of dams and locks was constructed along the Ohio, causing water levels along this part of the river to rise. By the 1950s, “super” dams were added on the Ohio and the river rose even higher. Today, the petroglyphs are inundated under about 15 feet of water.

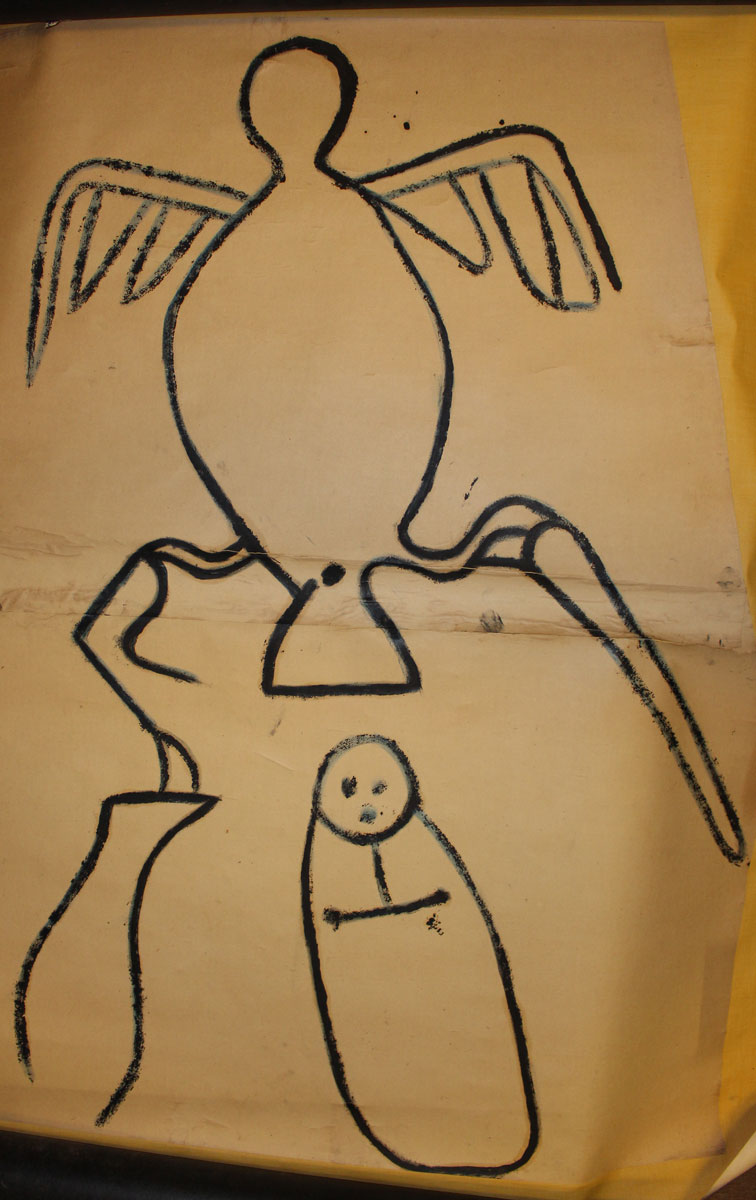

Not all was lost. On three occasions in 1940, 1948 and 1958, water levels along this part of the Ohio receded to a point where these images were exposed for the first time since the 1920s. For weeks, thousands of onlookers visited the stone outcrop near Smith’s Ferry, where the Little Beaver spills into the Ohio. The petroglyphs haven’t been viewed since.

Yet many imprints of these markings survive. While some early photographs of the petroglyphs exist, the vast majority of the carvings are preserved thanks to the work of Harold Barth, an East Liverpool resident who in 1908 spent a year transferring the carvings onto large tracts of paper.

“If it wasn’t for him, we wouldn’t have this wonderful collection,” says Susan Weaver, director of the Museum of Ceramics in East Liverpool. Today, all of Barth’s images are rolled and stored in large tubes at the museum, each one labeled with the month and year it was made. “He collected everything, and it’s amazing how many of those things have become very useful and have documented our history.”

According to the East Liverpool Historical Society, Barth used an unorthodox method in his efforts to preserve these carvings. In 1908, he directed a crew charged with clearing the rocks of silt and debris. Then, the team poured printers ink and liquid dryer into the outline of each figure carved into the rocks, after which a large sheet of absorbent paper was pressed over the petroglyph. The result was the creation of more than 200 imprints that today are stored for posterity and academic interest at the Museum of Ceramics.

The imprints were made at sites at Midland, Brown’s Island, Babb’s Island, Smiths Ferry and Wellsville. And these images provide a snapshot of an entirely different world.

Captured forever are imprints of simple carvings of thunderbirds, turtles, snakes, human figures, curious symbols and various other animals and people, lending insight into Native American culture in the Ohio Valley region. The precise date and significance of the petroglyphs remain uncertain, but scholars have determined they were carved sometime between 1200 and 1750 CE.

Among these scholars was James L. Swauger, who during the 1950s was associate director of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh. Swauger accompanied Barth on an excursion to examine the carvings in 1940 and his 1974 book, “Rock Art of the Upper Ohio Valley,” relies heavily on Barth’s collection.

“There’s probably more mystery than there is history about these,” says Timothy Brookes, an East Liverpool attorney who is also president of the East Liverpool Historical Society. “They were remarkable even in the 1700s when white explorers and settlers started to come to this area.”

French trappers, English surveyors and infantry from both sides during the French and Indian War all passed through this region.

In October 1770, George Washington undertook an expedition along the Ohio where he made reference to Little Beaver Creek and most likely took notice of the markings.

“From Raccoon Creek to Little Beaver Creek appears to me to be little short of 10 miles, and about three miles below this we encamped; after hiding a barrel of biscuit on an island [probably Babb’s Island] to lighten our canoe,” Washington wrote in his journal Oct. 21.

These petroglyphs continued to command interest at the highest levels in the early republic’s government. A series of drawings by mineralogist Benjamin Henfrey depicting the petroglyphs at Wellsville, for example, was forwarded to then Vice President Thomas Jefferson on Dec. 31, 1798, and are among his papers.

Barth’s collection is especially vast, intriguing and hasn’t been opened in years. Several of the transfers examined by The Business Journal are quite large – about five to six feet in length. These particular reliefs are heavy inked images of winged creatures, animals and what appears to be a faceless, feather-adorned Native American figure.

“The carvings are somewhat representative, but more abstract than anything else,” Brookes says.

By the turn of the 20th century, the petroglyphs had emerged as a tourist attraction, he says. But as the East Liverpool pottery industry and other nearby manufacturing operations expanded, so too did the need for natural resources such as the Ohio River.

“One way they could make the river a year-round operation was to dam the river,” Brookes says. “When the dams went in, the low-lying areas were covered.”

Before the carvings were inundated, people visited the sites – especially Smith’s Ferry and downstream along the riverbanks into Ohio, where acres of these carvings existed, Brookes says. “I had family members telling me they would picnic there because of the stone carvings,” he says.

Brookes recollects that one of his friends was driving to work from East Liverpool to Midland, Pa., along the river in 1958 when he noticed the river had retreated and the carvings were nicely exposed. “He called in sick, got his shovel and a camera and took pictures of all the petroglyphs he could,” he says.

Exactly who created these petroglyphs remains a matter for debate, Brookes says, since an exact date cannot be fixed on when they were carved. Swauger suggests in his 1974 study that the drawings could be the work of Monongahela Man, or “proto-Shawnees.” Others contend they were created later, perhaps by 17th- and 18th-century inhabitants who included Mingo, Delaware, Shawnee and Wyandot peoples. While archeologists have advanced that the carvings represent some form of communication or perhaps spiritual significance, deciphering their precise meaning remains elusive.

“People have been speculating about these petroglyphs for a couple hundred years now,” Brookes says. While it’s unfortunate that the carvings are submerged and cannot be accessed or viewed, the attorney muses it might be for the best. “If they weren’t covered up with water, I fear they might have been vandalized into extinction. I think they were probably doomed one way or another.”

Pictured above: Susan Weaver, director of the Museum of Ceramics, displays one of the ink imprints of petroglyphs owned by the museum.

“Flashback” is sponsored by Hickey Metal Fabrication, based in Salem.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.