NFL Helmet Challenge Puts Safety First

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — When the NFL and its partners descend on Youngstown for the kickoff symposium of the league’s Helmet Challenge on Nov. 13 through 15, they will take the latest steps in a decades-long drive to make the country’s most popular sport safer.

While the league began collecting data on player injuries in the 1980s, it took some time to figure out what exactly to do with it, says Dr. John York, co-owner of the San Francisco 49ers and a member of the NFL’s Health and Safety Committee. Over time, the information morphed into new rules and policies.

One of the biggest steps came with the creation of concussion protocols and the rating system for helmets, which has seen the safest helmets all created within the past five years. Now, York and the NFL are looking to additive manufacturing to aid in creating the next generation of helmets that are even safer.

“We’ve had concerns about football throughout history, all the way back to Teddy Roosevelt questioning if the sport should be banned and the implementation of the forward pass,” York says. “We want to build a truly better helmet, not just 1% or 2% better. We want 10%, 15%, 25% better.”

In recent years, measures were taken to increase safety. The NFL implemented a safety scale for helmets, rating them either red, yellow or green. This season, all helmets with a red rating were banned and players had to find new models to use.

“That affected less than 30 players. A couple kicked and screamed, but the others found a helmet,” York says.

Because the Health and Safety Committee includes a representative from the NFL Players Association, York says adoption of 3D-printed helmets will likely not be an issue.

“There really should not be a big difference if we’re both working to find ways to make the game safer. It falls outside the negotiations, where there is contention,” York says. “Riddell, Schutt, Under Armour and a few others all said players wouldn’t change their helmets. That’s true if you don’t have data. If you share the data with your players, they will pay attention.”

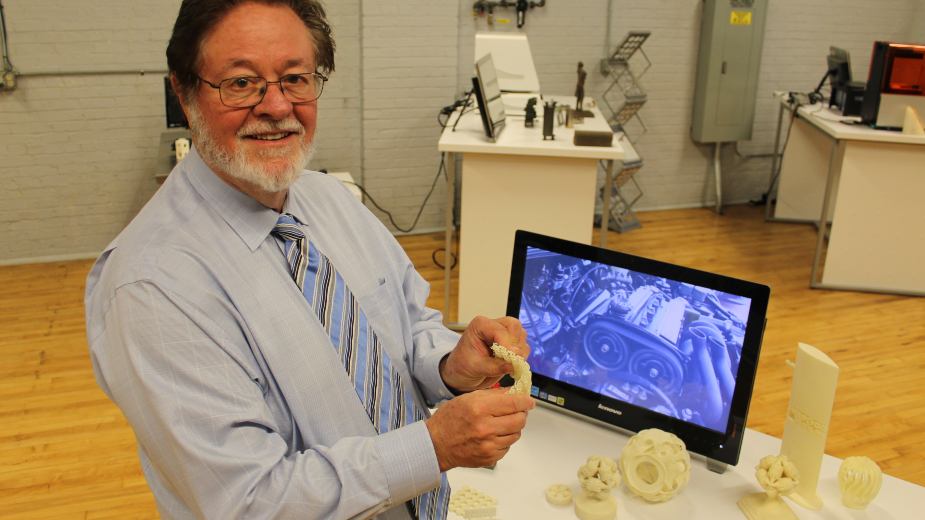

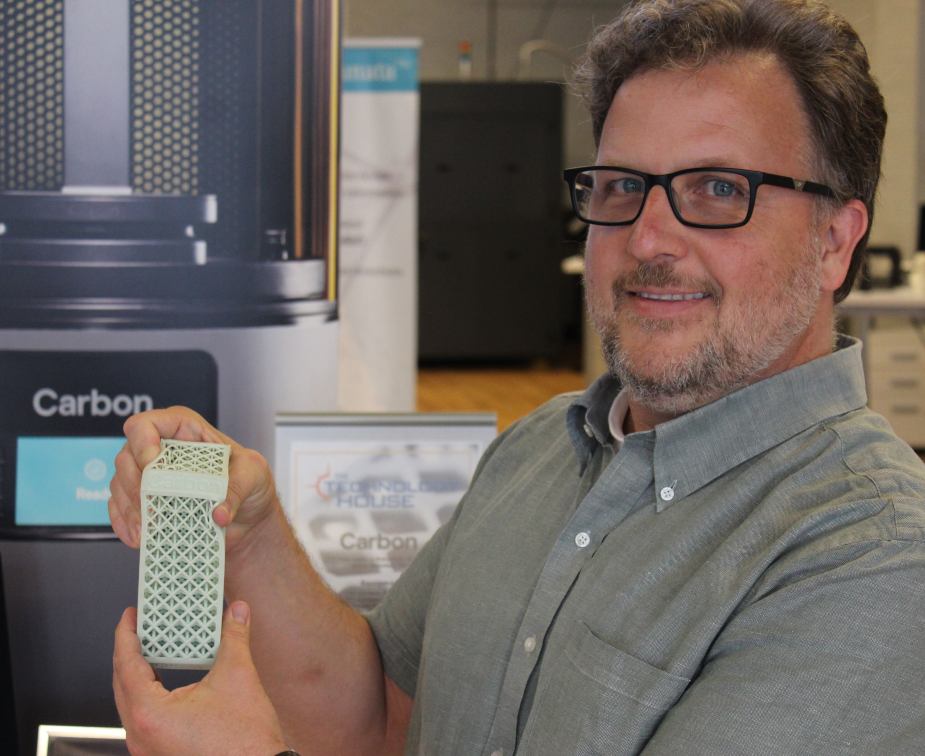

Among those looking for advanced technologies that can be incorporated into helmets is Youngstown State University electrical engineering professor Eric MacDonald, who points to a lattice material showcased at America Makes, which will host the Helmet Challenge symposium. The block of 3D-printed material, made by California-based Carbon Inc., is soft and squishy at one end and inflexible on the other.

“It’s just as durable as anything you’d use in traditional polymer or elastimer manufacturing,” says the Friedman Chair in Manufacturing at YSU. “But it’s something you can’t do with a mold. You can, across 3D space, change the features’ sizes to help protect players.”

If such a material were used, players’ heads can be scanned to come up with precise measurements and a lattice could be custom-printed to fill in the space between the helmet shell and head. Then, as researchers learn more about how to best protect the head during a hit – York says studies have shown hits to the top of the forehead, earhole and back of the head are most likely to result in concussions – the lattice can be configured to be soft or stiff as needed.

The Helmet Challenge will award up to $2 million in grants to develop prototype 3D-printed helmets, as well as a $1 million award to further develop a 3D-printed helmet. The grants will be awarded in March, with the deadline for submissions May 2021. At press time, more than 250 had registered for the symposium.

“It’s getting everyone together to understand the problems in the helmets and what additive manufacturing can do, as well as other advanced technologies, to make them better. It’s the chance to get everyone together and brainstorming,” says Ashley Totin, project engineer at America Makes, which is hosting the symposium.

For the additive manufacturing institute, founded in 2012, the arrival of the NFL will bring with it the chance to show off what’s going on among its 230 member organizations, which range from academic institutions like Youngstown State University to businesses to government agencies.

“The public usually thinks of 3D printing as making little trinkets or things they don’t understand. To get something everyone understands in the NFL is amazing for the area,” Totin says. “They’ve heard of 3D printing but may not understand it. Now they can see what’s happening in their backyard.”

But it isn’t just helmets the NFL is interested in improving. It’s total safety, York says.

“We need to look at rules, enforcement and protective equipment, whether it’s helmets, shoulder pads, shoes, the playing surface. All of those things come into play,” the 49ers co-owner says.

Already, Carbon is working with Adidas to create lattices for the shoe company’s FutureTech line. And the NFL, separate from the Helmet Challenge, has launched its Engineering Roadmap, a $60 million effort that supports research to create safer equipment.

So far, the league has awarded grants totaling more than $1.6 million for projects including padding on the outside of helmets developed by VyaTek Sports, an experimental playing surface created by FieldTurf and a padding designed to be 3D printed created by Cardiff University.

While MacDonald’s work at YSU isn’t directly focused on helmets – “I’m not in biomechanics. I’m an electrical engineer,” he says – his knowledge of additive manufacturing and using sensors in 3D-printed parts could bring about safety improvements. After meeting with York in mid-October, MacDonald got to work on a prototype mouthguard embedded with a sensor that measures movement, acceleration and other metrics.

“Potentially, if this is in the mouth, it could be used to check temperature. You could do a lot of stuff,” he says. “Within the context of an athlete, there are so many things you can measure and you put all of this within the structure and at the same time protect their head.”

Whereas measuring the impact of hits has previously been done by measuring the helmet, that doesn’t always provide a good set of information, MacDonald explains.

“The whole point of a helmet is to absorb energy and attenuate the hit. The hope is it accelerates more than your head. This [mouthguard] is mechanically coupled to your skull very strongly. If you still have excessive acceleration, this will detect that,” he says. “What you really want to know is how the brain’s moving inside the skull, but there’s no way to really measure that, so this is pretty close.”

At the Helmet Challenge symposium, MacDonald hopes to connect with helmet manufacturers to further his prototype.

“I’m trying to come up with some cool things that captures people’s imagination,” he says from his office at YSU. “The league wants a proposal in January for the teams [that will work together on a helmet prototype]. It has nothing to do with sensors. If it’s in there, it’s icing on the cake. But they’re very specific about the cake; it has to stand up to some rigorous mechanical impact.”

That’s exactly the sort of thing that undergirds the symposium, America Makes’ Totin says: the exchange of ideas, whether they’re about helmets or not.

“This is a huge opportunity to help the NFL solve this problem and there are so many people locally and across the United States wanting to be part of this and utilize an emerging technology,” she says.

And, York adds, bringing groups together to work on the helmets made through additive manufacturing rather than each company working in its own silo could help mitigate some of the cost, both for them and players.

“If you get a better helmet and all manufacturers, either by themselves or in relationship with an additive manufacturing company, the price will either stabilize or come down,” he says, noting that current helmets can range upward of $500 each. “That’s what will make it more accessible to universities and colleges and high schools.”

Pictured above: Dr. John York shows a flexible plastic made with 3D printing, which could be a new material used in helmets.

RELATED Story with video:

With NFL Backing, Future of Helmets Starts Here

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.