Quaker City Has a Rich and Moral History

SALEM, Ohio — Could you have traveled to Salem in 1850, your first take would be a quiet, country town not unlike other small communities in this part of Ohio. Beneath that surface, however, boiled a radical sentiment on the most divisive issue of the day, and perhaps in the history of this country.

Here, practically the entire community embraced the cause of abolition and was not in the least reticent about bringing a swift end to slavery. A decade later that issue fractured the union as the United States fell into civil war.

By comparison with other cities in the Midwest during the mid-19th century, Salem was as progressive a town as could be found. It was in Salem, for example, that the first women’s rights convention in Ohio was held, and said to be the first gathering of its kind in the United States organized and developed entirely by women.

Salem’s devotion to the abolitionist movement isn’t unusual given its philosophical and religious foundations, says David Stratton, director of the Salem Historical Society. “Quakers primarily were the ones that originally settled here,” he says.

The Quakers, or the Society of Friends, are a religious sect that emerged from a Christian movement during the mid-17th century in England. Their tenets included opposition to slavery, civil disobedience, opposition to alcohol, and nonviolence.

“Quakers had an influence on building and forming the town until about 1815,” Stratton says, noting other faith-based groups followed.

Once Ohio was granted statehood in 1803, migrants from the East moved westward and the village of Salem was established in 1806. Two men, Zadock Street and John Straughan, used their property to form the original section of the town.

Inside the city history society are thousands of artifacts, archives and books that tell the story of Salem. What stands out in much of the collection is the community’s intense dedication to abolition and equality.

“The western headquarters of the Anti-Slavery Society was here in Salem,” Stratton relates, as he points toward a far wall on which hangs a framed copy of the Anti-Slavery Bugle, an abolitionist newspaper published in the town between 1845 and 1861. The paper’s motto beneath its flag reads, “No Union with Slaveholders.”

Indeed, during the 19th century, the town provided an enclave for abolitionist activity and debate. Frequent speakers and visitors included William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth. It was during an address Aug. 23, 1853, at Salem’s Old Town Hall that Douglass implored his audience to “Agitate, agitate,” against the institution of slavery.

Another occasion in 1852 led to a now-famous encounter between Douglass and Truth, both former slaves and fervent abolitionists. In his speech, Douglass denounced the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

Truth stood to ask, “Frederick, is God gone?”

Today, on Truth’s tombstone is the inscription, “Is God Dead?” based on that 1852 meeting in Salem. During this period, Truth worked closely with Marius Robinson, then the editor of the Anti-Slavery Bugle, and toured the country as an advocate for women’s rights and the end of slavery.

“She would promote The Bugle, and stayed here for some time,” Stratton says of Truth.

Because the town was an openly avowed abolitionist community, Stratton says that houses often acted as safe havens for fugitive slaves. Some houses – the Daniel Howell Hise Home at 1100 Franklin Ave., for example – were known to harbor slaves fleeing the Upper South.

Much of this is documented in Hise’s diary, Stratton relates.

Other sites in the city along Lincoln Avenue are also believed to have served as safe houses for slaves. Often they are referred to collectively as stations on the Underground Railroad. All are part of a guided tour the history society gives to bring to life Salem’s abolitionist past.

“There was a lot of moving into Salem, and then moving out of Salem,” Stratton says of escaped slaves.

Former slaves such as Strotter Brown found a home in Salem after the Civil War, Stratton says. Once freed, Brown moved north and settled in Columbiana County, just outside the village.

“He made his name known as ‘The Basket Maker,’” Stratton relates. The history society has several of Brown’s baskets that date from this period, all of which have his signature notch on the handle. The notch was the trademark Brown used to indicate the piece met his high standards of quality.

When he died – around the age of 100 – the community chipped in and purchased a formal headstone. “His baskets are quite collectible today,” Stratton says, each possibly worth hundreds of dollars.

Salem’s abolitionist heritage was celebrated during the city’s centennial in 1906. On the third day, deemed “Anti-Slavery Day,” Salem hosted Booker T. Washington, the former slave who had risen to become the most prominent black leader in the United States. Just two weeks after the event, Washington wrote to the city’s organizers:

“My Dear Sirs – I cannot express to you in words how deeply grateful I am to the people of Salem for devoting a day to the celebration of the abolition movement. So far as I know, Salem is the only city in the country which has ever had such a celebration.”

Stratton points out that Salem was also home to the first women’s rights convention in the United States that was organized specifically by women. Earlier efforts – the Seneca Falls Conference in New York and the National Women’s Rights Conference in Massachusetts – had the help of men. The convention was held April 19, 1850, the first in Ohio, and was planned, conducted and organized entirely by women.

Other famous men and women stopped in Salem during the 19th century. On Jan. 8, 1872, Mark Twain presented a lecture as part of his “Roughing It” series in Salem’s Concert Hall. That day, in a letter written in Salem to his wife, Olivia, he lamented that he was tired of the lecture circuit and longed to be back in Connecticut. “Well, slowly, this lecturing penance drags toward an end,” he wrote.

Twain’s lack of enthusiasm for his audience and the every-night drudgery of speaking engagements must have shown. On Jan. 10, a reviewer in the Salem Republican opined that the lecture “as a whole did not meet expectations,” although it did contain “some passages of fine description and word painting.”

Ultimately, the Republican reviewer wrote, “No one could tell when he told the truth or when he was indulging in fiction, and when he was half through, his hearers had lost confidence in his sayings, and did not expect to be told anything on which they could rely.”

As the 20th century dawned, the industrial age lured new manufacturers to Salem along with innovative businessmen.

Delmar Davis, an electrical engineer at the local power plant who also operated the city trolley system, built Salem’s first automobile. “It was an electric car,” Stratton says, and made its first appearance on Salem’s streets July 31, 1900.

The history society has on display the carriage seat and control handle of that first auto. “This is all we have left of it,” he smiles.

Salem’s industrial sector grew during the early 20th century, as companies such as Mullins Manufacturing Corp. produced metal stampings and in the 1940s introduced its Youngstown Kitchen product line – an array of metal cabinets, sinks, dishwashers, refrigerators, tables and countertops for the post-World War II consumer culture.

Salem Labels, another company, gained prominence from its ability to affix images onto curved metal surfaces, such as aluminum cans, notes Janice Lesher, curator of Salem Historical Society’s collection. “Spam was one of their clients,” she says, along with other popular national brands.

The history society’s collection consists of material and archives in three buildings. The archives are housed in the Dale Shaffer Research Library – named for the Salem librarian who devoted 28 books mostly to Salem history – while another building on the campus is devoted to culture, sports and entertainment. A third building – named “Freedom Hall,” is a replica of Salem’s Liberty Hall, the meeting place for the Western Anti-Slavery Society.

Among the more renowned Salem residents is Alan Freed, the pioneering radio disc jockey credited for popularizing the term “rock ’n’ roll,” and who organized what is considered the first rock concert in 1952, in Cleveland. An exhibit with memorabilia from the 1950s and Freed’s life – he was a 1940 graduate of Salem High School – is on display.

Salem’s history is a reflection of this country’s story over the last 200-plus years, Stratton relates. During the Republic’s most trying period, the town wasn’t afraid to tackle the most divisive political issue of the era. It championed the cause of women’s rights 70 years before universal suffrage was granted in 1920.

While Salem enjoyed the benefits of innovation and industry through the 1960s, it also witnessed and bore the brunt of industrial decline during the latter part of the century, Stratton says. It’s the goal of the history society to preserve all of these stories.

“It’s important to recognize the significance Salem people have had and enjoyed,” Stratton says, “and the progress that we’ve made.”

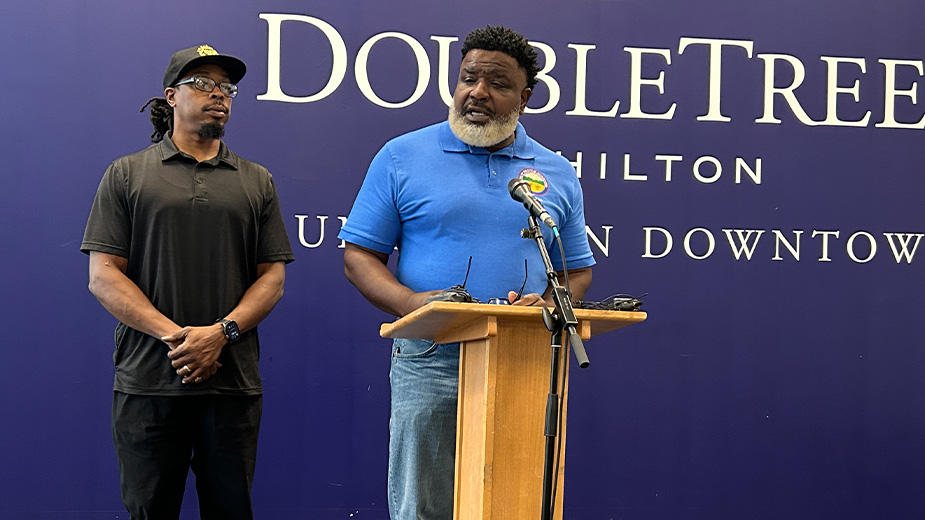

Pictured: Janice Lesher is curator of the Salem Historical Society, David Stratton its director.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.