Researchers Discuss Data from Testing in East Palestine

EAST PALESTINE, Ohio – Jess Conard has been looking for answers for her and her family after the Norfolk Southern train derailment in the village.

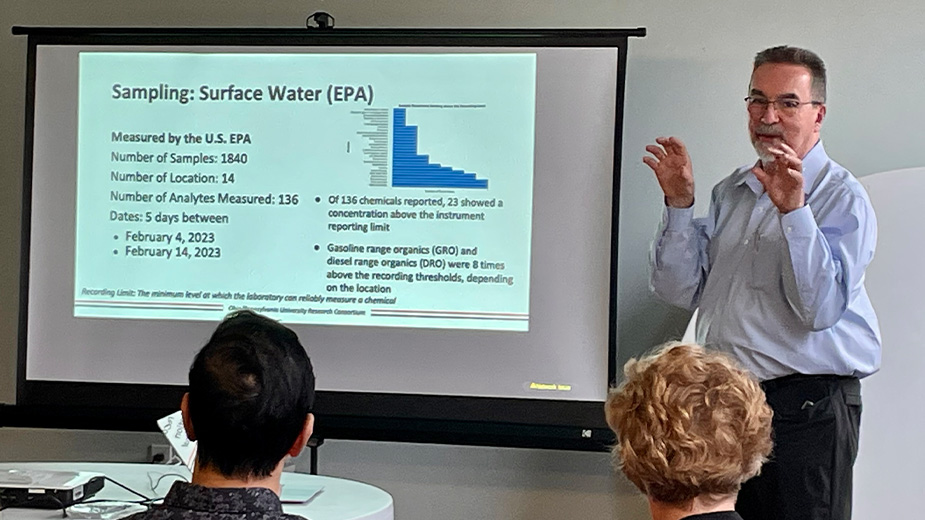

She was hoping to find some at an event Wednesday at The Way Station, hosted by the OH/PA University Research Consortium, which includes researchers from Case Western Reserve University, The Ohio State University, Kent State University and the University of Pittsburgh. Those researchers went over some of the data they had received, including that collected by the Environmental Protection Agency, to take an objective, scientific and nonpolitical look at it.

Conard was among residents in attendance who expressed concern about the lack of long-term air testing and the lack of inclusion of children, the elderly, pregnant women and other vulnerable people in the early health research.

“I’m grateful for the academic work that’s happening in East Palestine,” Conard said. “But I think many of us, from the beginning, have been looking for real time advice and real time validation, and that science is not going to help me decide what to do next.”

Conard said she feels the symptoms people are having are no longer acute health symptoms.

“It feels like we continue to feel gaslit about the causes of our acute health symptoms, which truly now are chronic exposures,” Conard said. “At the bare minimum, even if some of the rashes are stress-related because this is a stressful situation, the stress itself came from this disaster and should be acknowledged and validated as such. But I will say, never in my life as a medical professional have I heard of a 4-year-old being diagnosed with asthma due to stress or an elderly person being diagnosed with chemical burns due to stress. Yet these are things we are being told.”

Members of the OH/PA University Research Consortium have been reviewing the data collected from the train derailment and shared their reviews of the outdoor air tests, water tests, plant tests and human health surveys. Another meeting is planned to go over their review of the soil testing, as well.

Fredrick R. Schumacher, an associate professor in the department of population and quantitative health sciences at the Case Western Reserve University school of medicine, said the idea behind the review was to ensure residents knew someone besides those collecting the publicly available data – which included the federal and Ohio EPA and other groups – were looking over it and interpreting it. He looked at the health assessments conducted and wished there was additional data to look at.

“It’s not just more – it’s making sure it’s a focused assessment,” Schumacher said.

Schumacher admitted some frustration with the lack of response in the weeks and months following the derailment, noting first responders were on the ground quickly to put out the fire, but he questioned who was responsible for overseeing the response long-term. Despite all the calls for health care response in the wake of the Sept. 11 terrorism attack, Schumacher said there still is really no playbook for how to respond to natural or man-made disasters.

He said he would like to see a registry of everyone who was at the scene on the night of the derailment, including who was in a home within a block, a few blocks or miles, and for how long were they exposed to the burning chemicals. Did they stay or were they evacuated?

More than 732 people in Ohio and nearly 300 in Pennsylvania participated in a voluntary health assessment, the CDC’s ACE Survey, conducted in the weeks following the derailment, which logged each person’s exposure, health symptoms and mental health concerns within a 2-mile radius. However, Schumacher believes data on residents is sparse, and more should have been encouraged to participate. He hopes people will get involved in some of the additional health studies.

“This has to be an opportunity where everyone needs to get into the race, even if it is just in the short-term,” Schumacher said.

Following the presentation, another resident questioned why no one took his blood and urine around the time of the derailment. Some of the seven studies recently funded through the National Institute of Environmental Health will now do that. Through the University of Pittsburgh, researchers are looking at urine and blood samples, along with water, soil and air. Another University of Pennsylvania study will look at how the disaster will impact people, crops and livestock over time.

More information on getting involved in the University of Pittsburgh studies can be found here.

A study through Case Western Reserve University will look at genotoxicity, which measures the impact of DNA from chemical exposure and how it can increase the risk of certain diseases in the future. The information on participating in this study can be found HERE.

Darcy Freedman, director of the Mary Ann Swetland Center for Environmental Health at Case Western Reserve University, said it was clear from the beginning that there was no one university or organization in the immediate area that could answer all the questions people would have after the derailment. And while there are limitations about what can be determined as a cause or effect on someone’s health, she urges people to continue with the research and help get answers, which will be something that will happen over time.

Schumacher said though people had acute exposures early on, at this point they have become chronic exposures for those still having health concerns. He also said it is not known what happens to people when these chemicals are combined together and set on fire.

Schumacher was not the only scientific expert at the meeting to question what was missing from the data collected early on. Timothy Ciesielski, a research scientist at Case Western Reserve University, went over the air testing. He talked about the thousands of air samples that were taken, including more than 15,000 by the EPA between Feb. 4, 2023, and Jan. 16, 2024. The 156,018 tests conducted checked for 67 chemicals. And of those tests, 12% found one of 46 chemicals at levels high enough for detection. Vinyl chloride, the known carcinogen being carried by five tanker cars and the chemical responsible for the decision for the controlled vent and burn on Feb. 6, was among them, but only in the beginning. The detection of vinyl chloride was not above levels of concern and dissipated over time.

However, Ciesielski also noted there was a second time vinyl chloride was detected, in November 2023. That “blip” as it was described was a concern for some residents in attendance, who wanted to know where it came from and how.

Conard, who has become the Appalachia director of Beyond Plastics, an environmental group concerned about the effects of plastics, said the unexplained spike in vinyl chloride detected nine months following the derailment makes her question what was happening that caused it. Conard said she was told by Mark Durno, U.S. EPA response coordinator, that it could have been caused by work being done at the derailment site.

“It’s really scary that they’ve made up their own rules about when we should be notified and when we shouldn’t,” Conard said. “Like the rule was when there was a sustained level at or above 20 parts per billion, that’s when the public would be notified. But they only test for a 24-hour period. … I feel like we have a right to know, and are there any other blips? They’re not even testing air quality anymore. So if the remediation continues, then there is the possibility there could be additional (chemical) emissions during the process.”

Ciesielski pointed to another smaller air test they also analyzed, where air samples were taken by Carnegie Mellon and Texas A&M researchers while they drove around the derailment site for two days in February 2023. While that test detected several peaks of chemicals, including acrolein, it did not report how high the acrolein was, and it was unable to name which other chemicals it found, Ciesielski said.

Ciesielski said if more tests came back positive over a longer period of time, he believes there would be more health concerns.

Roger French, a professor at the Case School of Engineering, went over the surface water testing and sentinel wells that will continue to be tested. He said much of what was found in surface water would be readily expected from the diesel carried by the trains and five locations where vinyl chloride was found.

French said there were some inconsistencies in water testing, and some testing was sparse.

Haley Shoemaker of The Ohio State University Extension went over the results from chemical testing of plant tissues in the area, which took months in Ohio State’s labs. Shoemaker said plants do not readily draw semi-volatile organic compounds from groundwater and soil, if any were there. They were mostly looking for soot and other byproducts from the burning railcars.

The experts who spoke at the meeting asked residents to inform them about questions they still have following the presentation and what kinds of testing and scientific information they want in the future.

What would Conard like to see in the future?

While President Joe Biden and others who have come to East Palestine since the derailment have said the village will not be known for the derailment, but for its resiliency, Conard wants the village to be known for even more.

“I would like to see that taken a step further and be the town that changed train policy and the town that changed the way we respond to chemical disasters and the town that implemented a health care policy for anyone within a 20-mile radius of a chemical plant, or chemical disaster or a vinyl chloride emission,” Conard said. “These are the changes that could have national and global impact, and it would make our story our own.”

Pictured at top: Fredrick R. Schumacher, an associate professor in the department of population and quantitative health sciences at the Case Western Reserve University school of medicine, and Timothy Ciesielski, a research scientist at Case Western Reserve University.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.